Reckless Eyeballing: How Matt Ingram’s Story Reveals Fear of Black Sexuality

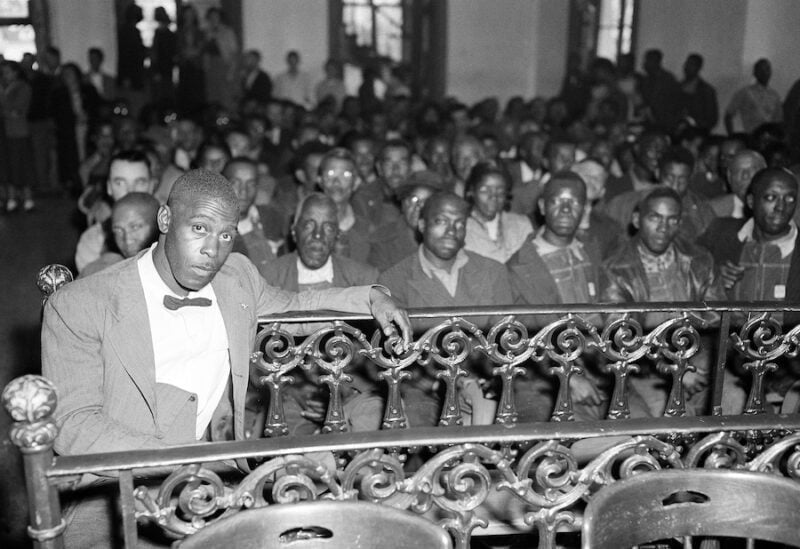

Matt “Mack” Ingram, accused of assaulting a white woman by “reckless eyeballing”, shown during jury deliberation in Yanceyville, N.C., on November 15, 1951. (AP Photo/Rudy Faircloth)

March 7, 2023 ~ By Shari Rose

In 1951, Matt Ingram was arrested and charged with intent to sexually assault a 17-year-old girl based on a look he gave her while standing over 70 feet away. Accused of “reckless eyeballing” toward a white girl during the Jim Crow South, Ingram faced years of imprisonment and thousands of dollars in legal fees for the crime of looking at a person. Despite Ingram’s decades-long reputation as a good man and his lack of a criminal history, one accusation centering on his gaze toward a frightened white girl destroyed everything that he and his family built in an instant.

Matt Ingram’s Life Before Reckless Eyeballing Accusation

Matt Ingram, also known as “Mack,” was a 44-year-old tenant farmer who lived in Yanceyville, NC, with his wife and nine children. By the economic standards of the time, Ingram was more financially comfortable than other farmers in town, including many white residents. He owned a number of his own tools and equipment, had a few mules on the property, and even owned an old automobile that he drove around town.

According to the white locals who lived there, Ingram was “a good Negro” who didn’t cause trouble. During the Jim Crow era, Yanceyville was a racially segregated, tobacco-farming town. Local residents knew each other in this small town, including the 17-year-old white girl who accused Ingram of assaulting her. The girl’s name was Willa Jean Boswell, and she lived on a nearby farm with her parents and four siblings.

What Happened: Matt Ingram’s Perspective

On the day of the incident in 1951, Matt Ingram said he drove to a few homes in the area to ask about borrowing a trailer for the day because he needed to transport hay from a neighbor’s farm. Ingram said he stopped at the Boswell house to ask Willa’s father if he could use their equipment. No one was home, so he began walking the property to find Mr. Boswell. The family knew who Ingram was, as he had visited their home before.

Ingram said he entered the woods near the property, and found Willa walking with a hoe in hand toward her family’s tobacco field. He stopped walking as she continued on the path, then he turned around and headed back to the road. Ingram couldn’t find Mr. Boswell, so he drove to another farm. He borrowed that farmer’s trailer, and finally drove to a third farm. He was loading hay on that property when he was arrested by police.

- More stories: Edward Gardner: How Black Athlete at 1928 Bunion Derby Became a Symbol of Hope

- More stories: The Fate of Margaret Morgan in Prigg v. Pennsylvania

- More stories: How Stetson Kennedy Infiltrated the KKK & Changed the Jim Crow South

What Happened: Willa Jean Boswell’s Perspective

In the morning, Willa said her father and brothers left home early to work on the family’s tobacco field. She left a little later to join them, carrying a hoe in her hands.

Less than one-tenth of a mile into her journey, Willa said she saw Ingram driving his vehicle along a dirt road. She said he slowed down as he passed her, then continued driving on. She said she became frightened when he popped his head out the window to look at her.

Willa said she continued down the path, entering a wooded area before the route ended at the tobacco field. She spotted Ingram walking toward her in the woods. She said he stopped walking about “65 or 70 feet from her,” before he turned back and headed toward the road again. She said she continued walking and cried when she reached her family. Her father and brothers alerted police, and Ingram was arrested later that day.

Due to the crime of looking at Willa Jean Boswell in the woods, Matt Ingram was arrested and charged with intent to rape.

Reckless Eyeballing During Jim Crow Era

The act of leering or expressing sexual interest, actual or imagined, by a Black man toward a white woman was a criminal offense, as well as a lynchable one, during the Jim Crow era. The belief that white women had a purity that must be protected from men of color, particularly Black men, is a major tenant of white supremacy and its effects continue to this day. Even outside Jim Crow states, the white supremacist belief that white women were only allowed to have relationships with white men pervaded all areas of the country, and helped incite violent race riots such as the 1930 Watsonville riots in California that targeted Filipino farmworkers.

The murder of Emmett Till is perhaps the most horrific example of this racist phenomenon, as the 14-year-old was tortured and murdered by two white men for allegedly flirting with a white woman. The teenager was killed less than four years after Ingram’s reckless eyeballing arrest.

- More stories: John Mitchell Jr.’s Relentless Fight for Justice at The Richmond Planet

- More stories: Echoes of Slave Patrols in ICE Raids: What Abolitionists Can Teach Us

- More stories: How a Retractable Syringe Exposed Powerful Group Purchasing Organizations (GPOs)

Ingram was arraigned in Caswell County and awaited his upcoming trial in jail. He was represented by E. Frederick Upchurch, a 76-year-old white lawyer who was well-respected in the community. It’s believed that Ingram knew Upchurch personally and asked for his help because he could not afford a lawyer.

Upchurch arranged for his bail at $1,500. But when Upchurch went to the courthouse, the prosecutor requested that Ingram’s bail be raised to $1,800, which the judge granted.

Ingram’s First Trial

During the first trial, Willa Jean Boswell took the witness stand and tearfully recounted her fear of Ingram when she saw him looking at her. The prosecutor, W. Banks Horton, capitalized on residents’ fear of Black male sexuality, and played up the racial fears that white people harbored of Black men. He even explicitly told the jury that “young womanhood must be protected from n******.”

The judge presiding over the trial, Ralph Vernon, was a local farmer with no legal training. He told Horton to reduce the charge from rape to assault due to an earlier state supreme court decision that determined non-physical assaults could not be classified as rape.

Once the charge was adjusted, Vernon found Matt Ingram guilty of assault on a female and he was sentenced to a maximum of two years in jail. Ingram’s lawyers immediately appealed, and his case went to the Superior Court.

NAACP Gets Involved With Ingram’s Case

Ingram’s assault conviction stemming from looking a white girl caught national attention. The NAACP heard about his story, and offered legal assistance for his appeal. The organization sent two Black lawyers with past ties to desegregation cases to help Ingram get his assault conviction overturned in Yanceyville.

Another group that heard about his story was the Civil Rights Congress (CRC), a U.S.-based group with Communist Party affiliation. Much to the NAACP’s dismay, the CRC engaged in public campaigns against Ingram’s conviction, writing about it extensively in its publication and pushing for letter-writing campaigns in North Carolina. The NAACP disagreed with these tactics, believing them to infuriate white authorities and embolden their hostility toward Black defendants.

In its publication, “The Daily Worker,” the CRC wrote headlines like “Negro Was Framed For Doing Too Well On Farm” and “Negro Jailed Because White Woman Saw Him.” These stories, though perhaps controversial for the era, were effective in keeping attention on Matt Ingram’s case from readers across the country.

- More stories: How Isaac Wright Jr Became a Lawyer & Overturned Life Sentence

- More stories: Marshall Sherman’s Capture of Virginia Battle Flag at Gettysburg

- More stories: How Journalist Ruben Salazar Gave Voice to Chicanos in Los Angeles

Subsequent Trials

As part of Ingram’s appeal process, his case was presented before a Superior Court grand jury. The all-white, 18-person jury heard his case and “returned an indictment for assault with intent to rape.”

The second trial proceeded with a jury of 8 white jurors and 4 Black jurors. The group could not reach a verdict in the case, and the judge declared a mistrial. The prosecutor then renewed the charge, and Ingram’s court date for his third trial was set for November 1952.

Matt Ingram’s third trial took place in Superior Court with an all-white jury. Due to the racist press coverage leading up to the court date, Ingram’s lawyers asked the judge to move the venue to a more neutral location. Local newspapers had already decided on Ingram’s guilt, and his story continued receiving national attention as well.

Judge Frank M. Armstrong rejected the request to change the venue. Additionally, Ingram’s lawyers pointed out that an all-white jury in a racially charged trial like Ingram’s was a form of discrimination against their client. Furthermore, the pool from which the jury was selected was a local community that had 49% Black residents. His lawyers said that the 76-person pool from which the jury was selected was somehow composed of all white residents.

Despite clear evidence of racial bias and discrimination, Judge Armstrong denied all the defense’s motions, and the trial proceeded with an all-white jury in a town whose local newspapers firmly sided against Ingram.

During the trial, Willa Jean Boswell recounted that she recognized Ingram when she saw him in the woods. Her father also testified in court that he knew Ingram. They acknowledged that it was normal for Ingram to travel the route he did while visiting other homes in the community. Furthermore, Willa confirmed that Ingram never touched her or made a motion to walk closer to her in the woods that day.

Judge Armstrong Gives Contradictory Instructions to the Jury

After testimony closed, Judge Armstrong appeared to confuse the jury about how to proceed next. As historian and author Mary Frances Berry wrote about the trial, “Judge Armstrong gave a series of confusing instructions,” including his statement to jurors that “it is not always necessary that there be some physical contact with the person alleged to have been assaulted.”

Judge Armstrong then said that if “by intentional threats or menace of violence, such as looking at a person in a leering manner, that is, in some sort of sly or threatening or suggestive manner; watching one and then following one, he causes another to reasonably apprehend imminent danger, and by such conduct cases one to become frightened and and run or causes one to do otherwise than he would have done, then he is guilty of an assault.”

Ingram’s lawyers objected to Judge Armstrong’s additional commentary to the jury, an objection which Judge Armstrong rejected.

Puzzlingly, Judge Armstrong then informed the jury that they must acquit Ingram if they find he only looked at Willa in a threatening or suggestive manner. This statement completely contradicted his earlier instruction, and even caused the court solicitor to walk over to the judge and whisper to him.

After his contradiction was pointed out to him, Judge Armstrong then told the jury: “Under the last instruction, if I said you would find him guilty, the court instructs you to disabuse your mind of that because the court intended to say you would find him not guilty.”

The all-white jury found Matt Ingram guilty of assault.

- More stories: Esther Jones: Betty Boop’s Original Influence

- More stories: The Lives of Ferguson & Black Lives Matter Activists Cut Short

- More stories: How School Portables Became Permanent Classrooms

Matt Ingram Again Found Guilty

Judge Armstrong sentenced Ingram to a 6-month jail sentence with physical labor. But he then suspended the sentence for five years as long as Ingram paid court fees and promised to “remain on good behavior and not violate any laws, make his personal appearance at each November term of the court, and show by himself and witnesses that he has kept the terms of this judgment.”

Ingram’s lawyers again appealed the conviction. They argued that the judge’s contradictory statements to the jury, his refusal to change the venue, and the racial makeup of the jury in a town where half of the population is Black were reasons to advance Ingram’s case to the highest court in the state. After some legal maneuvering, the North Carolina Supreme Court agreed to hear Ingram’s case.

Ingram Appears Before the State Supreme Court

Chief Justice William A. Devin presided over the case. After proceedings ended, he and his fellow justices found that Ingram was not guilty. Devin wrote that, while Willa was no doubt frightened, “that fact alone is insufficient to constitute an assault in the absence of a menace of violence of such character, under the circumstances…”

In his argument, Devin wrote explicitly that “no assault was committed.” Using Willa’s own testimony, he argued that Ingram did not say a word or make a gesture toward the teenager. He simply turned around and walked back the way he came that day.

In closing, Devin wrote that Ingram’s gaze merely represented “what may have been in his mind. Human law does not reach that far.”

Two and half years after his arrest, the North Carolina Supreme Court overturned Matt Ingram’s conviction and he was cleared of all wrongdoing. But the social and economic damage was already done to him and his family.

Ingram’s Conviction Is Finally Overturned

Matt Ingram and his wife, Linward, never financially recovered from the legal battles and racist press coverage they endured. Ingram lost work in Yanceyville as the farmers that he had prior relationships with were afraid to hire him and harm their own reputations.

Ingram was forced to sell off the farming equipment he owned to keep his family afloat. When he was arrested in 1951, his wife was pregnant. But because the residents of Yanceyville turned against the Ingram family after he was charged, Linward and their 11-year-old son had to work the fields themselves and keep the farm alive while he was in jail.

Due to the national publicity of the case, the family initially received some money and clothes, but support eventually dried out. Even after the state supreme court decision, the Ingrams were ostracized in Yanceyville, and had to conduct their business in nearby Danville.

Matt Ingram died in 1973. Linward lived for another 30 years and died in 2003.

Conclusion

The compounded racial injustices that Matt Ingram and his family endured before, during, and after he was accused of looking at a white teenager were extremely commonplace before the Civil Rights Movement, though echoes of it continue today. Indeed, just four years after Ingram’s arrest, 14-year-old Emmett Till was lynched for allegedly flirting with a white woman in one of this nation’s most despicable examples of anti-Black violence.

Policing Black male sexuality was and continues to be an effective tool for upholding white supremacy, both socially and economically. It’s no coincidence that Ingram was financially better off than many white residents in a racially segregated town, and he still lost everything despite being cleared of all charges by the state’s highest court.

The white supremacist phenomenon of treating Black sexuality as a crime, punishable by loss of economic status, imprisonment, or death, has effects that endure to this day. Whether it’s former Maine Gov. Paul LePage declaring that Black men come to his state to “impregnate a young white girl before they leave,” or Republican Sen. Mike Braun saying in 2022 that he’d prefer if states decided on the issue of interracial marriage, essentially re-imposing the ban that Loving v. Virginia lifted on interracial marriage over 50 years ago, racial fear concerning Black male sexuality continues to echo throughout American culture today.

- More stories: Yuri Kochiyama at the Intersection of Black Power & Asian Movements

- More stories: Prison Gerrymandering Is a Modern 3/5 Compromise

- More stories: Book Banning in the U.S. at an All-Time High

I can not stop laughing. It is so hard to believe that human beings were subjected to this nonsense. Attempted rape for looking at her.

I feel like Celie in the Color Purple. “Until you do right by me, everything you even think about gonna fail!”

Until this country makes this right, it can’t go forward.