How Stetson Kennedy Infiltrated the KKK & Changed the Jim Crow South

Left: Stetson Kennedy leaves the U.S. Capitol building in Klan attire on Sept. 10, 1947 (AP Photo). Right: Kennedy attends the Florida Heritage Gala where he was inducted into the Florida Artists Hall of Fame on April 6, 2005, in Tallahassee. (AP Photo/Steve Cannon)

May 15, 2025 ~ By Brooke Pland

In 1946, Stetson Kennedy infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan to share insider information with journalists and the FBI in an effort to take down the KKK from the inside

A Florida native who began his career as a writer, Stetson Kennedy is perhaps best known for his successful infiltration of the Ku Klux Klan. Kennedy’s experiences inside the group allowed him to feed valuable information about the Klan’s membership and political movements to authorities and journalists, playing a crucial role in the dismantling of the group throughout the Deep South and earning him the nickname, “Klan Buster.”

Considered both a “pioneering Florida folklorist and social activist” and “a man the Klan would rather forget,” Kennedy left an indelible mark on both the United States and the world at large for his decades-long career championing racial equity and dismantling discriminatory systems in the Jim Crow South.

- Kennedy’s Upbringing in the Jim Crow South

- Stetson Kennedy Infiltrates the Ku Klux Klan

- Life After the Klan

- Later Activism Work and Published Books

- The Legacy of Stetson Kennedy in a Racially Divided America

Kennedy’s Upbringing in the Jim Crow South

Born William Stetson Kennedy to a wealthy Jacksonville family in 1916, Kennedy’s life was shaped by growing up in the Jim Crow South. His grandfather had been an officer in the Confederate Army, and his mother helped lead the local Daughters of the Confederacy group. As a child, Kennedy helped his father’s furniture store by going door-to-door to collect customers’ weekly $1 payments toward their purchases – an experience which quickly revealed to him the intense racial and socioeconomic disparities of his own community.

“During months spent trying to pose as a hard-boiled bill collector, seeking payments on furniture accounts from impoverished Southern whites and Negroes during the depths of the depression, I became acutely aware of one-third of the nation,” Kennedy said two decades later. “No sooner was I aware of their problems than I determined to do something about them… I would write a book telling how the multitudes suffer from lack of food, clothing, shelter.”

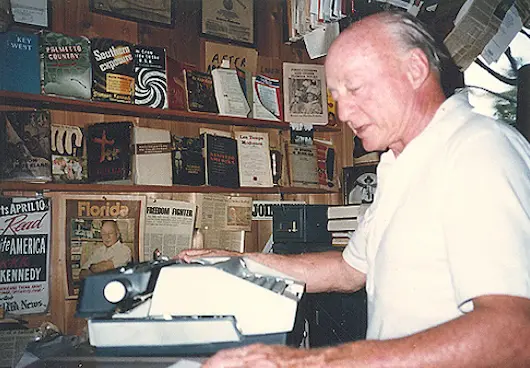

Stetson Kennedy in 1947. (AP Photo)

As he grew older, he continued to see the ways in which racism and discrimination had saturated all aspects of life in the South, including the growing influence of the Ku Klux Klan. As a student at Robert E. Lee High School, Kennedy began writing poems and stories based on the experiences of his Florida neighbors during Jim Crow. He went on to attend the University of Florida but left in 1937 at the age of 21 to take a position with President Franklin Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration, under its Florida Writers Project.

There, he oversaw the collection of folklore, oral history, and ethnic studies throughout the state, which was home to diverse multicultural communities, including Seminole Native Americans, Latinos, African Americans, whites, and numerous immigrant groups from around the world. Notably, he supervised and worked alongside renowned writer Zora Neale Hurston.

Ineligible for army enlistment due to a back injury, Stetson Kennedy published his first book, Palmetto Country, in 1942 based on the material he’d collected in his role with the WPA; it garnered widespread acclaim after its publication in the American Folklore Series. Soon thereafter, he began working as an editorial director for a political action committee in Atlanta, where he became fiercely devoted to the Civil Rights cause. Kennedy wrote stories about the ugly truths of Jim Crow, the racism that acted as the backbone of Southern politics (including interference with the voting rights of Black Americans), the Ku Klux Klan, and more.

- More stories: When Columbia University Expelled Robert Burke for Anti-Nazi Protests in 1936

- More stories: How Isaac Wright Jr Overturned Life Sentence & Became a Lawyer

- More stories: Reckless Eyeballing: How Matt Ingram’s Story Reveals Fear of Black Sexuality

“It’s my belief that writers, like ordinary people, serve one of two purposes in life: either social or anti-social. I cannot see how a writer can be neutral,” he once said.

A few years later, in 1945, Kennedy transitioned to working as a journalist for a New York-based leftist newspaper where his work often appeared in other publications, allowing him to build a reputation as one of the nation’s leading sources on the realities of the Jim Crow South.

Stetson Kennedy Infiltrates the Ku Klux Klan

It was at that newspaper that Stetson Kennedy began his work infiltrating the nefarious Ku Klux Klan. “All my classmates were overseas fighting Nazism,” Kennedy told NPR during an interview in 2005, “which is a form of racism…in our own backyard we had our own racist terrorists, the Ku Klux Klan. And it occurred to me that someone needed to do a number on them.”

Beginning in 1946, Kennedy infiltrated multiple Klans under an alternate identity by the name of John S. Perkins, working with the Georgia Bureau of Investigation and the Anti-Defamation League. Kennedy then shared KKK members’ names with journalists, fed information to law enforcement agencies to assist in prosecutions, and exposed Klan secrets via public radio broadcast.

30-year-old Stetson Kennedy leaves the U.S. Capitol building in Washington, D.C. on Sept. 10, 1947. He was escorted away by police from the Un-American Activities Committee Room. (AP Photo)

Throughout his years as a double agent, Kennedy partnered with two specific radio programs: the ultra-popular The Adventures of Superman and Drew Pearson’s Washington Merry-Go-Round. “Every Sunday we would broadcast the minutes of the Klan’s last meeting. And I would provide the names of all the policemen and deputies, the judges and prosecutors, and businessmen and officeholders who had attended the Klan meeting. And, of course, they never showed up again,” Kennedy later recounted.

In 1946, Stetson Kennedy published Southern Exposure, the first of his books to reveal in print the secrets of the Klan’s operations, among other tools employed in the South to uphold systems of discrimination.

The following year, Kennedy cleverly turned over to the IRS discarded paperwork from the Atlanta grand dragon’s trash, revealing that the Klan owed over half a million dollars in taxes from a 1944 assessment. This act compelled the state of Georgia to revoke the group’s corporate charter. Kennedy himself even contributed to the drafting of the brief which the state used in the case.

Later in 1947, Kennedy revealed his secret identity by testifying in court against two leaders of an Atlanta organization called the Columbians, a new-Nazi group which he’d also infiltrated. Largely because of Kennedy’s testimony, both men were convicted of inciting to riot and usurping police power, and the group dissolved.

- More stories: How a Retractable Syringe Exposed Powerful Group Purchasing Organizations

- More stories: Right-Wing Attacks on No-Fault Divorce Are a Dangerous Reality for Women

- More stories: Echoes of Slave Patrols in ICE Raids: What Abolitionists Can Teach Us

Life After the Klan

After Kennedy’s double life in the KKK was exposed, he was unable to continue his infiltration work. However, he soon found other ways to continue his activism. In 1950, he ran for the U.S. Senate as a write-in on a “Total Equality” ticket, but he finished in last place.

In 1951, he returned to court to testify against the Klan’s bombings of Black homes, Jewish synagogues, and Catholic churches. The following year, he ran for Florida governor, but, having made some serious enemies throughout his career, saw his property firebombed and fled for Europe. The Klan had put a price on his head, and Kennedy later referred to himself as having been “the most hated man in Florida.”

Kennedy sits in front of his typewriter in 1991. (Source)

While abroad, Kennedy published another book, I Rode with the Ku Klux Klan, where he detailed his cooperation with the FBI to disclose inside Klan information and blended his firsthand experiences infiltrating the KKK with similar accounts from another source. (Originally published in England in 1954, it was renamed and republished in the United States in 1990 under the title, The Klan Unmasked.)

While living in France, Kennedy wrote articles for publication in Les Temps modernes, a magazine founded by Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. Sartre also secured a publisher for Stetson Kennedy’s next book, Guide to Jim Crow. Published in 1959, this book examines America’s long history of racial discrimination laws.

- More stories: The Lives of Ferguson & Black Lives Matter Activists Cut Short

- More stories: Jennifer Schuett: A Survivor’s 19-Year Journey to Justice

- More stories: Book Banning in the U.S. at an All-Time High

Later Activism Work and Published Books

Stetson Kennedy returned to the States shortly before the turn of the decade and continued to fight fervently for racial equality in America. He participated in lunch counter sit-ins in downtown Jacksonville; reported on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s demonstrations in St. Augustine for the Pittsburgh Courier, the nation’s most prominent Black newspaper; and worked alongside fellow Civil Rights activist Alton Yates at the Greater Jacksonville Equal Employment Opportunity Commision and Youth Crisis Center. He continued to write for the Courier via his column “Up Front Down South,” and became assistant director for President Lyndon Johnson’s anti-poverty program in 1965.

Kennedy is interviewed at a Florida conservation event to protect the St. Johns River in 2009. (Source)

Kennedy went on to write several more books about both the intense racism of the American South and the rich folklore of his home state, including Southern Exposure: Making the South Safe for Democracy; After Appotmattox: How the South Won the War; Grits and Grunts: Folkloric Key West; and The Florida Slave.

In 2008, he released dozens of historical KKK documents online that he’d collected throughout his years of espionage, from the Klan’s constitution and by-laws to The Seven Symbols of the Klan and the Klansman’s Manual.

The Legacy of Stetson Kennedy in a Racially Divided America

Kennedy’s tireless work toward ending racial injustice in America has been recognized and honored widely throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. First in 1947, Kennedy was nominated for the Freedom House Freedom Award. Forty-five years later in 1992, he was granted both the NAACP Freedom Award by Florida’s Seminole County Branch and the Jules Verne Medal of Honor by the Intercontinental Conference on Civil Rights and the Force of Law, based in France.

In 2005, Kennedy was inducted into the Florida Artists Hall of Fame by the Florida Department of State. In 2010, he was named a “Citizen Above Self” Finalist by the Congressional Medal of Honor Society of the U.S. and granted the Dorothy Dodd Lifetime Achievement Award by the Florida Historical Society.

Kennedy’s ashes are interned on the Beluthahatchee Lake after his memorial service on October 1, 2011. (Source)

The Stetson Kennedy Foundation, begun by Kennedy himself and based in Fruit Cove, FL, remains “dedicated to human rights, social justice, environmental stewardship, and the preservation and growth of folk culture.” Kennedy’s life’s work – including the essays, letters, and articles now known as the Stetson Kennedy Papers – is now archived and viewable online via the P.K. Yonge Library of Florida History at the University of Florida.

Kennedy died in 2011 at the age of 94, but his legacy of courageous activism lives on. His advice for the next generation of racial justice activists? “Pick a cause and stick to it.”

0 Comments