Otherside Lounge: 1997 Bombing of Lesbian Bar in Atlanta

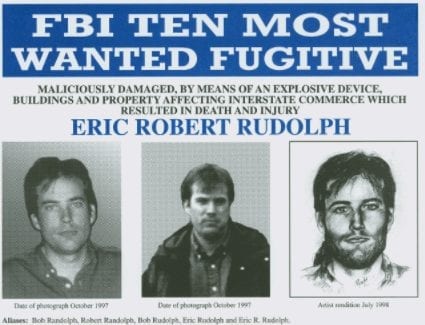

The FBI’s Ten Most Wanted poster for serial bomber Eric Robert Rudolph. (Source)

February 21, 2021 ~ By Shari Rose

Updated January 5, 2022

After gay & lesbian bar Otherside Lounge was bombed by a terrorist in Atlanta, her doors re-opened in defiance of the attack

The Otherside Lounge in Atlanta, Georgia was a beloved lesbian bar and nightclub that provided community, safety, and joy for LGBTQ people in the 1990s. On February 21, 1997, the Otherside Lounge was bombed by a domestic terrorist named Eric Rudolph who sought to harm gays and lesbians who were out and proud. Owners of the Atlanta gay bar, Beverly McMahon and Dana Ford, refused to back down from fear and quickly re-opened their bar in defiance of the terrorism that they and the greater queer community faced.

Atlanta’s Otherside Lounge: A Haven for LGBTQ Georgians

A current view of the Otherside Lounge’s old address at 1924 Piedmont Road. A urology center operates at that address today. (Source)

Opened in 1990, the Otherside Lounge on 1924 Piedmont Road was a favorite local lesbian bar and nightclub in Atlanta. At the Otherside Lounge, queer patrons enjoyed a large dance floor, pool tables, and quieter lounge areas with a full-service bar where they could relax and have a drink. The gay nightclub hosted drag queen events and themed nights, such as jazz, hip-hop, and country.

But this Atlanta lesbian bar was more than just a popular hangout for LGBTQ people to meet others and be themselves in the discriminatory times of the 1990s. The Otherside Lounge served as a safe haven for lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, and trans people thrown out of their homes or otherwise disowned by family members and friends for being who they are.

Beverly McMahon and Dana Ford kept the nightclub open on holidays, even Christmas and Thanksgiving, and it became a home for those without a welcoming place to go. The holidays are often a particularly difficult time for the LGBTQ community, especially during an era where homophobia ran rampant and few laws existed to protect gays and lesbians from discrimination.

Otherside Owners Beverly McMahon & Dana Ford

McMahon and Ford originally met on a blind date in Florida, fell in love, and moved to Atlanta. In 1990, they opened the Otherside Lounge and welcomed two children into the family, Kellyann and Justin. When deciding to open the gay bar, McMahon pointed to the importance of providing a space where everyone felt safe and accepted. In an interview with Georgia Voice, she said, “It was very important to me early on that I would have a business, no matter what it would be, where everyone was welcome: gay, straight, Black, white.”

Conditions for queer people in Georgia during the 1990s was improving slowly, but there were still few legal protections available to the LGBTQ community. In 1997, the same year of the bombing, Atlanta officially recognized the domestic partnerships of same-sex couples after the case went all the way to Georgia Supreme Court. But the state would enact a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage in 2004 before things genuinely began to improve for LGBTQ Georgians.

At least while at the Otherside Lounge, gays, lesbians, bisexuals, and transgender people could worry less about the political climate and just be themselves. They were all out at their favorite lesbian bar, and they were safe – until the bombing.

Night of the Otherside Lounge Bombing & Aftermath

On February 21, 1997, a projectile bomb exploded on the back patio of the Otherside Lounge as a busy Friday night crowd enjoyed their night. When the blast went off, customers originally thought a fellow patron named Memrie Wells-Creswell had been shot. But when she revealed a spike nail sticking out of her arm, the crowd quickly realized a bomb had gone off.

Five people were injured in the blast, one with serious injuries. With over 100 people inside the Otherside Lounge at the time of the explosion, it’s astounding that more people were not seriously harmed in this domestic terror attack. When Atlanta police arrived at the scene of the bombing, they found a second bomb in a backpack in the nightclub’s parking lot and detonated it safely.

When the bomb exploded, McMahon was walking toward the front entrance of her bar. Shards of glass and other dangerous debris flew directly over her head and destroyed multiple cars in the parking lot. Her car’s backseat was completely blown out, including her two kids’ car seats.

Ford had just returned home from Otherside when the blast went off, missing the explosion by minutes. When she raced back, she watched firefighters triage a woman by the bar’s entrance. With doors and windows blown out, the interior of the Otherside Lounge was a wreckage of shattered glass, metal shrapnel, and dust.

The handful of customers harmed by the blast recovered from their injuries. But some faced social consequences after being outed as victims of the blast. when Atlanta Mayor Bill Campbell used Memrie Wells-Creswell’s name in a subsequent press conference, she was fired from her real estate job for being gay. She sued the company, but lost because there were no laws in Georgia that prohibited LGBTQ discrimination at the time.

More stories: Why Zazu Nova’s Legacy at Stonewall Deserves More Recognition

More stories: Why Do Bisexual Women Face High Rates of Sexual Assault?

More stories: Crystal LaBeija: Iconic Drag Queen Who Transformed Queer Culture

Otherside Lounge Owners Refuse to Back Down

In the aftermath of the Otherside Lounge bombing, bar owners Beverly McMahon and Dana Ford faced a barrage of threats from the newfound publicity. An onslaught of rape and death threats in letters and phone calls targeted them and their queer female customers in the days and weeks after the terrorist attack. The pair even considered sending their kids to Florida for their safety, but ultimately decided against it.

However, McMahon and Ford did decide to clear out the debris and shrapnel, pay for some remodeling work, and re-open the Otherside Lounge one week after the bombing.

Some regulars returned to their favorite Atlanta gay bar, but many did not. Unfortunately, the bar never saw the same crowds it did before the bombing. In addition to the loss of revenue, the owners of the Otherside Lounge faced nearly 20 lawsuits leveled against their nightclub, as some patrons argued that McMahon should have prepared for the bombing. McMahon and Ford won every lawsuit, but legal costs began to add up.

With lawsuits, renovation costs, loss of cash flow, and insurance delays, the pair was forced to shut down the Otherside Lounge in 1999.

Bomber Eric Rudolph’s Anti-Gay & Anti-Abortion Extremism

Video footage captured moments before a projectile bomb exploded at the Centennial Olympic Park in Atlanta on July 27, 1996. (Source)

Federal authorities immediately made connections with the Lounge bombing and other recent Atlanta bombings that put the entire city on edge. Seven months earlier, a bomb exploded at the Centennial Olympic Park during the Summer Olympic games, killing two people. And just one month before the Otherside bombing, seven people were injured in a bomb blast at a Sandy Springs abortion clinic. All explosives used in these attacks were projectile bombs, usually filled with nails and other metal shrapnel.

As the FBI scrambled to identify the bomber, they erroneously suspected a security guard named Richard Jewell before realizing the serial Atlanta bomber was a 29-year-old terrorist named Eric Robert Rudolph. Growing up in a deeply anti-Semitic household with his mother, Rudolph was heavily involved with the Christian Identity movement. This white supremacist belief system teaches that only white Christians can be saved from damnation. Illustrating the roots of his extremism, Rudolph even wrote an essay in 9th grade that argued the Holocaust never happened.

Eric Rudolph fostered extreme anti-gay and anti-abortion beliefs into adulthood, and chose those groups as targets of his terrorism. He found the Otherside Lounge in an Atlanta directory while looking for a local LGBTQ group to target next.

Nearly one year after the lesbian bar bombing, he bombed a Birmingham abortion clinic in what became the first fatal bombing of an abortion clinic in the U.S. Four months later, Rudolph was added to the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted List, where he remained for five years until his arrest in May 2003.

He confessed to four bombings in 2005: Olympic Park, Sandy Springs abortion clinic, Otherside Lounge, and the Birmingham abortion clinic. Rudolph was sentenced to life in prison at ADX Florence, a supermax federal prison in Colorado.

What the Otherside Lounge Means to LGBTQ Community Today

McMahon and Ford are still together, and their two kids are doing well. The pair miss the bar they owned together more than two decades ago, and they continue to receive mail from old customers, reminiscing about the old days and thanking them for operating a lesbian bar that meant so much to so many.

Ford says she is proud of what the Otherside Lounge represented to LGBTQ Atlantans: “I hope we made the impact with the community to empower and strengthen and be part of the fabric of the gay community … yes it was our savings; yes it was our retirement. But we’ve had two kids, we had a great life, and we have a great community around us.”

Today, there are a couple of lesbian bars in Atlanta, as well as many gay bars. Progress marches forward. But with the anti-LGBTQ actions of the previous presidential administration and a rise of white supremacist terrorism in 2021, safety for gays, lesbians, bisexuals, and transgender people is far from guaranteed.

It can be easy to forget that one of America’s largest mass shootings in history happened at a gay nightclub. But the 49 people killed in the Pulse Nightclub in Orlando in 2016 were targeted by the shooter because they identified as LGBTQ. Homophobic hate crimes in America are on the rise.

Holding onto strong community ties keeps us together and pushing progress forward. Looking out for one another is not optional. Because with the explicit rise of domestic terrorism in America in 2021, it’d be downright dangerous to believe the days of February 21, 1997, are long gone.

More stories: Crystal LaBeija: Iconic Drag Queen Who Transformed Queer Culture

More stories: Corporations Embolden Hate When They Cave to Anti-LGBTQ Fury

More stories: Dykes on Bikes & Gay Motorcycle Clubs in the U.S.

0 Comments