John Mitchell Jr.’s Relentless Fight For Justice At The Richmond Planet

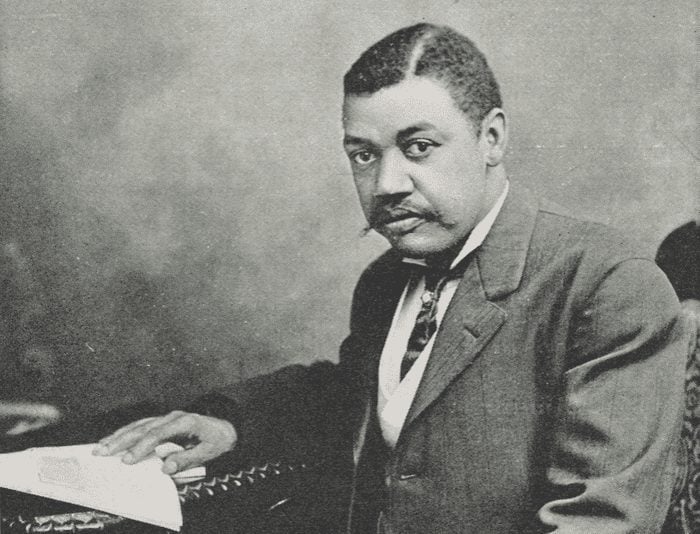

John Mitchell Jr. at The Richmond Planet in 1917. (Source)

January 17, 2022 ~ By Shari Rose

Editor of The Richmond Planet, John Mitchell Jr., fought to uncover and condemn racial injustice against Black Virginians at all levels of Southern society

As editor of The Richmond Planet, John Mitchell Jr. fought against systemic injustice levied upon Black Americans in Virginia, and sought to create economic opportunities to help lift them out of poverty. His relentless resistance against Jim Crow laws and mob lynchings in the form of the written word as well as direct action on the street made The Richmond Planet of the most influential Black newspapers of the post-Reconstruction era.

Mitchell’s Early Life

John Mitchell Jr. was born on July 11, 1863, just one week after the Battle of Gettysburg ended. Born a slave in an area outside Richmond, Mitchell lived with his parents and younger brother on the estate of James Lyons, a wealthy Southern lawyer who often hosted Jefferson Davis and other Confederate generals at his mansion. Mitchell became a carriage boy for Lyons, as the aristocrat refused to allow the 10-year-old boy to attend school. However, Mitchell’s mother taught him how to read and sent him to school when he was 13 years old.

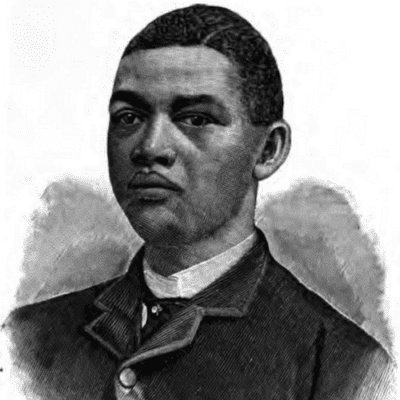

John Mitchell Jr. in 1887. (Source)

Mitchell attended Richmond Normal High School. While at school, he had a talent for drawing maps and won multiple statewide awards for his work in his late teens. His maps were so impressive that Mitchell soon became an apprentice at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in Washington, D.C., and local leaders started to take notice.

When Mitchell was 18 years old, Frederick Douglass wrote about his work in a letter to a friend: “I am glad to have the evidence of the talent and skill afforded in the map of Virginia by your young friend, John Mitchell Jr., with the industry, patience and perseverance which he has shown in this work, I have no fear that young Mitchell will make his way into the world and be a credit to our race.”

Mitchell graduated valedictorian and returned to Richmond Normal High School as a teacher. He taught for nearly three years until the newly elected Richmond school board fired all Black teachers and principals at the school, in a situation not unlike the current conservative outrage over “critical race theory” erupting at local school boards today.

One of the few Black newspapers in Virginia, The Richmond Planet, published a strongly worded editorial condemning the firings of Black educators. Founded by 13 former slaves in 1882, The Richmond Planet was a trusted weekly newspaper for Black Americans that covered city, state, and national news with a focus on issues important to the Black community.

After Mitchell lost his teaching job, he remained in Richmond and began writing articles for nearby newspapers before turning to the Planet. At the age of 21, Mitchell became editor of The Richmond Planet in December 1884, just two years after the paper’s founding. He would remain the paper’s editor for the next 45 years.

- More stories: The Fate of Margaret Morgan in Prigg v. Pennsylvania

- More stories: Marshall Sherman’s Capture of Virginia Battle Flag at Gettysburg

- More stories: Martha Mitchell Was Right About Watergate

John Mitchell Jr. At The Richmond Planet

As the paper’s leader, Mitchell spent much of his time covering racial injustice and anti-Black violence in Virginia. In the pages of The Richmond Planet, he railed against Jim Crow laws, segregation, lynchings of both Black and white Americans, and the resurgence of white supremacy after the Reconstruction era.

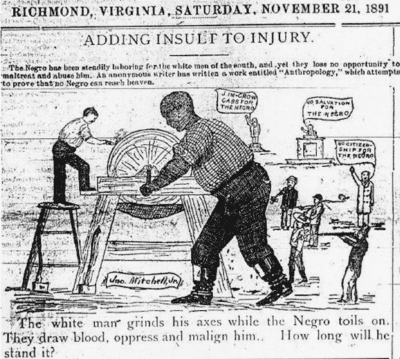

An editorial cartoon by Mitchell from 1891 that denounces racial injustice against Black Americans. (Source)

As a gifted writer and cartoonist, he crafted editorials and political cartoons that lambasted the Ku Klux Klan and terror of racial violence that white newspapers largely ignored. In May 1886, after a Black man named Richard Walker was lynched by a white mob in Charlotte County, Mitchell responded with a scorching editorial in The Richmond Planet. He received multiple death threats, including a rope and letter sent to his office, which informed him he would be next to hang. Undeterred, John Mitchell Jr. printed the death threat in the newspaper and responded to it with a paraphrase from Shakespeare.

“There are no terrors, Cassius, in your threats, for I am armed so strong in honesty that they pass me by like the idle winds, which I respect not,” he wrote.

But Mitchell wasn’t finished yet. Wearing a pair of revolvers, he walked to the scene of the lynching in Charlotte County and went to the jail where Walker was held before the mob took him. He later reported that none of the locals came to confront him, including the writer of the death threat.

John Mitchell Jr., The “Fighting Negro Editor”

Mitchell’s intrepid and often confrontational style in the face of racial injustice soon lent him a nickname that stuck for the rest of his life: the “Fighting Negro Editor.” As described in a February 1887 edition of the New York World, “One of the most daring and vigorous Negro editors is John Mitchell Jr., editor of The Richmond Planet. The fact that he is a Negro and lives in Richmond does not prevent him from being courageous almost to a fault.”

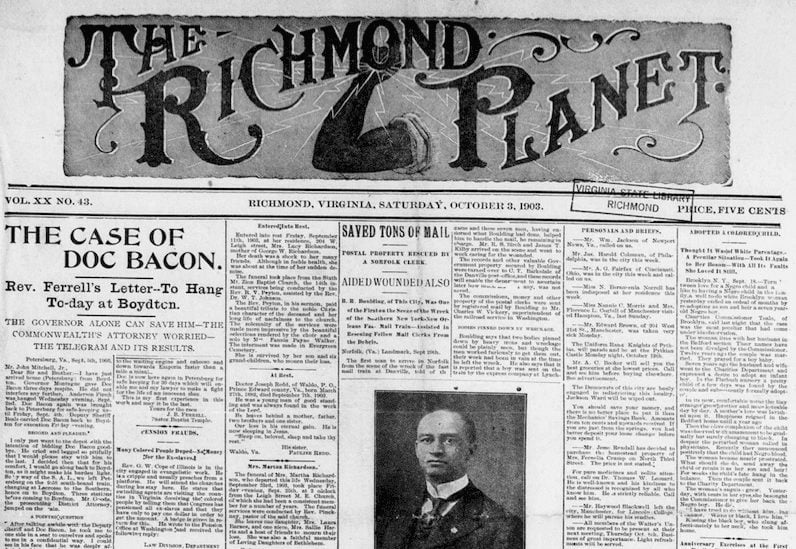

Front page of The Richmond Planet, taken from October 3, 1903. (Source)

In May 1889, a 15-year-old Black youth named Simon Walker was arrested and accused of raping a 12-year-old white girl. Though the jury had no evidence, they found him guilty and asked for the death penalty, which the judge granted. The case was hardly covered in the white press, but Mitchell spotted a notice about the case in one of the papers and decided to act.

Mitchell later wrote that the execution of a teenager by the state would be a “disgrace.” He said, “It was not a case of race or color, it was one of humanity.” He went straight to Virginia Gov. Fitzhugh Lee to request a stay of execution. Gov. Lee, nephew of Robert E. Lee, was vacationing in Dagger’s Spring, so Mitchell travelled hundreds of miles to speak with him. He successfully convinced the governor to delay the execution for 30 days.

As the execution date loomed, Mitchell again met with Gov. Lee at his Richmond mansion, but found that Lee was no longer interested in what he had to say. Instead, John Mitchell Jr. worked with Walker’s court-appointed lawyer and they secured another stay of execution the night before the teenager was to be hanged.

Moreover, Mitchell needed to share the news with the local sheriff before dawn or it would be too late. He borrowed a horse and carriage from some friends and raced to the Chesterfield courthouse, delivering the stay of execution in the early morning hours of Walker’s execution day. Mitchell then spoke with Walker in his jail cell, and described in the Planet the poor conditions of the jail, and the sadness of the 15-year-old sentenced to die.

He drew editorial cartoons of the gallows he saw outside the jail as well as the coffin waiting for Walker, which helped to garner support among Black Americans to reduce Walker’s sentence. Eventually, Mitchell successfully persuaded authorities to reduce the 15-year-old’s sentence, and he was not executed by the state.

- More stories: Jovita Idár’s Fight for Mexican-American Rights in Texas

- More stories: Israel Has Killed a Record Number of Journalists & Aid Workers in 6 Months

- More stories: Esther Jones: Betty Boop’s Original Influence

Mitchell Enters Virginia Politics

In 1892, Mitchell was elected to represent Jackson Ward on Richmond’s Board of Aldermen, or City Council. He was re-elected two years later. However, he lost his seat in 1896 during what he called the “Jackson Ward Robbery.” No Black candidates won election anywhere in the city as hundreds of ballots cast by Black voters were tossed out by election officials. In The Richmond Planet, Mitchell called the election “nothing more nor less than a farce.”

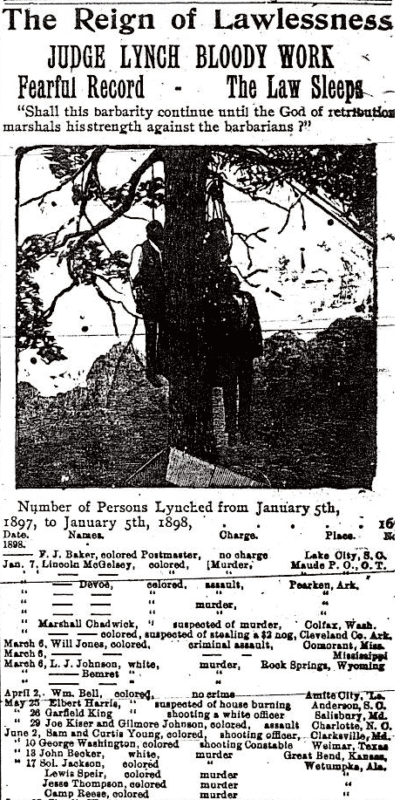

A list of lynching victims in 1897, written by John Mitchell Jr. in The Richmond Planet. (Source)

In spite of the disenfranchisement of Black voters, Mitchell continued to be involved in civic leadership. He was elected president of National Afro-American Press Association in 1894 and became the leader of the state’s chapter of the Knights of Pythias some years later.

In 1902, John Mitchell Jr. spoke at the Virginia Baptist State Convention, saying in part, “I am for Negro enterprises, and for that reason, some have attempted to consign me to the hot region to feast on fire and brimstone.”

“There is a principle involved in this, and I am for that principle,” he said. “We have a mission, and that mission will be to help build up these Negro enterprises, to help foster the work the National Baptist Publishing Board which is furnishing literature for our boys and girls in the Sunday schools.”

Despite his foray into local politics, Mitchell remained committed to The Richmond Planet. As lynchings of Black Americans reached its peak in the 1890s, Mitchell faithfully printed lists of names and locations of lynching victims throughout the decade. By 1896, circulation of The Richmond Planet reached 6,400, though many more read the paper each week. Copies were shared with family members, friends, and co-workers.

The influence of The Richmond Planet reached beyond the city, attracting readers throughout the state and beyond. Each week, Mitchell sent a copy of the newspaper to the governor’s mansion as well as to many of Richmond’s white editors of daily newspapers.

Mitchell’s Fight For The Return Of Solomon Marable’s Body

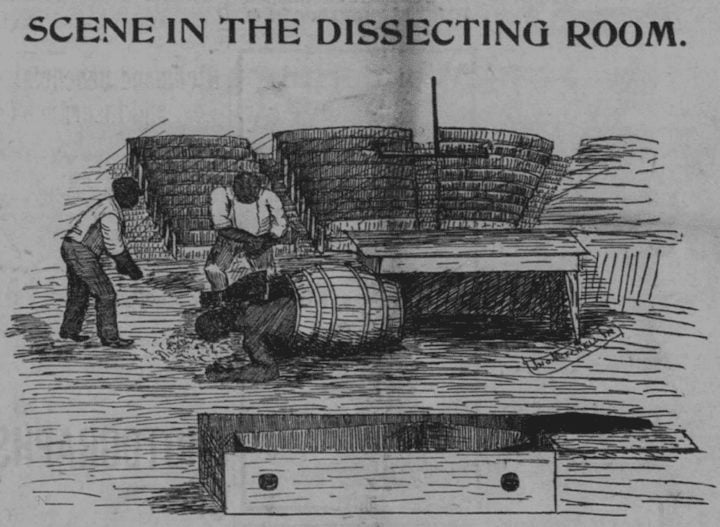

After a Black man named Solomon Marable was hanged at the gallows in 1896, his body was not returned to his wife for burial. Instead, it was shipped to the Medical College of Virginia for dissection by students against his family’s wishes. John Mitchell Jr. and others from the paper, as well as Black religious leaders from the area, went to the location where Marable’s body was kept.

In the middle of the night, they descended upon the building and demanded to see his remains. They were shocked to find Marable’s body stuffed haphazardly into a barrel.

“It was a ghastly sight,” wrote Mitchell in The Richmond Planet. “The like of which we hope never to see again.”

An editorial cartoon drawn by Mitchell in an 1896 edition of The Richmond Planet that shows the body of Solomon Marable left in a barrel. (Source)

Due to the efforts of Mitchell and local Black leaders, Marable’s body was washed, placed back into his coffin, and sent back to his wife and children in North Carolina.

“Humanity had triumphed. Science had given away in the face of plainer demands of reason and the dictates of commonsense. The pledge made at the gallows was fulfilled at the grave,” wrote Mitchell.

Mechanics Savings Bank & Mitchell’s Run for Governor

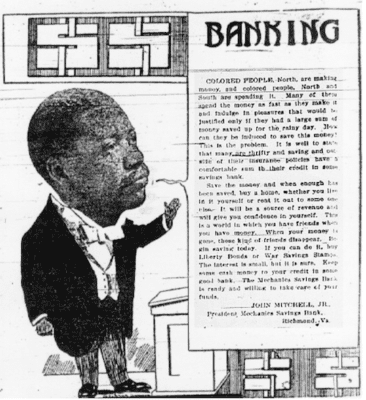

After witnessing Black disenfranchisement at the ballot box at the end of the 1890s, John Mitchell Jr. turned to economic enterprise as a way to lift African Americans out of poverty. In 1902, he founded the Mechanics Savings Bank to be a place for Black Virginians to safely store and save their money. Eight years later, he erected the bank’s new home on the corner of Clay Street and Third, a four-story building replete with marble in the lobby and top-of-the-line security features.

An advertisement for Mechanics Savings Bank appears in The Richmond Planet. (Source)

In an advertisement for the Mechanics Savings Bank, Mitchell wrote, “We have installed the Burroughs Adding Machine Equipment of book-keeping. It’s the most up-to-date system in use. We have a 33-ton steel vault with a 9 ton round steel door. We have 500 safety deposit boxes in which you can keep your money, jewelry, deeds, wills, insurance papers, and the like.”

At the peak of its popularity in 1919, the Mechanics Savings Bank held more than $500,000 in deposits.

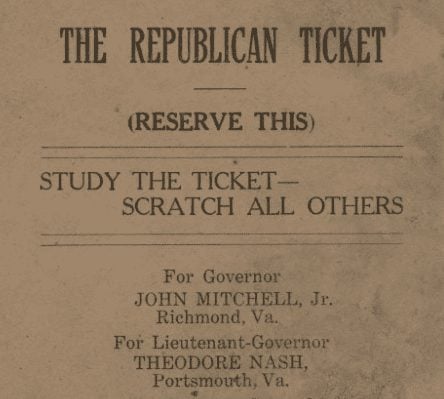

In 1921, John Mitchell Jr. announced his candidacy for governor of Virginia on the Republican ticket. However, the state’s Republican Party, which was largely progressive at this time, had been losing elections for years. Resentful whites would not vote for this party of Lincoln, and conservative Democrats had successfully prevented huge swaths of Black Americans from voting in previous elections at the turn of the century.

- More stories: Book Banning in the U.S. at an All-Time High

- More stories: Reckless Eyeballing: How Matt Ingram’s Story Reveals Fear of Black Sexuality

- More stories: Lucy Hicks Anderson: Black Transgender Pioneer of the 1940s

White supremacist rhetoric condemned Republicans for being “the party of the Negro,” and it worked. In response, Republicans in Virginia decided to run on a Lily White ticket, that is, an all-white group of candidates. In 1921, Republicans barred Black delegates from their state conventions and removed any inclusion of racial justice from their official party platform.

A 1921 political flyer for the all-Black Republican ticket that lists Mitchell as the candidate for Virginia governor. (Source)

Consequently, hundreds of Black delegates met in Richmond and nominated their own candidates for office. They chose Mitchell as their candidate for governor of Virginia. Known derisively as the Lily Black ticket, these candidates ran against both the Lily White Republicans and Democrats in the state. Ultimately, the Republican Party lost in a landslide and Democrats swept the state. Over the next couple decades, Black voters would largely abandon the Republican platform and join the Democrats as the party’s support for civil rights and racial justice moved to the forefront.

The State Charges Mitchell With Bank Fraud

After Mitchell lost the election, he continued to run The Richmond Planet and the Mechanics Savings Bank. One year after Mitchell’s bid for governor, the state of Virginia accused him of misusing tens of thousands of dollars in bank funds. His bank shut down the same year. In the newspaper, Mitchell wrote a passionate plea of innocence and asked for support from the community as he fought the charges.

“We solemnly swear no, as we swore upon the witness stand, that not one dollar of our forty-five years’ accumulation has been the result of dishonorable actions or sharp practices,” Mitchell wrote in May 1923.

In 1923, John Mitchell Jr. was found guilty of bank fraud and sentenced to three years in prison. However, he fought for his appeal, taking his case all the way to the state’s Supreme Court of Appeals. The court overturned his conviction and he was cleared of all charges. But despite his exoneration, the damage was already done.

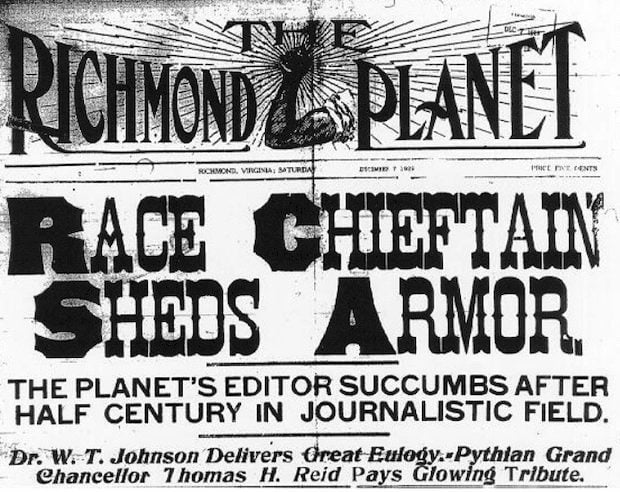

The bank went into receivership and was rechartered by the state of Virginia in 1924. His assets lost and reputation diminished, Mitchell was left broke though he was cleared of any wrongdoing. He later wrote that he believed the state targeted him in retribution because he ran for governor. Mitchell continued to lead The Richmond Planet until his death, where he collapsed at his desk and died in December 1929. He was 66 years old.

The death of John Mitchell Jr. is covered above the fold in The Richmond Planet. (Source)

The Richmond Planet was bought and renamed in 1938, and continued publishing until 1996. Despite Mitchell’s larger-than-life influence in Virginia, his legacy in Virginian history was largely cast aside until recent years. Some groups, like the National Digital Newspaper Program, have worked to preserve his life’s work at The Richmond Planet. You can now browse many decades’ worth of clippings from the Planet during John Mitchell Jr.’s tenure as editor.

0 Comments