Masako Katsura: Japanese Billiards Player Who Broke Gender Barrier

A headline from a 1952 story from The Times-Mail reads, “Masako Katsura, A Japanese War Bride, Is Billiard Ace” (Source)

February 21, 2023 ~ By Shari Rose

How Masako Katsura fought to compete against the world’s best 3-cushion billiards players in the 1950s

As the first woman to compete for a world billiards title in the U.S., Masako Katsura blew audiences away with her larger-than-life trick shots and competitive edge. But as a Japanese-American woman in a sport dominated by men in the 1950s, social constraints out of her control should have prevented her from playing against the best. However, her incredible skills and commitment to the sport caught a world on fire that thought it already knew what a woman could and could not do.

Masako Picks Up Billiards in Tokyo as a Teenager

Masako Katsura was born in 1913 in Tokyo, Japan. As a young girl, her petite stature made her weaker and less physically developed than others her age. Since her mother owned a pool hall in town, she encouraged her daughter to learn billiards and gain some muscle in the process.

“I was weak when I was young, and I was tired all the time,” Masako told The Sacramento Bee in 1952. “So my mother wanted me to play billiards to give me exercise and make me stronger.”

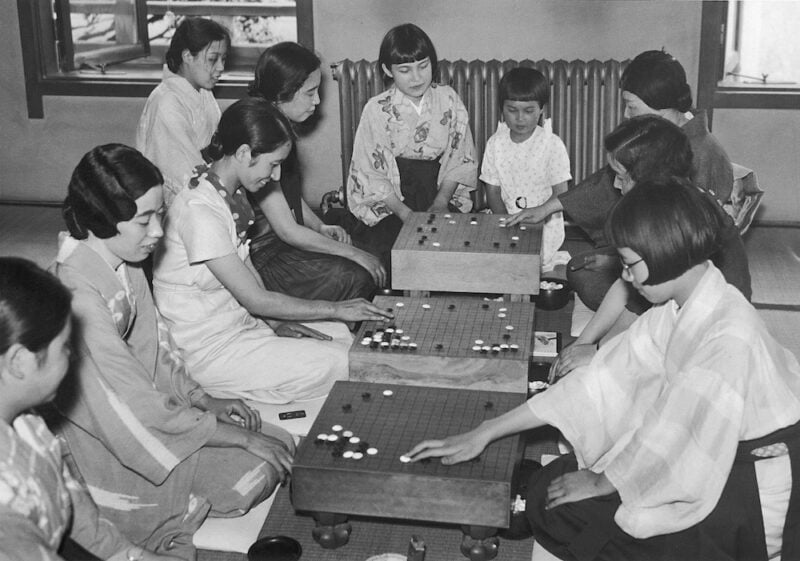

A women-only go billiards parlor in Japan, taken on March 8, 1937. (AP Photo)

At age 14, Masako began working as a pool hall attendant. Her brother-in-law taught her how to play 3-cushion billiards, an advanced version of the game that is played on a table without pockets. Players must shoot a cue ball so that it hits one object ball, then the rail cushions three times, then finally a second object ball.

Despite the difficult nature of 3-cushion billiards, Masako quickly found her passion. She practiced for hours every day, and watched how other players approached the sport, emulating their style of play and inventing trick shots of her own.

While billiards in the U.S. was a male-dominated pastime throughout the 1900s, both male and female Japanese players were welcome to enjoy the sport in the 20th century. In fact, it was very common for young women to work as attendants in pool halls throughout Tokyo. However, on the professional level, billiards largely remained reserved for Japanese men only.

As a teenager, Masako Katsura continued to improve her game as well as her physical strength. At just 15 years old, she won the women’s straight rail championship in Japan. After her win, Masako focused on perfecting her straight rail and 3-cushion billiards abilities, learning how to complete different angle shots and physical maneuvers to accommodate for her small size.

In 1937, Masako caught the attention of Kinrey Matsuyama, one of the best billiards players in Japan and a renowned 3-cushion champion. He agreed to become her coach, and she spent the next decade evolving her billiards game in Tokyo.

Masako Katsura Performs Billiards Exhibitions for American Soldiers

After World War II ended, Masako demonstrated her unbelievable billiards skills in one-woman exhibitions for American soldiers stationed in Japan. At just 5 feet tall and less than 100 pounds, Masako captivated her male audiences by performing near-impossible trick shots in pool halls throughout Tokyo. One such enraptured audience member was U.S. Air Force Master Sergeant Vernon Greenleaf. Greenleaf and Masako began a relationship after he watched her show one night, and they married two years later.

Masako’s feats were so popular that word spread among American soldiers returning home about a Japanese woman who could outplay any man at billiards. Rumors of Masako’s talents eventually reached Welker Cochran, a world-renowned champion in 3-cushion billiards. Cochran asked his son, who was stationed outside Tokyo, to watch Katsura Masako’s show and determine if these larger-than-life rumors were true.

Cochran’s son later sent a 12-page letter that excitedly confirmed Masako’s prowess at the billiards table. Convinced by what his son had witnessed, Cochran formally invited Masako to compete in a 3-cushion championship in the U.S.

By 1950, Masako had placed 2nd multiple times in Japan’s national 3-cushion championship and looked to test her skills against new competitors. She and Greenleaf took up Cochran’s offer, and they moved to Northern California in December 1951.

- More stories: Yuri Kochiyama at the Intersection of Black Power & Asian Movements

- More stories: The Forgotten Anti-Filipino Watsonville Riots of 1930

- More stories: Israel Has Killed a Record Number of Journalists & Aid Workers in 6 Months

Masako Becomes First Woman to Compete for World Billiards Title

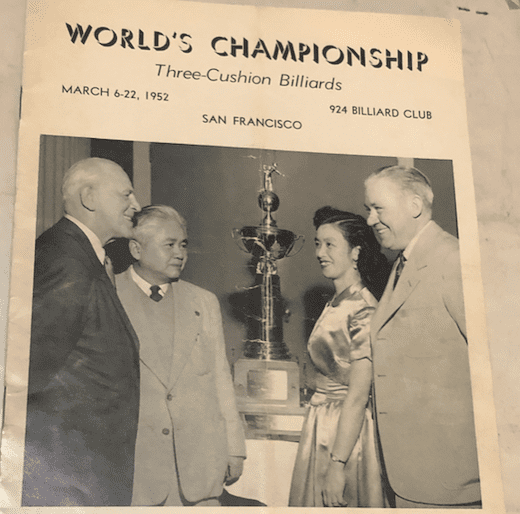

After arriving in the U.S., Masako Katsura worked with Welker Cochran to prepare for the 1952 World Three-Cushion Billiards Championship, just a few short months away. Through Cochran’s request, the championship committee agreed to extend an invite to Masako, and she became the first female player to compete for a world billiards title at 38 years old.

Upon learning that a woman would play 3-cushion billiards against the best male players in the world, many in the sports community viewed her entry as nothing more than an attention-seeking publicity stunt. That is, until they watched her play.

In early March 1952, Masako faced her first opponent in the competition, Irving Crane. She lost to Crane, but then won her next match against Herb Hardt with a score of 50 to 42. Next, she played Joe Chamaco and lost. But again she rallied in the next match and beat Joe Procita at 50 to 43.

During the competition, Masako played the best billiards players on the globe, including Willie Hoppe, Art Rubin, Jay Bozeman, and her former coach, Kinrey Matsuyama. In her final match, she squared off against Ray Kilgore, and beat him in a massive upset.

At the end of the 1952 World Three-Cushion Billiards Championship, Masako placed 7th out of the 10 best international 3-cushion billiards players. In just a matter of weeks, she proved on an international stage that women could face off against the best players in a male-dominated sport, and win matches just like anyone else.

A program flyer from the 1952 World Three-Cushion Championship features Willie Hoppe, Kinrey Matsuyama, Masako Katsura, and Welker Cochran on the cover. (Source)

After defending champion Willie Hoppe beat her in 40 innings, he spoke admiringly about Masako Katsura’s potential at the table: “If this little lady continues to compete in tournaments, within two years she’ll be capable of defeating any man. Right now she knows more about execution of safety shots than any of us.”

Exhibition Tour in the U.S.

After Masako’s success at the World Three-Cushion Billiards championship in San Francisco, Welker Cochran sought to capitalize and organized exhibition matches in major cities across the U.S., including New York, Chicago, Detroit, Kansas City, and Portland. During these exhibitions, Masako performed shockingly difficult trick shots and played hours-long matches against Cochran.

Masako Katsura made headlines when she broke a world record by scoring 10,000 continuous points at straight rail. The effort took over four hours, and she only stopped because 10,000 was a benchmark figure. Another trademark trick shot of hers involved beer bottles. She placed two billiard balls on top of two empty beer bottles, caromed a cue ball to hit an object ball, and knocked the two balls down without toppling the beer bottles.

Because Masako was as tall as the 5-foot cue stick she wielded, she learned how to use every available angle to her advantage, occasionally half-climbing onto the table to secure her shot. Local sports journalists marveled at Masako’s calm yet decisive demeanor as she knocked down shot after shot in front of large crowds. During a 3-cushion billiards match against Cochran in New York, sports writer Jimmy Cannon described her style of play:

“The woman hurried around in a rapid walk,” he wrote. “Once she had surveyed the table, crinkling her forehead in meditation, there was no hesitation. The stroke was quick but unhurried. People gazed at her through the faint nicotine haze with reverence. When Miss Katsura missed a shot, her eyes pulled into a squint, her face frozen into a grimace of regret. When she scored, the people applauded.”

Since Masako continued to learn English during her time in the U.S., she kept her interviews short and to the point during the exhibition tour. In a 1952 Time Magazine article, Masako was asked how she handles playing such a difficult game with the pressure of a large audience in front of her. She said succinctly: “I am alone at the table.”

A headline from The Sacramento Bee reads, “Wife Of GI Proves Pool Can Be Woman’s Game” on October 30, 1952. (Source)

Cochran often spoke for Masako in interviews while highlighting her impressive skills. As a former 3-cushion champion who exited his retirement solely to play exhibitions with her, Cochran’s words had a massive impact on billiards and pool players across the country. In an interview with The Kansas City Star on May 5, 1952, Cochran explained what made Masako such a formidable player:

“Intuitively she makes the right shots and plays the right angles,” he said. “She has the touch which makes it extremely difficult to acquire. She will spend four hours practicing, then play another four in her exhibitions and think nothing about it.

“She constantly amazes me by the shots she makes and by her little inventions which compensate for her lack of size,” he continued.

Media Coverage of Masako Katsura

Though most newspaper stories about Masako Katsura were positive, journalists still relied on sexist and racist stereotypes to make sense of this one-of-a-kind billiards player. One such 1952 piece from Rita Fitzpatrick at the Chicago Tribune proclaimed that Masako “descended on the United States last December with results almost akin to the atomic bomb.”

The reporter also wrote that Masako was a “wisp of a woman who looks like she would have difficulty blowing a feather away” but she had “an exotic feminine touch” because she typically wore satin kimonos and high heels while playing.

A headline from Detroit Free Press reads “Look! Real Japanese ‘Cue-tee’” on May 13, 1952. (Source)

The following month, a positive story centering on Masako’s achievements from an Indiana paper labeled her a “lithe Japanese war bride.” A few months later, a piece from The Sacramento Bee opened with fascination and a touch of confusion about Masako’s interests: “Seeing a woman playing billiards in a pool hall is strange. But stranger still is seeing her outplay every man in the place.”

Furthermore, nearly every article that covered Masako at length had details concerning her exact height and weight. Though coverage had the air of admiration and an intent to compliment, a majority of journalists of the era wrote about her as if she were a fascinating yet strange novelty, and marveled at how she would be able to do anything outside domestic life while being so petite and feminine. Once when questioned about her domestic duties in the home, Masako answered: “I cook, yes. I sew, no. I play billiards.”

Masako was also often asked about her life at home with her husband. She said that she and Vernon Greenleaf played billiards most nights, and Greenleaf once joked in an interview that his wife “never had any trouble beating” him.

- More stories: The Triumphs of Edward Gardner at the 1928 Bunion Derby

- More stories: California’s History of Anti-Asian Laws and Riots

- More stories: How the Hatpin Panic Changed 20th Century Gender Politics

Masako’s Later Career as Billiards Declines in Popularity

After finishing her national exhibition tour with Welker Cochran, Masako Katsura continued to play in world billiards tournaments. In 1953, she competed in the World Three-Cushion Billiards Championship in Chicago and once again faced the biggest players in the world, many of whom she played in the prior year.

Masako won her matches against Jay Bozeman, Zeke Navarra, Joe Chamaco, and Herb Lundberg. She finished the tournament in 5th place with a 5-5 record.

Bozeman spoke highly of Masako after losing to her: “We’ve found it hard to believe that a woman could actually step into the best billiard championship in the world and hold her own. Miss Katsura is one of the finest players I’ve faced in a world’s tournament.”

The following year, Masako agreed to play 10 exhibition matches against Danny McGoorty, a former pool hustler and now-famous billiards player. Throughout the matches, Masako switched evenly from shooting left-handed and right-handed, delighting audiences and frustrating her opponent. McGoorty said of her performance:

“I played hard and threw her all the dirtiest stuff I knew,” he said. “If you had the slightest idea of easing up because she was only a cute little girl, you were dead. She would murder you. She would take those balls away from you and stick them right up your pooper. She was tough to play because of the way the crowd reacted to her. Every time she shot, the whole crowd leaned, hoping she would score the point. When I shot, they learned the other way. Her short angles were terrific. On short angles, she had everybody out looking for work.”

At the 1954 World Three-Cushion Billiards Tournament in Buenos Aires, Masako placed fourth. Following the competition, she took time away from the sport and published two Japanese-language books about how to play billiards. She appeared in some television spots in the late 1950s, but the national popularity of 3-cushion billiards was waning. By 1960, the annual 3-cushion championship ended due to lack of public interest.

A headline from The Tacoma News Tribune reads “Masako Katsura Reaches Billiard Tourney Finals” in Buenos Aires on October 20, 1954. (Source)

One of Masako Katsura’s final public appearances as a billiards player took place during a small tournament with Harold Worst in Grand Rapids, MI. She lost 6 out of 7 matches against him in 1961. Following those losses, Masako did not publicly play again for the next decade. Her husband, Vernon Greenleaf, died in 1967, and Masako moved to Pasadena to begin her retirement.

Masako Katsura’s Retirement and Death

In 1976, Masako made a surprise appearance at Palace Billiards in San Francisco after a 15-year absence. To the crowd’s delight, she scored 100 points in a row without a single miss. She bowed to the ecstatic audience, and was never seen playing billiards again.

The same year, she was inducted into the Women’s Professional Billiard Association Hall of Fame in 1976 as one of the sport’s all-time greatest players.

A Google Doodle from March 7, 2021 features an animated Masako darting around a billiard table. (Source)

In the early 1990s, Masako returned to Japan and spent her final days in Tokyo. She died in 1995 at the age of 82.

Conclusion

In 1950s American culture, Masako Katsura’s sex, race, and size should have stopped her from becoming a professional billiards player. But she held her own against the best male players in the world, and even beat a few of them multiple times. She captured the imaginations of the public in both the U.S. and Japan, and worked to demonstrate that her perceived limitations were actually strengths all along.

Masako’s skills and dedication to the sport transcended stereotypes during an era of American history that struggled to understand one another beyond racial and gender identities. She was a positive force in representing women and Japanese-Americans in a sport that was largely dominated by white men. Masako demanded respect and received it from the best billiards players in the world – her peers.

In an interview with the Sacramento Bee in 1952, Masako spoke openly about the lack of women in the sport of billiards. She commented that she had only met one other female player since coming to the U.S., and she thought that was wrong.

“Here, a billiard parlor is thought of as a man’s place,” Masako said. She lamented that women were missing out on a great sport.

With a slight smile, she told the reporter: “You know, if someone had a billiard parlor for women only, that would be good.”

- More stories: Esther Jones: Betty Boop’s Original Influence

- More stories: George Washington’s Fight for Smallpox Inoculation in Revolutionary War

- More stories: The Fate of Margaret Morgan in Prigg v. Pennsylvania

0 Comments