The Economic Power of a Spinster

Women working in a piecework factory in 1909. (Source)

By Shari Rose ~ February 29, 2020

At their core, spinsters, also called old maids or thornbacks, were single women who rejected the expectations set forth by Progressive Era society

A 1891 portrait of a young woman. (Source)

A spinster, as defined by the stereotype, is a term used to describe an unmarried woman without children. Typically believed to be an elderly, bitter and overall unhappy woman, a spinster supports herself economically and does not rely on a man. The origin of ‘spinster’ has been used since the Middle Ages and was used to describe the profession of a woman who spun yarn. Over time, it became an insult to essentially represent a woman past her prime.

However, the spinster, also called an old maid, or thornback, was on top of her game before the rest of society even realized she was playing. The independence from social restraints that inevitably came with a husband and children around the beginning of the 20th century was extremely attractive to many women at this time.

Women’s Options in the Progressive Era

Though it eventually garnered a negative reputation, to be a single, unmarried woman free from the responsibilities of a husband and children in the late 19th century to turn of the 20th century was very attractive to many young women. Lifestyle options for women in the U.S. were extremely limited: even the right to vote was years away. The ability to make decisions for one’s own life typically wasn’t possible for women in the strict convention and traditions of the time.

The alternative to being a dutiful wife and doting mother was to live the single life and support oneself as a spinster in a world that offered few professional opportunities to women. However, as cities and urban areas continued to develop, jobs in factories and the education industry opened to single women in the years following the Civil War.

Unmarried Women Flock to Factories

Until the 1870s or so, it was uncommon to see women working in factories. However, when opportunities to make a living outside the home presented themselves, young women all over the country jumped at the chance to get their foot in the door.

The job itself was usually piecemeal work, meaning each employee would receive a small sum for each piece completed. When it came to determining a factory woman’s earnings, experience on the job was key. A woman’s wages would grow with her experience on the job, incentivizing loyalty to the factory and staying in the workforce for as long as possible.

More stories: How School Portables Became Permanent Classrooms

More stories: Whitewashing in Hollywood: 2000 – 2019

For young women in particular, there were significant financial advantages to entering the workforce early that ultimately outweighed race, age and other potential detriments to a decent wage. Unlike today, race and ethnicity did not play a significant role in a factory woman’s earnings. While immigrant factory workers on average earned 9% less than their native-born coworkers when first beginning their careers, research has found that is due to foreign-born workers entering the workforce at a younger age. Both American-born and non-American-born factory women made the same amount of money once “relative maturity is considered.”

Ironically, the reason we know so much about women’s earnings is because female economic independence was quite the controversial subject in society from the mid-1800s to early 1900s. Thus, civic institutions of the time collected as much data as possible concerning the professional choices of young, unmarried women in an effort to create laws that curb female independence and spinsterhood, particularly when it was perceived that their choices were encroaching on men’s employment.

Spinster Teachers in Schools

Before social tides changed and spinsters were regarded with suspicion by much of mainstream society, unmarried women were actually preferred by many schools as teachers because it was believed they would not split their allegiance to their school and their husband.

Federation of Colored Women’s Club of Jacksonville in 1915. (Source)

These single school teachers were so prevalent in school districts that housing was built to accommodate them specifically, such as boarding houses and women’s apartments. Without the social responsibilities of husbands and children, teachers hired during this wave found new opportunities to socialize with other like-minded teachers, choose to remain single, and otherwise live their lives by their own terms.

More Stories: Why the Hat Pin Panic Never Ended

However, schools did not expect these young women to be satisfied with the single way of life and remain unmarried for the years to come. They comfortably believed teachers would work for a few years and then marry. It was even assumed that these education jobs would help prepare women for motherhood. But as these women continued to delay or reject husbands and children in favor of their careers and singlehood, society at large grew more and more concerned. In a world where women were submissive to men, the notion of women rejecting this submission even in their private lives was very threatening to the traditional power structure.

Society Responds to Spinsters, Thornbacks, and Old Maids

While these women first found employment precisely because they were single, spinsters came under increasing scrutiny and suspicion, and were eventually vilified for their choices. At the turn of the 20th century, there was an explosion of “scientific research” on human sexuality that with heavy overtones of religious influence. As one may expect, well-respected institutions began to argue that women who do not marry and procreate should be shamed, questioned and even treated for pathological disorders. Furthermore, accusations involving spinsters’ sexuality and their personal motives reached a fever pitch in some areas of the country.

And as common belief turned against the idea of female economic independence, “spinster” grew in popularity as a negative label used to describe a single, childless woman believed to be lonely, bitter, unhappy, and so forth.

As social mores changed, so did public perception of these single women earning their own money and supporting themselves without depending on a man. By existing outside of their conventional roles – childbearing, married women who stayed in the home – they became “gender transgressors.” That is, women who found joy and fulfillment in their professions, in their singlehood, in their lives at large. Thus, “spinster”, “thornback”, “old maid” , and more evolved into insults to wield against women who had other goals and other dreams than the mainstream would willingly allow.

Why Did Many Young Women Favor Spinsterhood in the Progressive Era?

Despite backlash they experienced, scores of women freely chose spinsterhood. Some pointed to the professional opportunities it provided, others simply had no interest in marriage because they did not meet a man who met their standards. Other women pointed to how marriage did not seem “worth pursuing to the detriment of their often benevolent vocations.”

While common belief held that single women led wasted and undignified lives, those who chose to remain single argued for their own sovereignty, that is, the right to live as one pleases.

Catharine Sedgwick, American author and spinster. (Source)

Catharine Sedgwick, American novelist of the 19th century, wrote in a letter about her choice to remain single: ” We raise our voice with all our might against the miserable cant that matrimony is essential to the feebler sex – that a woman’s single life must be useless and undignified – that she is but an adjunct to man … we believe she has an independent power to shape her own course and to force her own separate sovereign way.”

Sedgwick contends that a full and purposeful life does not require a man, and furthermore, women have the power to determine the path their lives will take. She went on to write a large body of work during the course of her life that depicts domestic life in the U.S.

Another woman in the same period, named Emily Howland, spent her 20s wondering when she would find something that gives her purpose. At age 31, she wrote to her mother: “May I give a little of my life to degraded humanity? … May I try if I really can to make the world a little better for having lived in it? Can’t thee spare me a while to do what I think of my portion? I want to do something which seems to me worth of life, and if all my is to go on as have the last ten years, I know I shall feel at the of it as tho’ I had lived in vain.”

Aware of the social restraints that came with a husband and children, Howland was not satisfied with the options that life would give her. Similar to other spinsters and single women of her time, she weighed the options and chose a different path.

Many of these spinsters wanted their lives to mean something different than what was expected of them. Their goals and aspirations did not fall within the realm of the domestic home. This deviance from the norm had social consequences, but they knew it would be worth the chance to live life the way they chose. And many of these spinsters went to accomplish incredible things in their lives. Some famous thornbacks of the 19th and 20th centuries include Jane Austen, Louisa May Alcott, Emily Dickinson, and Susan B. Anthony to name just a few.

Modern-Day Spinster Movement

Spinsterhood, also called ‘singlehood by choice’ or an array of other options, is on the rise in the U.S. in the 21st century. In addition to recent social developments, such as the “childfree” movement, choosing the single life is vastly more accepted and supported in modern times. Though, that isn’t to say that women who are single by choice don’t continue to face social backlash and consistent suspicion from others.

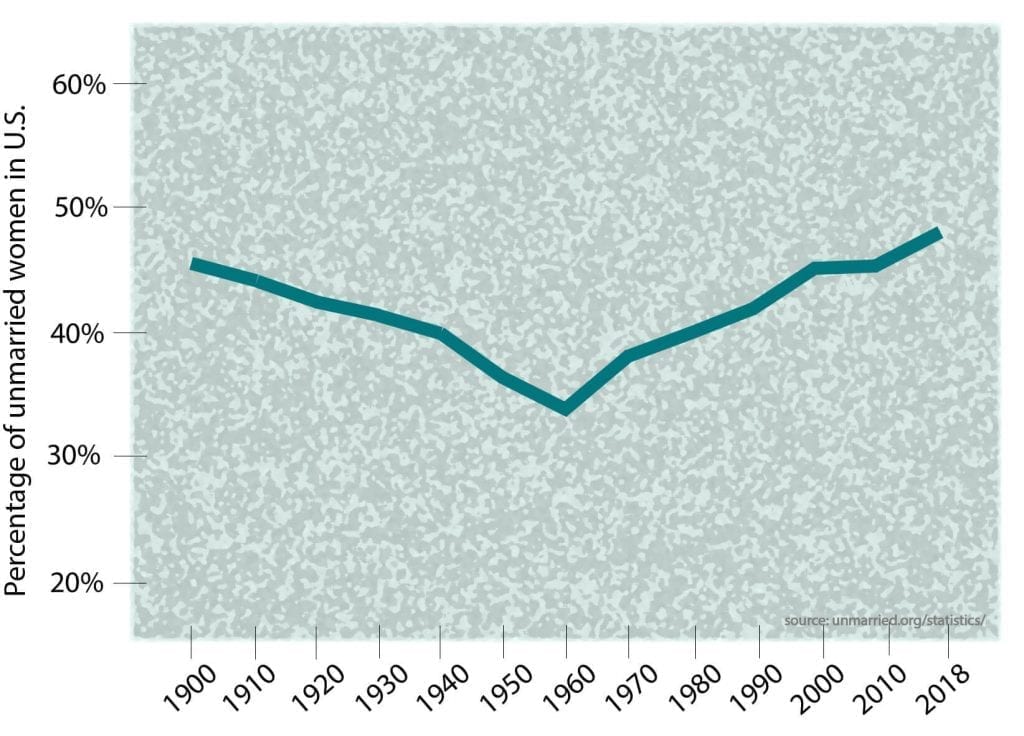

Graph displaying percentages of unmarried women in the U.S. (Source)

Have the arguments against the single, childfree woman changed much in the last 100 or so years? Not a whole lot. It is still a common belief that women are sad, lonely, or flawed if they remain unmarried and without children in their lives. Take a look at nearly any movie involving a single woman as the protagonist in the last 50 years. Her story is not complete and “happily ever after” until she meets a man and settles down. That’s when the story can end and we can leave the theater.

But social restraints be damned, women today have the ability and the right to live the life they please. And while perhaps the notion of a strong, independent woman is still considered a relative new social development, women 200 years ago in this country were running the same kind of hustle, well before they even had the right to vote.

From Condoleezza Rice to Coco Chanel and beyond, modern spinsters, old maids and thornbacks are in good company. At the end of the day, our modern-day spinster can look like a lot of different people in different stages in life, but one thing remains the same: spinsters are going to live their lives precisely how they want, with or without society’s approval.

Share this story

|

|

|

|

|

|

The real issues regarding the idea of the sovereign individual vs. the social restraints of society are yet to be fleshed out as it is expressed in this article. What exactly does it mean to be a sovereign individual against the backdrop of the social restraints of society? While it is abhorrent to think that an individual should not live the life they please, it is not clear how far the boundaries of those social restraints go. To what extent is a meaningful, long-lasting relationship as well as having children something that we as a society should praise or not praise? To me, it doesn’t seem reasonable to disavow the biological premise of having a healthy and functional family in order to live a life that is meaningful in a way that I choose. Yet, for some reason the ingrained biological need to procreate and have a stable family is somehow perceived as being a “social restraint”.