How a Retractable Syringe Exposed Powerful Group Purchasing Organizations in U.S. Healthcare

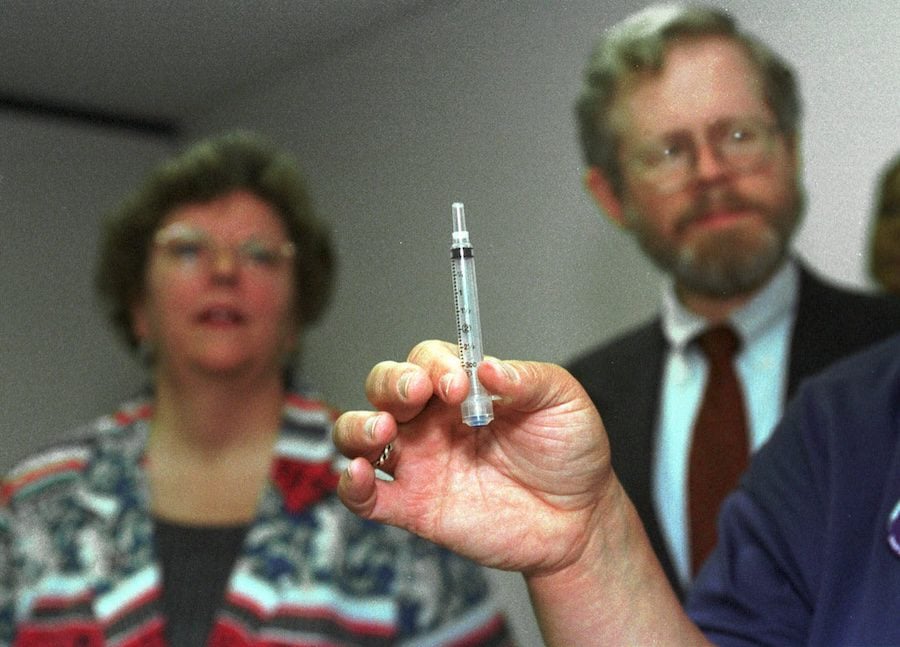

A safety syringe with a retractable needle is demonstrated at a news conference in Albany, NY in 1999. (AP Photo/Tim Roske)

February 1, 2025 ~ By Shari Rose

Thomas Shaw’s invention of a safety syringe to prevent needlestick injuries uncovered the monopolistic power of GPOs in the medical supply chain, rife with cover-ups, derailed investigations and mysterious deaths of prosecutors in 2004

In the U.S. healthcare system, an opaque but powerful collection of middlemen known as group purchasing organizations (GPOs) control hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of medical supply purchases each year. Backed by a system of legally sanctioned kickbacks and exclusive contracts that would be illegal in any other industry, GPOs enjoy monopolistic influence over hospital supplies that affects the life of each and every American.

When an engineer named Thomas Shaw invented a safer retractable syringe that could prevent thousands of accidental needle sticks among healthcare workers during the AIDS epidemic, he inadvertently started a chain of events that would include two federal prosecutors found dead, three more suddenly fired, eight U.S. Attorneys forced to resign and a series of investigations that reached the highest levels of the Justice Department. The events surrounding something so innocuous as a safety needle exposed how easily for-profit group purchasing organizations can choose to protect their billion-dollar interests at the expense of making new life-saving technologies accessible in U.S. hospitals.

- Thomas Shaw Invents the Retractable Syringe

- GPOs Refuse to Adopt Safety Syringes that Prevent Needlestick Injuries

- Shaw Approaches Attorneys Mike Weiss & Paul Danziger

- AG’s Office in Texas Investigates Novation in 2004

- Two Federal Prosecutors Investigating GPOs Die Suddenly

- U.S. AG Alberto Gonzales Fires Eight U.S. Attorneys Investigating Healthcare Fraud

- Why Group Purchasing Organizations Are Too Powerful to Reform

Thomas Shaw Invents the Retractable Syringe

In the late 1980s, Thomas Shaw owned a small engineering business in Lewisville, TX that performed civil engineering projects in the area. As he was watching television one night, a news special about a doctor in California who had contracted HIV after accidentally getting stuck by a needle piqued his interest.

The story stuck with Shaw, who had a friend recently diagnosed with AIDS. He set out to build a safer syringe that addressed this problem the very next day. It soon became an obsession of his, and after four years and 150 versions of his design, Shaw invented the first retractable syringe. It was a revolutionary invention. With a retractable needle that automatically snapped back into the barrel after use, Shaw created a safety syringe that made accidental sticks virtually impossible.

The National Institutes of Health recognized his invention’s potential immediately, and gave Thomas Shaw a $650,000 grant in 1993 to miniaturize the design and produce 50,000 units for clinical trials. By the mid 1990s, Shaw had raised $42 million, largely from doctors at Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas who wanted to use this technology in their facility. With this new funding, he established Retractable Technologies in Little Elm, TX and got to work.

In 1996, Shaw conducted a final round of clinical trials for his retractable syringe. Medical professionals who tested his safer needle syringes were ecstatic at the invention, and it seemed like a slam dunk for protecting healthcare workers from needle sticks not just in Texas, but across the U.S.

Thomas Shaw’s invention did more than keep medical professionals safer in the workplace. It also unearthed pervasive corruption in America’s medical supply system that had an interest in prioritizing profits over life-saving innovation. Though he had solved the engineering challenge of building a safer syringe, he would encounter a far more formidable obstacle. That is, the enigmatic business practices that controlled nearly every medical purchase made for U.S. hospitals by group purchasing organizations.

GPOs Refuse to Adopt Safety Syringes that Prevent Needlestick Injuries

Group purchasing organizations are intensely powerful companies that control product purchasing for most of America’s hospitals. By 2005, two GPOs known as Novation and Premier controlled more than 50% of all hospital purchases made in the country.

How did we get here? This system began in the 1970s with a common purpose: allowing hospitals to negotiate lower prices from medical supply companies. GPOs began as nonprofits, funded and managed by the hospitals themselves. But a minor change to a Medicare law in 1986 would fundamentally change this system into a colossal, for-profit venture.

Section 9321 of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1986 exempts GPOs from Medicare’s anti-kickback provisions so that they can collect “fees” from medical suppliers in exchange for contracts. This created a new incentive for GPOs. Instead of working to secure the lowest prices for hospitals, GPOs’ revenues became tied to the profits of the healthcare supply companies they were supposed to be negotiating against.

- More stories: America Has the Highest Maternal Mortality Rate Among Western Nations

- More stories: Wheelchairs & Airlines: Why Is Flying So Risky for Those With Disabilities?

- More stories: Martha Mitchell Was Right About Watergate

When Thomas Shaw tried to sell his retractable syringes in 1997, he discovered the implications of this law firsthand. Despite the clear safety advantages of his product and strong support from medical professionals, he couldn’t even get his foot in the door. That was because hospitals were locked into contracts with group purchasing organizations that required them to purchase from established manufacturers like Becton Dickinson, which controlled 90% of the syringe market at the time.

When Novation finally agreed to take a look at Shaw’s retractable needle syringes, they wanted to mark up his $0.27 bid to $1 per unit, sell under their “Novaplus” label and pocket those massive profits for themselves. Shaw called this what it was: Nothing more than thinly veiled demands for kickbacks for a medical device that would save lives, made all the more egregious during the height of the AIDS epidemic.

The Novation logo outside of the headquarters of VHA, Inc., the parent company of Novation and Provista, in Texas. (Photo by Kristoffer Tripplaar)

“If you pay anybody any fee, administrative or otherwise, to try to influence a purchase, that would put you in prison in any other industry,” he said in an interview with Fort Worth Weekly.

In essence, Americans’ taxes had funded the development of Shaw’s retractable syringes through NIH grants, and the very system designed to provide hospitals with the best medical supplies was now preventing that same technology from protecting healthcare workers.

And with each passing year that his safety needles were not used in hospitals, more doctors and nurses continued to suffer needless sticks from inferior devices, exposing themselves to HIV, hepatitis and other deadly conditions.

With no other avenues to pursue that would get his safety syringe needle on the market, Thomas Shaw made the choice to challenge the entire medical supply system and sue the group purchasing organizations themselves.

Shaw Approaches Attorneys Mike Weiss & Paul Danziger

In 1998, Shaw met with lawyers Michael David Weiss and Paul Danziger. Weiss had already established himself as an attorney willing to take on politically charged cases. He represented several clients in political causes and had co-chaired two successful whistleblower cases. Along with Danziger, his law partner and long-time friend from high school, Weiss saw the opportunity to shed light on this systemic corruption and put an end to some of the healthcare industry’s worst impulses.

Undated photo of Mike Weiss, attorney who represented Thomas Shaw in the safety syringe case before his sudden death in October 1999. The 2011 movie, Puncture, is based on his life. (Source)

The evidence was certainly on their side. Despite holding patents on superior syringe technology and offering to match competitors’ prices, Retractable Technologies had been effectively locked out of the market.

Weiss and Danziger filed a federal antitrust lawsuit against Becton Dickinson, Novation, Tyco and Premier. The lawsuit targeted how group purchasing organizations had morphed from purchasing agents working for hospitals into sales organizations that worked for manufacturers. Through “administrative fees” and other imposed costs, the GPOs were providing market share to powerful manufacturers in exchange for payments that would be illegal in any other industry.

A sign shows the Becton Dickinson logo at the GPO’s facility in Sparks, MD. (Kristoffer Tripplaar/ Sipa USA)

But these were massive monopolies that Mike Weiss, Paul Danziger and Thomas Shaw were going toe-to-toe with in the safety syringe case. Becton Dickinson had a revenue of $4.5 billion in 2003, while Retractable Technologies’ sales were just $19 million annually.

They were David going against Goliath, but tragedy struck before the case went to trial. Mike Weiss passed away on October 2, 1999, at just 32 years old. The official cause of death was a drug overdose, and authorities did not pursue further investigation. As a former judicial clerk for Judge Edith Jones, his memorial service was held at the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals federal courthouse in Houston.

Despite Weiss’ death, the retractable syringe lawsuit moved forward. It eventually led to an array of settlements, first with Novation, Premier and Tyco in April 2003, and later a $100 million settlement with Becton Dickinson in July 2004. In an interview with Washington Monthly, Shaw lamented that these settlements did less to reform the system than to keep its inner workings hidden from public scrutiny.

“The group purchasing organizations that were BD’s agents paid us $50 million to keep their practices from being reviewed in front of a jury,” he said in 2010. “Either they’ve got minimal trust in the average juror or they’ve got something they don’t want the public to know.”

AG’s Office in Texas Investigates Novation in 2004

In the aftermath of the safety needle lawsuit, federal prosecutors in Dallas launched what should have been a landmark investigation into group purchasing organizations and the medical supply industry in August 2004. They honed in on Novation, but the implications of this probe threatened to unearth decades of systematic manipulation by GPOs in the U.S.

The investigation’s scope was sweeping. Federal officials issued subpoenas to Novation, various hospitals and major manufacturers like Becton Dickinson. At its core, investigators sought evidence of Medicare fraud and conspiracy to defraud the United States.

- More stories: How Ruben Salazar Gave Voice to Chicanos Until He Was Killed by Police

- More stories: How Cassie Chadwick Pulled One of the Greatest Bank Heists of the Gilded Age

- More stories: Why Have School Portables Become Permanent Classrooms?

As one source close to the investigation explained to Fort Worth Weekly, “Hospitals get a big fat check once or twice a year from the GPOs. No other deal gives free money to a hospital. And they can report checks not as a reduction in cost, but as miscellaneous income. This allows them to be reimbursed … for the original price before they account for the money they get from GPOs and manufacturers. That’s what the investigation is about.”

Under criminal chief for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Dallas, Shannon K. Ross, the investigation gained momentum. Once she signed subpoenas, the New York Times published an article called “Wide U.S. Inquiry Into Purchasing For Health Care” on August 21, 2004. It seemed the investigation would finally expose the corrupt web of financial arrangements that had long protected the GPO system from meaningful reform.

Then the investigators started dying.

Two Federal Prosecutors Investigating GPOs Die Suddenly

Thelma Quince Colbert, assistant U.S. Attorney and the office’s lead prosecutor for Medicare fraud, was found dead in her swimming pool on July 20, 2004. She had been preparing the subpoenas against group purchasing organizations before she died, the same ones that Shannon Ross ultimately signed. Colbert was 54 years old and had served as assistant U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Texas for 14 years. This district covers some 8 million people with main offices in Dallas, Fort Worth, Lubbock and more.

Less than two months after Colbert’s mysterious death, 44-year-old Shannon Ross was found dead in her home on September 13, just weeks after signing those subpoenas that Colbert was working on before she died.

Similarly to Mike Weiss’ death in the lead up to the safety syringe case, authorities quickly dismissed both these women’s deaths and did not investigate further. Colbert, who was found face down in her own pool, was deemed to have died by accidental drowning by the Tarrant County Medical Examiner’s Office. Ross, who had no known life-threatening health issues, was determined to have died suddenly of meningomyeloradiculitis.

One month after Shannon Ross’ death, three other prosecutors from the Fort Worth office, Assistant U.S. Attorneys Michael Uhl, Leonard Senerote and Michael Snipes, were inexplicably fired. All three had connections to recent subpoenas issued by their office in the investigation of Novation and other group purchasing organizations for anti-competitive practices.

Former U.S. Attorney Michael Snipes was the lead prosecutor in the 2018 trial of a police officer who killed an unarmed 15-year-old. The officer was found guilty and sentenced to 15 years in prison. (Rose Baca/The Dallas Morning News via AP, Pool)

In five months, five federal prosecutors involved in investigating medical supply companies had died or been terminated from their positions. The federal probe that had promised to bring to light systemic healthcare fraud in the U.S. was effectively dismantled.

With evidence of sweeping interference and cover-ups with federal investigations growing louder, questions about who exactly was protecting this multi-billion dollar industry would point to the most-senior positions in the Department of Justice.

U.S. AG Alberto Gonzales Fires Eight U.S. Attorneys Investigating Healthcare Fraud

On January 9, 2006, the chief of staff for Attorney General Alberto Gonzales produced a list of eight U.S. Attorneys who were to be fired. Among them was Todd P. Graves of Missouri, whose office had been actively investigating Medicare fraud and specifically focused on the financial relationships among medical supply companies, GPOs and hospitals.

Gonzales used a little-known provision of the Patriot Act to remove these prosecutors and replace them with loyal appointees without term limits, all without Senate confirmation.

Alberto Gonzales appears before the Senate Judiciary Committee during his confirmation hearing for U.S. Attorney General on January 6, 2005. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

The impact on ongoing GPO investigations was immediate. In Missouri, Graves was replaced by Bradley Schlozman, whose office then killed investigations into public corruption cases related to the medical supply chain litigation.

- More stories: Israel Has Killed Record-Breaking Numbers of Journalists & Aid Workers

- More stories: How Isaac Wright Jr Overturned Life Sentence & Became a Lawyer

- More stories: Police Killings of Unarmed Latinos in Los Angeles, 2016 – 2021

By January 2007, national outrage at the mass U.S. Attorney firings and misuse of the Patriot Act had become too loud to ignore. In an attempt to quell the mounting scandal, Attorney Alberto General Gonzales announced that John Wood would replace Schlozman. But the damage was already done. Investigations into group purchasing organizations and medical supply companies had been effectively ended, and the prosecutors with decades of experience who were investigating this corruption were gone.

Former U.S. Attorney Todd Graves testifies before the Senate Judiciary Committee in Washington on June 5, 2007. (AP Photo/Lawrence Jackson)

Gonzales’ removal of Todd Graves in particular sent a clear message to other prosecutors about the risks of investigating certain types of healthcare fraud: Pursuing cases against entrenched medical suppliers and their GPO partners could be career-ending, perhaps in more ways than one.

Why Group Purchasing Organizations Are Too Powerful to Reform

The story of Thomas Shaw’s retractable syringe tells us more than just about the struggle of one inventor to get his medical device on the market. It exposes the relationship between group purchasing organizations and medical supply companies that is so monopolized it can neutralize any threat to its control, even at the highest levels of the American legal system.

In 2012, just five GPOs controlled an estimated $130 billion in medical supplies. But the real measure of their power is found in their ability to control a system that can work against the interests of patients and healthcare workers in favor of ever-growing profits.

Despite creating a demonstrably safer syringe that prevents thousands of accidental needle sticks and quite literally saves lives, Shaw was locked out of hospitals by GPO contracts that required purchasing from established manufacturers. Even when he offered to match competitors’ prices, his life-saving product remained largely unused.

And in the face of congressional hearings, media exposés and multiple lawsuits, the structure of this system remains firm. That 1986 Medicare law exemption that allows GPOs to collect fees from medical supply companies, known as kickbacks in any other industry, is still in effect today, continuing to legitimize mark-ups on medical supplies like safety needles and encourage prioritization of profits over safety.

Companies that represent group purchasing organizations, such as the Healthcare Supply Chain Association, release periodic reports about how much money GPOs save the healthcare industry. One such report from 2019 declares that “GPOs Save Healthcare System, Medicare & Medicaid, Taxpayers Up to $34.1 Billion Annually.” However, these numbers are largely based on surveys from hospital administrators rather than hard numerical data. And those hospitals typically base their figures on the discounts they get off list prices provided by GPOs themselves.

According to a 2003 supply chain study by Lynn James Everard, most hospital managers only know how much their GPOs based on information given to them by those same GPOs: “Hospitals know the prices they get through their GPOs but have little or no idea of what the cost to the supply chain is of having GPOs in the picture,” the report found.

Until this system undergoes lasting reform, Americans will continue to pay twice. First in higher healthcare costs and again in lost innovations gobbled up by a system that has a history of gatekeeping potentially life-saving inventions like the safety syringe needle simply because they cost pennies more to purchase.

Thomas Shaw’s patented retractable needle syringe survived and remains in use in hospitals across the U.S. today, but it took years and years of legal battles to make it so. How many other potentially world-changing healthcare inventions were lost to America’s powerful group purchasing organizations? We will truly never know.

- More stories: The Forgotten Anti-Filipino Watsonville Riots of 1930

- More stories: Riot Dogs: El Vaquita & Loukanikos Who Joined Protesters Against Police

- More stories: Book Banning in the U.S. at an All-Time High

- More stories: Hatpin Panic: How Hat Pins Upended 20th Century Gender Politics

0 Comments