Jovita Idár’s Fight for Mexican-American Rights in Texas

Jovita Idár meets with members of the Union Stone Mason and Bricklayers in Laredo, TX in 1915. (Source)

October 30, 2021 ~ By Shari Rose

Through journalism and activism, Jovita Idár dedicated her life to fighting against anti-Mexican discrimination in Texas

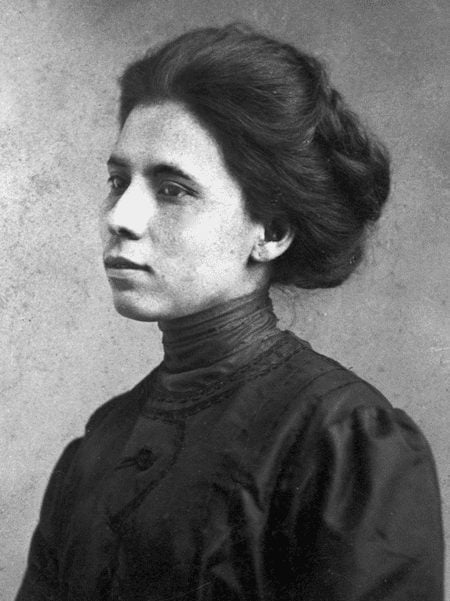

Jovita Idár in a 1905 portrait. (Source)

Jovita Idár was born in Laredo, TX on September 7, 1885. The second of eight children born to Jovita and Nicasio Idár, young Jovita grew up in a family that actively fought for the civil rights of Mexican-Americans in Texas. As the editor of the Spanish-language newspaper, La Crónica, Nicasio was a leading advocate for the rights of Tejanos living near the Mexican border and consistently denounced anti-Mexican violence in the state. This combination of activism and journalism would set Jovita on a path for the rest of her life.

As a child, Jovita Idár received her education at Methodist schools in South Texas. She attended the Laredo Seminary (now known as the Holding Institute), and received a teaching certificate at age 18. Idár moved to Los Ojuelos to teach young Mexican-American children at a segregated school. However, she was disheartened to find the school extremely underfunded, with a lack of books and education materials.

Idár wanted to improve the conditions she saw for Mexican-Americans, and she soon realized she could make a bigger impact through journalism. So, she ended her young teaching career and began writing for La Crónica, joining her father and two brothers at the paper.

Jovita Idár Begins Writing at La Crónica

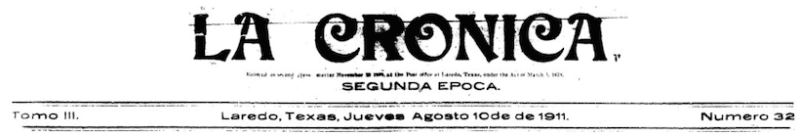

La Crónica focused exclusively on the interests of Mexican-Americans and Tejanos at the border. Though the terms are often used interchangeably, Tejanos are Latinos who descended from Spanish settlers and settled in Northern Mexican states before that land became part of Texas in 1845.

Known today as “Juan Crow” laws, the same Jim Crow principles that allowed for legal dscrimination, abuse, and killings of Black Americans were levied against Mexican-Americans. Lynchings and mob violence were commonplace, Tejano children were segregated into poorer schools, and speaking Spanish in public was prohibited.

Advocating for the rights of these Mexican-Americans was dangerous work in southern Texas, but the Idár family did not hold back. Jovita and her brothers wrote extensively about systemic racism, and covered stories that English-speaking newspapers would not, such as the 1911 lynching of a 14-year-old Mexican-American boy named Antonio Gómez.

An old discriminatory sign from a Texas business, now at the National Civl Rights Museum, that reads, “No Dogs, Negores, Mexicans.” (Source)

Jovita Idár believed in empowering Latinos on both sides of the border, and pushed for for a cultural nationalism of sorts. Regardless of citizenship, Idár believed that all people of Mexican descent had the same mutual interests and could unite under similar ideas. She, and the Idár family as a whole, understood that no government or municipal organization in Texas would lend help to Mexican-Americans. So, they would have to help one another.

- More stories: How Ruben Salazar Gave Voice to Chicanos Before He Was Killed by Police

- More stories: Police Shootings of Latinos in Los Angeles Since 2016

- More stories: How the Hatpin Panic Changed 20th Century Gender Politics

Idár wrote about many of the issues and obstacles facing Tejanos and Mexicans alike, but a major target of her journalistic career was the role of education in the state. Idár advocated for bilingual education in schools, lifting segregated schools out of poverty with proper funding, and rejecting the growing Anglo-American influence in education.

Idár believed that education was the key to raising Mexican-Americans out of extreme poverty and giving them the tools to participate in local politics. Because she was a woman, Jovita Idár wrote with a pen name her entire life. Her two most common pseudonyms were “Ave Negra,” meaning black bird in Spanish, and “Astrea,” the Greek goddess of justice.

The masthead of La Crónica newspaper in 1911. (Source)

El Primer Congreso Mexicanista of 1911

Jovita Idár and her family members at La Crónica proposed creating the El Primer Congreso Mexicanista (the First Mexican Congress) in Laredo to organize local leaders and produce ideas for improving conditions for Mexican Americans. They reached out to local journalists, Mexican mutual aid groups (called sociedades mutualistas), and other organizations that worked to support Tejanos and Mexicans on both sides of the border.

Both men and women were active participants in El Primer Congreso Mexicanista, which was very, very uncommon for the time. Politics and public life was almost exclusively reserved for men, but this event was different. The convention officially kicked off on September 14, 1911, and lasted for one week. Congressional representatives chose Nicasio Idár to lead the Gran Liga, and Jovita was elected president of the Liga Femenil Mexicanista (League of Mexican Women).

The Liga Femenil Mexicanista was both a political and charitable association. Its motto was simple: “Pro la Raza y Para la Raza” (By the People and For the People).

With Jovita Idár at the helm, the Liga leaned into heavy feminist influences, and worked to empower women to join the feminist movement. It encouraged women to be financially independent from men and to broaden their opportunities outside the home. The organization raised funds for families in need, created bilingual schools that were free to students, and created programs that supported women of Mexican heritage.

After the Primer Congreso Mexicanista ended, Idár founded El Estudiante (The Student). This publication provided strategies for Tejano teachers to implement bilingual education, formulate their own lesson plans, and push back against the growing influence of Anglo-American culture in Mexican-American schools.

In an article Jovita Idár wrote for La Crónica titled “For the Race: Mexican Children in Texas,” she called for Tejano educators and families to educate Mexican-American children on their own:

“Mexican children in Texas need an education. There is no other means to do it but ourselves, so that we are not devalued and humiliated by the strangers who surround us.”

Anti-Mexican Killings During La Matanza

The Mexican Revolution, which began in 1910, forced many to flee the growing threat of violence in Mexico and head for Texas. The influx of Mexican refugees into Texas as well as white residents’ fear of Mexican seditionists led to large-scale anti-Mexican killings, which became known as La Matanza (The Slaughter).

The first person to die during La Matanza in Texas was Antonio Rodriguez, a 20-year-old farmworker. In November 1910, he was accused of murdering a white woman. One day after he was arrested, a mob of white men removed him from his cell and burned him at the stake. No one was ever arrested in his killing.

- More stories: How Cassie Chadwick Pulled One of the Greatest Bank Heists of the Gilded Age

- More stories: Aztec Architecture: Floating Gardens & Aqueducts in Tenochtitlan

- More stories: California’s History of Anti-Asian Laws and Riots

In June 1911, 14-year-old Antonio Gómez walked past a small group of white men while whittling a piece of wood with a knife in the small Texas town of Thorndale. The men grew angry at the trail of wood shavings he left behind, and a German-American named Charles Ziechang attacked Gómez and attempted to grab his knife. The teenager stabbed Ziechang in the chest and was soon arrested.

Word quickly spread that a Mexican-American teenager killed a white man, and a mob of dozens white men formed. Within three hours of the stabbing, the mob removed Gómez from the jail and lynched the 14-year-old. Eventually, four men were tried for murder, but all were aqcuitted or had their charges dropped.

In 1915, Texas massively increased its police budget and hired even more Texas Rangers at the border, including a new force of “Loyalty Rangers” who were specially appointed by the governor to prevent Mexican-Americans from taking part in civil liberties, such as voting. As a result, the summer of 1915 was particularly brutal, with hundreds of anti-Mexican killings carried out by Texas Rangers and white civilians alike. This particular period of violence became known as the Hora de Sangre (Hour of Blood) in Mexico, and was perpetuated by mostly law enforcement officials.

Because the killings of Mexican-Americans by police and white mobs were rarely reported on by mainstream, English-speaking newspapers, we will never truly know how many people were murdered in this rampage. But historians estimate that between several hundred and 5,000 Mexican Americans were killed by Texas Rangers and white mobs between 1910 and 1920.

Jovita Idár Faces the Texas Rangers

In the midst of this racial violence and terror against Tejanos at the hands of law enforcement and private citizens alike, Jovita Idár was undeterred. She continued to write about the atrocities she saw and advocated for the rights of Mexican-Americans.

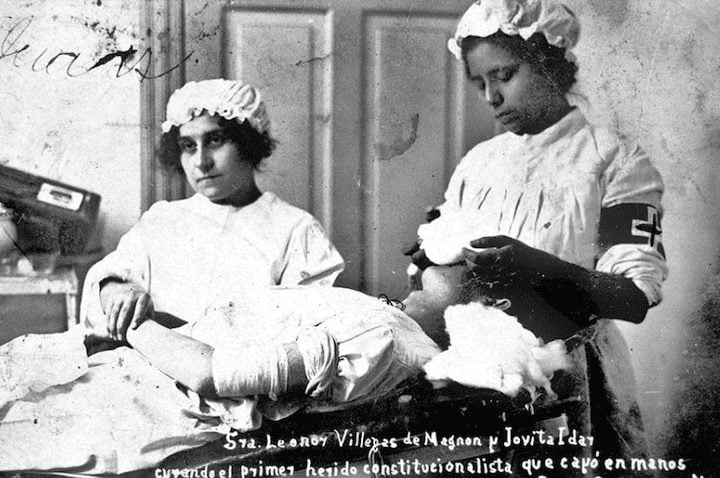

After working as a volunteer nurse for La Cruz Blanca (White Cross) in Mexico during the revolution in 1913, Jovita Idár returned to Laredo. She joined the staff of El Progreso, a local newspaper. Similarly to La Crónica, El Progreso covered stories and topics related to the interests of both Tejanos and Mexicans.

Jovita Idár and Leonor Villegas de Magnón volunteer as nurses with La Cruz Blanca during the Mexican Revolution in 1913. (Source)

In 1914, El Progreso published an op-ed from a writer named Manuel García Vigil. The piece criticized President Woodrow Wilson’s decision to send American soldiers to the border. Outraged by the editorial, the Texas Rangers quickly formed a plan to destroy El Progreso entirely. However, Jovita Idár was in the newsroom when they arrived to tear it down.

Alone, Idár met the group of Texas Rangers at the front door of the building and refused to let them in. Eventually, the men decided to leave.

True to form, the Texas Rangers returned to the building the following day when Idár was gone and destroyed the newsroom. They stole items from offices, obliterated the newspaper’s printing presses, and arrested reporters.

According to one of Jovita’s brothers, Aquilino, the Texas Rangers found García Vigil and attempted to lynch him. Their father heard the news and contacted a friend, who was a local judge. At the behest of Nicasio Idár, District Judge John Mullally ordered that Vigil be released from police custody and sent to hospital, saving his life.

Idár Returns to La Crónica

Jovita Idár stands next to printing presses with other staff members of El Progreso in 1914. (Source)

Soon after the destruction of El Progreso by Texas law enforcement, Nicasio Idár died of an intestinal disorder in April 1914. Jovita and two of her brothers, Federico and Clemente, took over La Crónica. As both journalists and editors, the Idárs continued to support the mission of the paper, whose tagline read, “We work for the progress and the industrial, moral and intellectual development of the Mexican inhabitants of Texas.”

Eventually both Jovita and Clemente moved on to different newspapers in their careers, and even established one together, called Evolución. This newspaper was established in Laredo, but had devoted readers throughout Texas, Mexico, and Cuba.

In 1917, Idár married Bartolo Jaurez, and the couple soon moved to San Antonio. They quickly founded the Democratic Club, and became active political figures in the community as leaders in the Democratic Party.

Idár helped create a free kindergarten for young students and worked as a translator for Spanish-speaking patients at the Robert B. Green Memorial Hospital in San Antonio. She also became an editor for El Heraldo Cristiano, a Spanish-language publication associated with the Methodist Church.

At the age of 60, Jovita Idár Juárez died on June 15, 1946 of a pulmonary hemorrhage, caused by complications from tuberculosis. She is buried at San Jose Burial Park in San Antonio.

Mexican-American Education in Texas Schools

Up until 2018, K-12 schools in Texas did not provide a Mexican-American studies course to students. In a state that is 39% Latino, its school system did not provide a single course in its public schools that directly related to that population until 2018. Furthermore, it took four years of intense fighting and lobbying to finally get the Texas State Board of Education to incorporate a single Mexican-American studies (MAS) course. To this day, there is still no official textbook for the MAS course in Texas.

The fight that Jovita Idár dedicated her life to is far from over. But maybe, as a small but growing number of students in Texas learn about her fight for the political, social, and economic advancement of Mexican-Americans in Texas, they’ll realize this struggle was always here, and it continues to this day.

- More stories: The Lack of U.S. Latino Representation in TV Shows & Films

- More stories: Yuri Kochiyama at the Intersection of Black Power & Asian Movements

- More stories: Prison Gerrymandering Is A Modern 3/5 Compromise

- More stories: Echoes of Slave Patrols in ICE Raids: What Abolitionists Can Teach Us

0 Comments