Hatpin Panic: How Hat Pins Upended Gender Politics in the 20th Century

Early 20th century woman with hat pins in her hair. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

March 4, 2019 ~ By Shari Rose

Updated January 8, 2022

One hundred years ago, hat pins were at the center of a fiery debate concerning the rights of women to exist in the same public spaces as men. This is the Hatpin Panic.

- Gender Politics Transform During Height of Hat Pins

- Hat Pins as Stabbing Weapons Against Mashers

- Some React to Hatpin Stabbings with Support

- Lawmakers Experience Hysteria During Hatpin Panic

- How the Hatpin Panic Ended

As women gained more independence and autonomy outside the home at the turn of the 20th century, public debate reached a fever pitch over the use of hat pins. With the newfound use of the hat pin as a weapon, women suddenly found themselves with the ability to defend themselves against predatory men, called mashers, on the street and on public transportation. For the first time, women posed a physical threat to men through using hat pins. But it wouldn’t be long before male lawmakers sought to limit the power these women now wielded in public spaces during the Hatpin Panic.

As a result, women held protests, organized marches and shared impassioned speeches in an effort to rebuke these imposed limits on the use of hat pins and their ability to keep themselves safe outside the home. Sound familiar? While women today fight for the right to bring predators to justice through the #MeToo movement, the source of the 1900s woman’s power while out in public lay with the humble hat pin.

Large Hat Pins Gain Popularity in Ladies’ Fashion

Toward the end of the 19th century, women’s hats gradually grew in size as fashion trends dictated larger and larger women’s headwear. To represent one’s social status, a prominent woman may purchase a hat with jewelry or feathers of rare birds atop it. In fact, the bird populations of some species of local birds, such as the egret, were decimated across the U.S. as demand for these ornate hats reached unprecedented levels.

Fashionable ladies wearing large hats in the early 20th century. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

With these large, elaborate hats becoming all the rage in women’s fashion, the ability to keep one’s hat and hair in place during the day became increasingly important. The answer to the modern woman’s predicament in this era? Beautiful and sharp hat pins.

Hat pins were on average 8 inches long, though some could reach a foot in length. Hat pins helped secure the wearer’s hat to her head by interweaving with her hair. They were initially crafted with silver, but soon hat pins were created with brass, glass, and porcelain. High-end pins were adorned with decorations made of amber, coral, ivory, enamel, pearl, gold, and other materials. Gorgeous and intricate designs of natural phenomena, such as birds or insects, could be found on more expensive hat pins, while working classes usually adorned their pins with buttons or beads.

Gender Politics Transform During Height of Hat Pins

As ladies’ large hat pins became more and more commonplace at the turn of the 20th century, social norms were changing significantly. For the first time, jobs outside the home became available to young women in cities, such as piecemeal work in factories. As a result, women were walking on the street alone for the first time, commuting to work or spending their hard-earned wages in restaurants or shops in the city.

With this newfound female independence in the public sphere, dating norms began to shift dramatically as well, further setting the stage for the Hatpin Panic. Traditionally, a potential suitor would court a young woman in the home, under the watchful eye of her parents. However, those times were quickly going the way of the horse-drawn carriage as young ladies enjoyed greater freedom to venture outside the home, go where they wanted in the city, and date whomever they pleased.

Unfortunately, this push toward greater rights and freedoms for women also came with a higher degree of danger, namely in the form of the “masher.”

The Threat of Mashers

Mashers were predatory men who targeted single, young women on public transportation, on the street, and in other public spaces. These mashers would harass, make unwanted advances, and assault young women as they traveled. Some mashers dressed in the finest clothes to try and give the appearance of a well-to-do, and therefore, trustworthy, man. If this situation rings some bells, it’s because these mashers are not unlike that brand of creep you see today on the subway or bus with a plastic smile and a fake chivalrous tone to win over an unsuspecting woman’s trust.

Men pose in front of a streetcar in Denver, CO. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

In other words, mashers are those everyday creeps that prey on single women on the street, on public transportation, or just about anywhere in town. Every woman reading this now knows exactly the kind of threat that these turn-of-the-century women were facing then, too.

But unlike the mace or pepper spray we may conceal in our bags to protect ourselves today, those resourceful ladies found a weapon that arguably is just as effective: large, sharp pins hidden beneath their hats.

- More stories: What Daughters of Bilitis Achieved for Lesbian Rights in the U.S.

- More stories: How Constance Kopp Became First Female Sheriff’s Deputy

- More stories: How Jennifer Morey Survived Brutal Knife Attack & Rebuilt Her Life

Hat Pins as Stabbing Weapons Against Mashers During the Hatpin Panic

For the first time, women posed a threat of physical violence to mashers in the public sphere, armed with their hat pins.

Early 1900s hat pin for a woman’s hat. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

When two men attempted to rob a streetcar in Chicago in 1898, one woman did not stand by and watch the crime unfold. Sadie Williams was one of five passengers in this streetcar when the men started to attack the conductor. The streetcar’s three male passengers remained seated and did not help.

When it became clear the conductor was going to lose this fight, Williams jumped into action. She pulled out her hat pin and stabbed the robber closest to her. He yelled in pain and turned to attack her instead. Williams stabbed him again, and the man ran out of the streetcar. She then sank her hat pin into the face of the second robber, stabbing him in the cheek. He passed out.

When the fight was over, Willams asked the conductor if he was alright, but quickly passed out herself. She came back to her senses and was escorted home by authorities.

In 1901, four young ladies aged 17 to 20 were attacked on their way to Williamsport, PA. Two men stopped them as they were crossing alone on a bridge and began assaulting two of the girls. In the struggle, one of the girls exclaimed, “Use your hat pins!” They all stabbed viciously, and the mashers fled.

In 1903, a woman named Rosa Wilson was riding in a New York City streetcar when a man entered the vehicle and stood directly in front of her. He then started to nudge her several times with his leg, and didn’t take his eyes off her. Having enough, Wilson reached into her large hat and retrieved a 9-inch pin. When this masher touched her again, she stabbed him in the leg multiple times. He shrieked in pain from the sharp weapon and quickly exited the streetcar.

- More stories: Masako Katsura: Japanese Billiards Player Who Broke Gender Barrier

- More stories: America Has The Highest Maternal Mortality Rate Among Western Nations

- More stories: When Columbia Expelled Robert Burke for Anti-Nazi Protests in 1936

In an interview that helped further fuel a growing Hatpin Panic, Wilson said she intended to treat every masher she meets the same way, saying she had “begun a hatpin war on mashers.”

That same year, Leoti Blaker was visiting New York City from Kansas. While riding in a public stagecoach, a stranger made unwanted advances toward her. When this masher wrapped his arm around her lower back, Blaker had enough. She pulled out her hat pin and stabbed the man’s arm.

According to witnesses, he screamed and ran off at the next stop. While being interviewed by the New York World, Blaker said, “If New York women will tolerate mashing, Kansas girls will not.”

Some React to Hatpin Stabbings with Support

The popularity of hat pins was of relative disinterest to the male-dominated society until the stabbings against mashers entered the public consciousness. As stories of young women defending themselves against male assailants were pouring in as the Hatpin Panic began heating up, some powerful voices expressed support for the use of hat pins to help keep women safe.

A woman poses in a late 19th century photo wearing a large hat with flowers. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The New York Tribune published an instructional story about how to use hat pins as defensive weapons that was reprinted in several other newspapers across the U.S. It argued that hat pins were better for weapons for women than guns. Ultimately it sought to answer the question: “What, then, can be provided for her that will be formidable to a foe, yet absolutely safe, so far as she is concerned, and ever ready at hand, whether wanted to use or not?”

This article answers, in part:

“There are times in every woman’s life when a suspicious-looking character arrives on the scene and a voice whispers to the woman, ‘Beware of him.’ While most women would shrink from pulling out a revolver, it is an innocent act to put the hand to the hat and draw out one of her stiletto-like hatpins.”

Additionally, when the Hatpin Panic was heating up, some judges supported a woman’s right to carry a hat pin as a weapon against attacks on the street. In 1902, Justice Robertson made this precise argument when he ruled in favor of a young St. Louis woman whose hat pin stabbing brought the case to court. When speaking to her, Robertson said, “I think you were justified in using the hat pin on him. If you had stabbed him a few times more, I believe you would have done right.”

Despite the public showing of support in some circles, a fire was brewing among male lawmakers to put an end to hatpin stabbings. However, their interest was not in stopping mashers from attacking women, but rather stopping women from defending themselves with hat pins.

- More stories: When Martha Mitchell Was Right About Watergate

- More stories: Lucy Hicks Anderson: Black Transgender Pioneer of the 1940s

- More stories: Marshall Sherman’s Capture of Virginia Battle Flag at Gettysburg

Male Lawmakers Experience Hysteria as Hatpin Panic Takes Hold

Despite women’s use of hat pins to defend against violence instead of instagiting it, lawmakers and city officials across the U.S. immediately set to task to outlaw hat pins. During what is now known as the Hatpin Panic, public debate quickly shifted from discussing threats of violence against women to the threat that hat pins posed to men.

Before this time, men had never really faced a reality in which women could physically defend themselves and even cause harm to them on the street. The widespread use of hatpins created a new set of circumstances in which U.S. society had never seen before. It’s no coincidence that the discourse concerning a hatpin ban hit a feverptich as American women gained the most social and political freedoms they’d ever had since the country began, and the men in charge began to make their talking points.

Artistic rendition of what the 1910s all-male committee on hat pins probably looked like during the Hatpin Panic. This definitely wasn’t taken from Vice President’s Mike Pence’s all-male meeting about health insurance coverage in 2017. (Source, with edits: Wikimedia Commons)

Argument #1: Hat pins pose danger to innocent men

Countless newspaper opinions published across the country provided an onslaught of rhetoric against hat pins, pointing to the danger they poised to men and children on public transportation and on the street. Curiously, the safety of women was rarely, if ever, part of the equation in these opinions, despite male violence almost always precipitating hat pin stabbings.

Rather than address the systemic problem of men harassing and attacking women in public spaces, 20th century lawmakers felt more comfortable arguing that men were actually the ones in danger, so long as women carried hat pins. They flipped the Hatpin Panic debate on itself as they argued that men were the victims and women the aggressors. The danger that women face just by existing in the same space as men is left unacknowledged and unsolved with this line of argument. Thus, the ban on hat pins pushed forward.

If the backlash to hat pins sounds familiar, you may be reminded of the backlash to the #MeToo movement. In the year that followed the inception of a national conversation about sexual harassment and violence against women, the focus shifted from discussing sexual violence against women to discussing how to prevent innocent men from being wrongly accused. This is a tactic used to discredit sexual assault victims, commonly known today as DARVO. It stands for “Deny, Attack, Reverse Victim and Offender.”

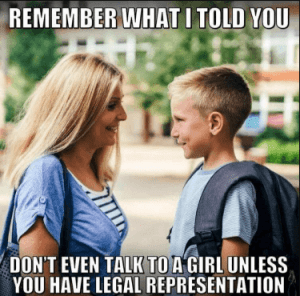

Example of #MeToo backlash in the form of a 2018 meme.

So when the hashtag #HimToo is taken over by Brett Kavanaugh supporters to argue the Supreme Court Justice is actually a victim of false accusations, rather than the woman he allegedly sexually assaulted, just note how little has changed in the line of argument from the modern anti-hatpin folks.

Argument #2: If women are victimized, it’s their fault

It’s the classic “What was she wearing?” argument with a 1900’s twist. While arguing in favor of banning hat pins, a Chicago Vice Commission reasoned that women should not reveal their ankles or wear makeup to attract unsolicited attention from mashers.

After banning their only defensive weapon, this all-male board then took to the time to lecture women on how not to be assaulted. It’s those darn ankles, you tramps!

At its core, this commission argued the onus was on women to not be attacked by men, never the other way around. So not only are women told they can’t defend themselves on the street, if they are attacked by men – it’s their fault.

From typical school dress codes that punish girls for “distracting” boys to the “she was asking for it” attitude that persists in our culture today, there is no shortage of the phenomenon of vilifying women based entirely on how they dress themselves.

- More stories: Yuri Kochiyama At The Intersection of Black Power & Asian Movements

- More stories: Kara Robinson’s Escape From A Serial Killer

- More stories: Enietra Washington: Only Confirmed Grim Sleeper Survivor

In 1910, the Chicago City Council passed an ordinance that banned hat pins longer than 9 inches. Other cities followed suit during the Hatpin Panic, including Baltimore, New Orleans, and Pittsburgh. Women organized protests, attracting suffragists and other liberal women who came to comprise first wave feminism in the U.S. And just like the work toward voting rights, abortion rights and equal pay, early 1900s women responded to unfair laws with public protest, their hat pins in hand.

How the Hatpin Panic Ended

The Hatpin Panic surely would have continued to escalate, but World War I had other plans. As national priorities shifted from regulating women’s clothing to global war, male panic surrounding the use of hat pins subsided. By the 1920s, women’s fashion shifted in favor of more pragmatic, smaller hats, and the Hatpin Panic officially came to an end.

So what really happened during this period? As the U.S. entered the 20th century, women reached new levels of autonomy and independence never seen before. They worked outside the home, earned decent wages, and enjoyed the comforts and entertainment that cities had to offer. But to protect themselves against the dangers that lurked nearby, women used hat pins against the mashers who meant them harm.

1902 newspaper cartoon portraying woman stabbing a masher on the street with her hat pin. (Source: Sallie Slick and her Surprising Aunt Amelia – Philadelphia North American)

True to form, lawmakers and other public officials flipped the hatpin debate on its head, portraying men as victims and women as the aggressors. It was effective, and countermeasures against hat pins went into effect across the country. Women responded to the measure with national protests and grassroots mobilization.

Today, we continue to have this same fight, over and over. It’s never stopped. Laws that seek to limit female rights are written and passed by men, and ardently protested by women across the country. One hundred years ago, women fought for the right to defend themselves from predatory men with hat pins. In 2017, women fought the right to defend themselves from sexual violence by predatory men with the #MeToo movement.

So, has the Hatpin Panic really ended? Or do we continue to fight the same fight, just with a different hat on?

0 Comments