How Lani Ka’ahumanu Propelled Bisexual+ Visibility

Lani Ka’ahumanu speaks about her bisexual advocacy work over the decades in an interview with Surviving Voices in 2018. (Source)

February 10, 2022 ~ By Shari Rose

Updated April 14, 2024

Ka’ahumanu advocates for bisexual+ inclusion and visibility in a culture that expects a rigid dichotomy of either gay or straight

Lani Ka’ahumanu sought to achieve acceptance for the bisexual+ identity (bi, pan, fluid, and queer) in the gay and lesbian community, and succeeded in generating national visibility for bisexuals throughout the U.S. Her extensive writing career and grassroots activism in San Francisco advanced a growing understanding of bisexuality+ and cultivated pride in an LGBTQ identity that is historically disparaged and excluded from both gay and straight spaces.

Lani Ka’ahumanu’s Early Life

Ka’ahumanu speaks in an interview with OUTWORDS in 2020. (Source)

Lani Ka’ahumanu (pronounced Kah-Ah Hoo-MAH-Noo) was born on October 5, 1943 in Edmonton, Canada. Before her birth, her mother immigrated from Japan and moved to Hawaii, where she eventually met Ka’ahumanu’s father, a Minnesota native stationed on the island during World War II. Ka’ahumanu’s ancestry is a mix of Japanese, Hawaiian, Irish, and Polish Jewish.

Unlike her mother and sisters, Ka’ahumanu has lighter skin and hair color, and says she faced less racial discrimination than other members of her family as a result.

“My mom would say to me, ‘You’re lucky to have the golden skin,’” Ka’ahumanu said in 2018. “I didn’t have to deal with the racism that two of my sisters did, and my mother … Because the world is so, ‘You’re either this or this.’ So as a mixed heritage bisexual, I just stand up for the continuum.”

Her family moved to San Francisco, and then to San Bruno when she was four years old. Ka’ahumanu says she showed an early knack for organizing as a child.

“I was the kid that organized everything. I organized the Kool-Aid stand. The Kool-Aid stand wasn’t good enough for me. So I added a puppet show. Then I’d have a Kool-Aid stand and I had a circus,” she said, laughing.

Ka’ahumanu attended St. Robert’s School and began dating the captain of the football team when she was 16. They fell in love and got married when she was 19 years old. Her husband became a teacher at their old high school.

The couple had two children together. As a stay-at-home mom, she embraced the suburban lifestyle. She ran the Art Corner at her kids’ school and was heavily involved with Little League activities.

Women’s Liberation Opens Ka’ahumanu’s Eyes

While at home in the 1960s, Lani Ka’ahumanu watched talk shows that often invited activists connected with the women’s liberation movement to speak about feminism. That exposure to a new, progressive way of thinking changed her perspective for the rest of her life.

Photo of Ka’ahumanu from her website. (Source)

“My consciousness was broken open, and I got involved with the anti-Vietnam War movement,” she said. “As a housewife, with my limited experience of the world, even if I was in my mid-20s, where had I gone? I hadn’t gone anywhere really.”

Ka’ahumanu and her husband engaged with the anti-war movement and supported civil rights initiatives in their area. Nonetheless, Ka’ahumanu found herself becoming more and more unhappy. She says she cried a lot during this period and did not understand why.

One day in the early 1970s, her husband shocked her when he said that she needed to leave him. He told her that she never had a life of her own, and she agreed.

Ka’ahumanu got her own apartment about a mile from their kids’ school and started taking night classes. A year later, she and her husband amicably divorced and she moved to San Francisco. She attended San Francisco State University as a full-time student when the school’s burgeoning women’s studies program was established. Ka’ahumanu met a wide range of feminists, lesbians, and activists from different walks of life, and felt that she had finally found her home.

While majoring in women’s studies, Ka’ahumanu worked as a waitress at a jazz club. She says she enjoyed the dating scene for some time and took advantage of this new freedom. “I didn’t want to settle down, I didn’t want to be with anybody. I just wanted to find out what I could do, where I was going,” she said.

More stories: Why Is Bisexuality an Invisible Majority in the LGBTQ Community?

More stories: Amelio Robles Ávila: Transgender Fighter In Mexican Revolution

More stories: Brenda Howard: Mother of Pride & Bisexual+ Rights Activist

Ka’ahumanu Comes Out As A Lesbian

Over time, Lani Ka’ahumanu was determined to figure out her own sexuality and eventually came to a conclusion. In 1976, she came out as a lesbian.

“I knew I always loved women,” she recounted in a 2020 interview. “I knew I was attracted to women. I think being raised Catholic and being so repressed, I didn’t connect it with sexuality or anything … But the feminist movement lined it up … It was an awakening, an amazing awakening.”

In her newfound community, Ka’ahumanu was embraced and supported by fellow lesbians. In the late 1970s, she continued to pursue activism. She immersed herself in pro-choice rallies, civil rights demonstrations, and marched with the Lesbian Mothers group in San Francisco as queer women were losing custody of their children after they came out of the closet.

Lani Ka’ahumanu speaks about her LGBTQ advocacy work in San Francisco in a 2018 interview with Surviving Voices. (Source)

“Coming out as a lesbian was a political statement, but it was much more than that,” she said. “You were part of this growing community, this giant wave. There was so much support and cheering section, literally. It was like, ‘Yeah, you’re in the club!’”

Shortly after she came out publicly as a lesbian, she spoke with her ex-husband. He informed her that she was actually bisexual. Ka’ahumanu was adamant that bisexuality did not exist. But that sentiment would be short-lived.

Lani Ka’ahumanu Realizes She’s Bisexual

In 1979, Ka’ahumanu graduated from San Francisco State with a degree in women’s studies. She moved to Mendocino County for the summer and worked as a chef at a clothing-optional resort called the Village Oz.

One day at work, she met a young bisexual hitchhiker, and they immediately hit it off. They discussed femnist theory at length and found they had a connection, including sexually. Within a few weeks, they were sleeping together in secret.

But the couple was soon discovered by none other than the owner of the resort. “[The resort owner] caught us one day making out in the storage room, and it was all in the open,” Ka’ahumanu said.

After being caught dating a man, Ka’ahumanu says her biphobia prevented her from admitting who she really was.

Ka’ahumanu explains how she came out as bisexual+ after originally identifying herself as a lesbian in a 2020 video with I’m From Driftwood.

“Coming out as bisexual, my internalized biphobia was just, ‘I’m not like that.’ When I was an out lesbian, I fell in love with a man. Whoops,” she said with a smile.

When the summer ended, Ka’ahumanu knew moving back to San Francisco meant she would face backlash from lesbians for dating a man.

“I couldn’t even say I was bisexual,” she said. “I said lesbian-identified-bisexual so quick because I just couldn’t say bisexual by myself, I had to prove that I wasn’t a traitor. I didn’t want to be kicked out. It was my community. But the internalized biphobia was enormous. It took years, it really did.”

When Ka’ahumanu returned to San Francisco, she was scorned by the lesbian community. “I was publicly shunned, excluded from gatherings, isolated,” she said. “‘Friends’ told me I was a traitor for going back to men. That I was not to be trusted. That I was hiding in heterosexual privilige. There was no such thing. I refused to be kicked out.”

Ka’ahumanu continued pursuing LGBTQ and feminist activism in the city, taking part in demonstrations and marches, much to the chagrin of many lesbian advocates who viewed her as a traitor. She also continued to date the man she met at Village Oz. She became known as the “lesbian who fell from grace,” with one activist publicly declaring to other queer women that Ka’ahumanu’s genitals were “tainted” from having sex with a man.

But Ka’ahumanu refused to be removed from the place she felt truly at home. “I’m still doing the work,” she said. “I’m still a member of the community that I was before.” Despite the biphobia, she found a few lesbian activists who supported her as a bisexual+ woman. With enough time, she learned to embrace her identity.

“Whatever stereotype I had in my head, I had to live through every single one of them. And as I met more people, as I talked about it, I thought, ‘Well no wonder I had to say lesbian-identified-bisexual, I was so biphobic I couldn’t do it,’” she said. “But there I was, in love with a man. I was truly in love with this person. And how could that be wrong?”

More stories: Masako Katsura: Japanese Billiards Player Who Broke Gender Barrier

More stories: Why Do Bisexual+ Women Face High Rates of Sexual Assault?

More stories: How the Hatpin Panic Changed 20th Century Gender Politics

Ka’ahumanu Elevates Bisexual+ Visibility In San Francisco

Ka’ahumanu said she worked to figure out how to integrate her bisexual+ identity into the lesbian and gay community. She found that the longer she publicly identified as a bisexual+ woman, the more fellow queer people confided in her with regard to their own bi+ tendencies.

“I became a confessional to all these people that were sleeping with the ‘wrong’ gender,” she said.

Ka’ahumanu realized that increasing visibility for bisexuality was key to its acceptance in the lesbian and gay community. So, she started writing about bisexuality in 1982. Her first article, “Biphobic: Some Of My Best Friends Are” ran in a local lesbian newspaper, and she began networking with other bisexual advocates in San Francisco. Together, they formed BiPOL in 1983, the first bisexual+ political action group in the U.S.

Ka’ahumanu marches in a 1984 San Francisco Pride Parade with BiPOL while carrying two signs that read “Bi And Large” and “Bi-Phobia Shield.” (Source)

In 1987, she co-founded the Bay Area Bisexual Network (BABN) and participated in the March on Washington For Lesbian and Gay Rights the same year. At the annual event, Ka’ahumanu said she recognized the potential to engage bisexuals on the national stage.

A 1990 article from Bay Area Reporter recaps the first National Bisexual Conference in San Francisco. (Source)

After the March on Washington, she said BiPOL received hundreds of letters of support for a national bisexual conference, the first of its kind in the country. So, she and other activists at BiPOL set to work.

Three years later, BiPOL hosted the 1990 National Bisexual Conference in San Francisco. More than 450 people attended, representing 20 states and 5 countries. The conference covered issues that ranged from the modern politics of bisexuality+, AIDS advocacy, feminist theory, and related topics. The conference’s goal was to “Educate, Advocate, Agitate, and Celebrate.”

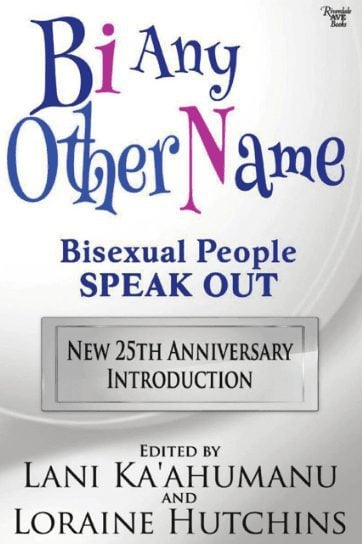

“Bi Any Other Name” Bisexual Anthology

In 1991, Lani Ka’ahumanu and Loraine Hutchins co-edited an incredibly influential book called “Bi Any Other Name.” Largely known as the ‘bisexual bible,’ “Bi Any Other Name” contains essays, poetry, and art from dozens of bisexual people sharing their experiences. The book generated critical visibility for bisexuals who had been consistenly excluded from lesbian and gay works of writing.

In her own words, Ka’ahumanu wrote: “I wanted to walk into my favorite women’s bookstore and find an anthology of bisexual coming-out stories. I wanted to find a book on sexual theory with a thoughtful feminist anaylsis that included bisexuality to answer my questions, to push my thinking, to add my voice … I didn’t walk into my favorite women’s bookstore because I knew what I wanted and needed did not exist.”

One poem that appears in the introduction of Bi Any Other Name is particularly poignant to the bisexual+ experience:

“Bi Any Other Name,” the 1991 bisexual anthology co-edited by Lani Ka’ahumanu and Loraine Hutchins. (Source)

The dichotomies are absolutely

either/or

right/left

light/dark

male/female

masculine/feminine

hetero/homo

white/of color

upper class/working class

middle class/homeless

young/old

able-bodies/differently abled

No room

for all points

in between

No room

for the perfect

Kinsey 1,2,3,4,5

…

But reality is not

this or that

it is

all of this

and

all of that

and

they meet/merge/mingle

in between

“Bi Any Other Name” was nominated for a Lambda Literary Award, a prestigious accolade for gay and lesbian publications. However, a bisexual category for the award did not exist in 1992, so it had to compete in the Lesbian Anthology category. It lost to a lesbian-centered book. Bisexual+ people fought for the next 14 years for the inclusion of bi-focused categories to the Lambda Literary Awards, and they were finally established in 2006.

Bisexual+ Activism Reaches the March on Washington

With the success of the National Bisexual Conference and a growing national understanding of the bi identity, Lani Ka’ahumanu believed it was time for bisexuals to be represented at the Annual March on Washington For Lesbian and Gay Rights.

“The religious, radical right was targeting gay, lesbian, and bisexual and transgender people, she said. “And yet the lesbian and gay movement could not recognize us. They didn’t recognize us as part of the movement. It was completely frustrating.”

To arrange the inclusion of “bisexual” in the march’s official name, Ka’ahumanu organized a campaign involving 12 cities throughout the U.S. She sought to secure signatures from well-known gay and lesbian activists to support the addition of “bisexual” in the march’s name.

“[Gays and lesbians have] been doing a lot of talk, but they haven’t done any walking at all,” she said. “It’s time for them to put their name on a piece of paper that says ‘It’s time to endorse that ‘bisexual’ to be in the name on the March on Washington.’”

LGBTQ demonstrators march in front of the White House at the 1993 March on Washington For Lesbian, Gay, Bi Equal Rights and Liberation. (Source)

Ultimately, Ka’ahumanu’s efforts were successful, though march organizers shortened the label from “bisexual” to “bi.” The march was called the 1993 March on Washington For Lesbian, Gay, Bi Equal Rights and Liberation.

Looking back on her efforts to get bisexual+ representation in the name, she says that the inclusion “meant we were at the national table.”

At the march, Ka’ahumanu was chosen as one of 18 speakers to address the crowd. She was the only bisexual person invited to speak, and she spoke last. Minutes before she was to walk on stage, one of the event’s co-chairs pulled her aside and told her to shorten her speech to two minutes because they were way over schedule.

Ka’ahumanu opened her speech with her now-famous line, “Aloha. It ain’t over ‘til the bisexual speaks.” She said organizers were breaking down the stage around her, but she finished her speech, successfully representing the bisexual+ identity at the nation’s largest LGBTQ platform to date.

More stories: Otherside Lounge: The 1997 Bombing of Lesbian Bar in Atlanta

More stories: Crystal LaBeija: Iconic Drag Queen Who Transformed Queer Culture

More stories: What Daughters of Bilitis Achieved for Lesbian Rights in the U.S.

Ka’ahumanu Establishes ‘Safer Sex Sluts’

After the March on Washington in 1993, Ka’ahumanu leaned into advocacy for safer sex in the age of HIV/AIDS. She found that education materials regarding the deadly condition were split along straight and gay lines, and bisexuals were largely excluded from the conversation.

“As a bisexual, it was all gay, gay, gay, and I was knowing bisexual men who were getting sick and dying too,” she said. “That was pushed aside always, so I became a pretty vocal advocate for bisexuals and HIV/AIDS because we weren’t even listed in the statistics.”

Ka’ahumanu speaks about those in the bisexual+ community lost to HIV/AIDS while standing in front of the AIDS Quilt at the first National Bisexual Conference in 1990. (Source)

In 1992, Ka’ahumanu became a project coordinator at Lyon-Martin Women’s Health Services to spearhead a grant awarded by the American Foundation for AIDS Research. The grant focused on providing education and prevention of HIV/AIDS to lesbian and bisexual+ women, the first of its kind in the U.S.

She founded ‘Safer Sex Sluts,’ a group comprised of young bisexual and lesbian women who interviewed and educated others about having safe sex during the AIDS crisis. They quickly found that performing sketch comedy was crucial in reaching a larger audience. The group started performing skits in bars and on the street, eventually making their way to college campuses.

“They were educational skits because if you get people to laugh and enjoy themselves, they take in a lot more information,” she said.

While visiting colleges, Ka’ahumanu said she always asked students in the audience if their parents had ever spoken with them about safe sex, beyond the scope of not getting pregnant. She said the vast majority had not.

“I think that’s the biggest thing to overcome,” she said. “How do we talk about sex if nobody’s ever talked to us in plain, uncharged language? There’s a way in which it repeats itself. Nobody talks to us, so we have a hard time talking. Silence … adds to homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, all of it.”

Lani Ka’ahumanu Today

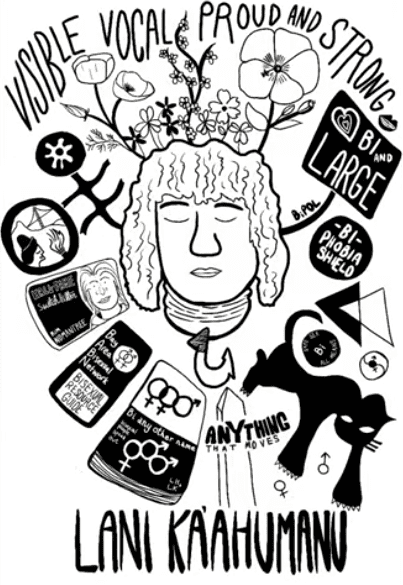

Artwork of Lani Ka’ahumanu created by user Win Mixter on YouTube. (Source)

In the late 1990s, Ka’ahumanu became the first openly bisexual+ person to sit on a national gay and lesbian board of directors. Even today, only 7% of board members in LGBTQ organizations are bisexual. In fact, heterosexuals outpace bisexuals in national board membership at queer organizations. In the 2000s, Ka’ahumanu continued to write about bisexual+ issues, contributing to a range of bi-focused anthologies and publications.

Today, Lani Ka’ahumanu is 78 years old and lives in Sonoma County. She is currently writing two books related to the bisexual+ experience.

More stories: Why Zazu Nova’s Legacy at Stonewall Deserves More Recognition

More stories: Yuri Kochiyama At The Intersection of Black Power & Asian Movements

More stories: These Corporations Don A Rainbow Flag & Donate To Anti-LGBTQ Lawmakers

0 Comments