How Journalist Ruben Salazar Gave Voice to Chicanos in Los Angeles

Ruben Salazar was a journalist and civil rights advocate for the Chicano community in Los Angeles until he was killed by a sheriff’s deputy at the Chicano Moratorium on August 29, 1970. Salazar was sitting at a table inside the Silver Dollar Cafe when he died. (Source)

Updated September 15, 2024

October 12, 2023 ~ By Shari Rose

Ruben Salazar used his position as a journalist for the city’s largest newspaper to shed light on daily abuses faced by Mexican Americans and the Chicano Movement in Los Angeles

As one of just a handful of Latino journalists working in Los Angeles at the time, Ruben Salazar wrote on behalf of thousands of Mexican Americans who were marginalized and ignored in the city – and had been for generations. His years of writing about the needs, issues and injustices that so deeply affected the Chicano community made him a hero to many. And Salazar’s death at the hands of a Los Angeles sheriff’s deputy forever made him a symbol of Chicano pride and resistance against police brutality.

- Salazar’s Early Journalism Career

- Ruben Salazar Joins The Los Angeles Times

- Salazar Becomes a Foreign Correspondent

- Police Pay a Visit to the Journalist at Work

- LA Sheriff’s Deputy Kills Ruben Salazar at Chicano Moratorium

- Aftermath of Salazar’s Killing

- Legacy of Journalist Ruben Salazar in Los Angeles

Salazar’s Early Journalism Career

Ruben Salazar was born on March 3, 1928 in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. Before his first birthday, Salazar’s family moved and settled in El Paso, TX. After graduating high school, he served two years in the U.S. Army before attending Texas Western College.

Upon receiving his undergraduate degree in journalism, he worked as a reporter for the El Paso Herald-Post. As the first Latino journalist in that newsroom, Salazar quickly made a name for himself through his tenacity to get to the truth, particularly with regard to city government abuses and the overall treatment of marginalized groups.

Ruben Salazar with his mother in a family photo. (Source)

In May 1955, Salazar posed as an unhoused drunk to get police to arrest him and take him to El Paso Jail, a facility with a harsh reputation for cruelty against its inmates. There, he discovered outrageous human rights violations and documented them during his 25-hour stay. In the jail, which he coined “a chamber of horrors,” he uncovered shockingly unsanitary conditions for inmates, rampant drug use, and no medical attention for the sick and injured men jailed there.

“Tank 6 is a disgusting combination of live and inanimate filth,” he wrote in his 1955 story. “The men are systematically killing themselves: some with liquor, the rest with narcotics. The cells are like pigsties. There are two stinking toilets in the 22-foot-long tanks … The “cots” are thin slabs of interwoven steel strips attached to the walls.”

As a young reporter, Ruben Salazar was compelled to cover groups of people that wider society had abandoned and ignored. A few months after his prison stint, Salazar gained the trust of a well-known local drug dealer and conducted a long interview with her in her own home. His resulting story portrayed drug addicts as humans rather than animals, a purposeful act that very, very few reporters working for mainstream outlets were willing to do in the 1950s.

These two stories, wherein he fought to show the humanity of people that society had determined was unworthy of such a characterization, put Salazar on the FBI’s radar. The FBI would keep a file on the journalist for the next 15 years.

Ruben Salazar Joins the Los Angeles Times

Salazar carried on his work as a journalist, working for a small handful of newspapers in California before landing at the Los Angeles Times in 1959. He would continue to write stories for the paper until the day before he died in August 1970.

When Salazar joined the Times, the newsroom was nearly all-white. As one of the only Latino journalists in not just the newsroom but the entire city, he used his position to cover important issues affecting Mexican Americans in Los Angeles. His stories focused on the poorly funded schools their children attended, police brutality and racial profiling in “barrio” neighborhoods, and the lack of political representation at virtually all levels of city government – despite the large number of Latino residents living in the city.

- More stories: The Lack of U.S. Latino Representation in TV Shows & Films

- More stories: Cesar Antonio Rodriguez: Killed by Long Beach Police Over $1.75 Fare

- More stories: Police Killings of Latinos in Los Angeles: 2016 – 2021

During Ruben Salazar’s tenure throughout the 1960s, Mexican Americans sought a new social movement that intertwined with their heritage instead of burying it. After decades of believing that assimilation into white American culture would protect them from being treated as second-class citizens, many Latinos realized the fight for civil rights could not be won without community empowerment. Thus, the Chicano Movement was born.

Inspired in part by the Black Power movement, Chicanos rejected assimilation into Anglo-American culture and embraced their Mexican heritage in the fight against the systemic racism they experienced for generations since the Mexican-American War and beyond.

Throughout this period of social transformation, Ruben Salazar viewed himself as a journalist working for the Chicano community, accurately reporting on the obstacles they faced in Los Angeles. A few months before his death, he was asked how he could be both a reporter and an advocate for the people he covered.

Salazar holds his young child and points to the camera in an undated family video. (Source)

“I’m only advocating the Mexican American community, just like the general media is advocating, really, our economy, our country, our way of life,” he said in 1970. “So I’m just advocating a community within a community, which, by the way, the general community has totally ignored. And so, someone must advocate that, because it’s easy for the establishment to say, ‘Aren’t we all the same? Aren’t we all Americans?’ Well, obviously we’re not. Otherwise we wouldn’t be in the revolutionary process that we are in now.”

Salazar Becomes a Foreign Correspondent for the LA Times

In 1965, Salazar left Los Angeles to cover issues in the Dominican Republic, Mexico, and Vietnam during the war as a foreign correspondent. Throughout this period, the FBI investigated him at least 3 times while he was the Mexico City bureau chief, with a particular interest in the times he visited Cuba while covering stories for the paper.

Salazar (left) interviews civilians in Vietnam in 1965. (Source)

He came home to California in 1969 and continued to write for the Los Angeles Times as a weekly columnist. Upon his return, Ruben Salazar was confronted with a Chicano community at the height of its struggle for civil rights. East Los Angeles had become a focal point for Chicano activists and locals alike who demanded better school funding, an end to police brutality, more representation in city government, and a reckoning with the high number of Latinos killed in the Vietnam War.

As was the journalist’s style, Salazar didn’t shy away from the issues when he returned to LA. He covered school walkouts that called for more Chicano teachers, Border Patrol abuses against migrants, conflicts between young Chicano activists and older generations of Mexican Americans, California democrats who didn’t keep their promises to Latinos, police killings in the city, and more.

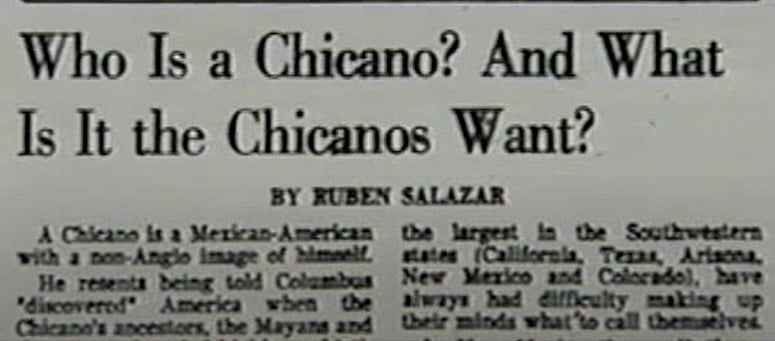

On February 6, 1970, Salazar wrote one of his most important columns, “Who Is a Chicano? And What Is It the Chicanos Want?”

Salazar’s famous column from February 1970, “Who Is a Chicano?” (Source)

Salazar writes in part: “Why, ask some Mexican-Americans, can’t we just call ourselves Americans? Chicanos are trying to explain why not. Mexican-Americans, though indigenous to the Southwest, are on the lowest rung scholastically, economically, socially and politically. Chicanos feel cheated. They want to effect change. Now.”

- More stories: Armando Garcia-Muro: Teenager Killed by LA Sheriffs as They Shot a Dog

- More stories: The Lives of Ferguson & Black Lives Matter Activists Cut Short

- More stories: Francisco Garcia: Killed by LASD Deputy Luke Liu in 2016

For the first time, Chicanos felt they had a person within the establishment who actually had their backs. Salazar gave Mexican Americans a voice in a city that had little interest in recognizing them as deserving of their full rights.

But despite all the support he gained from local Chicanos, Ruben Salazar knew that his writing was making enemies in the city, too. Specifically, the Los Angeles Police Department and Sheriff’s Office.

Salazar Fears for His Life After a Police Visit at Work

In January 1970, Salazar became the news director for Spanish-language station, KMEX, while maintaining his column for the LA Times. With the widespread access of a television audience, he could reach more people than ever, especially Mexican-Americans in the city. He explained his choice to switch to television in a May 13, 1970 interview.

“I wanted to really communicate with the people about whom I had been writing for so long,” he said. “And at the Times I was doing, I think, a job that had to be done, and that is, communicating with the establishment about our problems. But I wanted to try my hand at communicating with the Mexican-American community directly and in their language.”

A mural to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Chicago Moratorium and Salazar’s legacy in the city, taken on October 23, 2020 in Los Angeles. (Kirby Lee via AP)

As news director, he aggressively pursued stories that affected Latinos the most. When LAPD officers killed two Mexican nationals in July 1970, Salazar ran a piece on the television station about the deaths. The day after it aired, LAPD officers paid him a visit at the station. Salazar wrote about what they said to him in his July 24 column at the Los Angeles Times.

“They did not question my right to run the interviews but warned me about the ‘impact’ the interviews would have on the police department’s image,” he recounted. “Besides, they said, this kind of information could be dangerous in the minds of barrio people.”

Around the same time this piece aired, Salazar had been working on a massive story. He and other reporters at the station were uncovering and investigating widespread allegations that the LAPD and Sheriff’s Department were terrorizing Mexican-American neighborhoods by planting drugs, beating residents, and committing other abuses.

One of the reporters working on the story, William Restrepo, was informed by one of his sources that the LAPD had learned about this project. After hearing the news, Salazar grew concerned that police were following him. It was later confirmed by police records that the department had indeed created a file on Ruben Salazar. It contained some of his columns, transcripts from television broadcasts, and other biographical information about the journalist.

About 10 days before he was killed, Salazar called the Los Angeles office of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights and spoke to Charlie Ericksen, a commission staffer and one of his friends. He told Ericksen that he wanted it on an official record that he suspected police were shadowing him.

Ruben Salazar with his wife and children in an undated photo. (Source)

Three days before he was killed, Salazar told a small group of friends while sitting in a Mexican restaurant that he feared the police were going to kill him. These men included Ericksen, Commission on Civil Rights Western Regional Director Philip Montez, and a Catholic priest named Henry Casso. In a later interview, Montez said Salazar was very concerned about what the police might try to do to him.

“I had never seen him as upset as he was,” Montez said. “He had a feeling they were going to kill him.”

LA Sheriff’s Deputy Kills Journalist Ruben Salazar at Chicano Moratorium

On August 29, 1970, an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 people came together in East Los Angeles to protest the disproportionate number of Mexican-American soldiers killed in the Vietnam War. A widely sourced 1969 study conducted by Ralph Guzman at the University of Santa Cruz found that war casualties with Spanish surnames were documented at 19%, but the Spanish surname population of the Southwest accounted for only 11.8% at this time. This stark discrepancy proved a catalyst for one of the largest anti-war demonstrations taken by a singular ethnic group in the U.S.

Photograph of Mexican-American marines who served in Vietnam. (Source)

Known as the National Chicano Moratorium Against the Vietnam War, this day-long demonstration brought thousands of Latinos from Los Angeles and around the nation into the city. Salazar and his television crew were on the scene first thing in the morning.

The Chicano Moratorium was a peaceful event until word of a looting taking place at a liquor store caught the attention of police. Wearing riot gear and wielding batons, Los Angeles sheriffs determined they would clear the park where crowds had gathered. They fired tear gas canisters into the audience, causing a panic among attendees.

Los Angeles police using tear gas and batons against demonstrators at the Chicano Moratorium on August 29, 1970. (Source)

Ruben Salazar and his crew stayed to capture footage of people running for cover, some throwing tear gas canisters back at police, and others being beaten by police. After some time, they retreated from the action and went to a nearby bar called the Silver Dollar Cafe.

- More stories: Melyda Corado: Trader Joe’s Employee Killed After LAPD Fired Into Store

- More stories: Echoes of Slave Patrols in ICE Raids: What Abolitionists Can Teach Us

- More stories: How Isaac Wright Jr Overturned Life Sentence & Became a Lawyer

One of the reporters in that crew was William Restrepo, who worked with Salazar on the police brutality project that caught the LAPD’s attention the month prior. He said in a later interview that deputies followed him and Salazar as they walked to the bar.

Los Angeles cop in riot gear beats a Chicano protester with his baton in video footage captured by local television crews. (Source)

Around 5pm, Los Angeles sheriff’s deputies surrounded the Silver Dollar Cafe. Witnesses and bar patrons who testified at a later inquest say that deputies never commanded them to exit the building. Rather, they say that a deputy pointed his shotgun at four men and ordered them back into the bar. Though police deny this happened, one witness across the street took a photo of this deputy holding men at gunpoint by the bar’s front door as two women behind him pleaded for him to stop.

Standing less than 5 feet from the doorway, Deputy Thomas H. Wilson fired two tear gas canisters into the one-story building. As he sat at a table across from Restrepo and sipped a beer, Salazar was struck in the head by one of these canisters and killed instantly. He left behind his wife, Sally, and their 3 young children.

Deputies left Salazar in the building for more than 2 hours before homicide detectives finally examined his body. In all, police killed 3 people that day at the Chicano Moratorium: 15-year-old Lynn Ward, 35-year-old Angel Diaz, and 42-year-old Ruben Salazar.

Aftermath of Salazar’s Killing

In the days after his killing, Angelenos were deeply suspicious that Salazar was murdered by law enforcement as retaliation for his coverage of their abuses against Mexican Americans.

During a 16-day inquest conducted by the city’s coroner’s office, investigators sought to determine what happened on August 29. However, it quickly devolved into a media spectacle. Half a dozen television stations covered the proceedings, and anti-Mexican rhetoric dictated much of the inquest. Chicano activists denounced the proceedings as nothing more than an opportunity for law enforcement to classify Latinos as a violent, dangerous class in need of aggressive policing.

A member of the media stands in front of the painting “The Death of Ruben Salazar” by artist Frank Romero during a press tour of the “Our America: The Latino Presence in America Art” exhibit in October 2013, at the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

One week after the inquest concluded, the district attorney declined to file manslaughter charges against Deputy Wilson or any officer who was there that day. The family of Ruben Salazar filed a lawsuit against Los Angeles County and won a $700,000 settlement.

A U.S. House Representative for the state of California, Rep. Edward Roybal, wrote a letter to the Justice Department to ask for an impartial probe to examine if the well-known journalist was targeted. The Justice Department later said that it conducted an investigation in March 1971 and found insufficient evidence to file charges in Salazar’s killing. However, those close to Salazar said they were not aware that federal officials were involved in any investigation, as they say they were never spoken to as part of that investigation.

The LA Sheriff’s deputy who killed Salazar, Thomas Wilson, examines a tear gas gun used at the Silver Dollar Cafe while on the stand during the Ruben Salazar inquest on September 29, 1970. (Source)

In 2011, the Los Angeles County Office of Independent Review revisited the Salazar case and determined that there was insufficient evidence that he was intentionally killed. Regardless of whether he was targeted or simply in the wrong place at the wrong time, the loss of Salazar’s voice was a devastating blow to the community he loved.

Legacy of Journalist Ruben Salazar in Los Angeles

As one of the only Latino journalists in a city where its largest minority group was massively underrepresented and powerless, he became an important voice for millions of Mexican Americans in Los Angeles and throughout the nation. In a reality where poverty ran rampant, educational opportunities were cut off, and police officers roamed neighborhoods looking for their next target, Mexican Americans had someone in their corner who brought to light the daily abuses they were forced to contend with every day.

Demonstrators march post a billboard with image of journalist Ruben Salazar during a Chicano National Day of Action rally to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Chicano Moratorium on August 29, 2020 on Whittier Blvd. in Los Angeles. (Kirby Lee via AP)

It’s no wonder that the park off Whittier Boulevard where protesters met for the Chicano Moratorium was later named after him, today called Ruben Salazar Park. There’s also the Ruben Salazar Journalism Awards, which are awarded to reporters and photographers who “demonstrates journalism excellence while contributing to a better understanding of the Latino communities by portraying Latinos fairly and accurately.”

Ruben Salazar Park in Los Angeles features a mural commemorating the Chicano Movement and Salazar himself. (Source)

Salazar rose to prominence in a majority-white, highly educated, even elitist institution. But instead of turning a blind eye toward his community, he brought their fears, dreams, obstacles, and hopes to the forefront of his work. He held onto his progressive roots and reported truthfully on a marginalized identity that no major outlets had an interest in covering. It’s quite impossible to count the number of doors Ruben Salazar opened for generations of Latinos who came after him, myself included.

- More stories: How Stetson Kennedy Infiltrated the KKK & Changed the Jim Crow South

- More stories: Book Banning in the U.S. at an All-Time High

- More stories: Aztec Architecture: Floating Gardens & Aqueducts in Tenochtitlan

0 Comments