How Cassie Chadwick Pulled Off One of the Greatest Bank Heists in History

Cassie Chadwick, born Elizabeth Bigley, was a prolific con artist who defrauded America’s wealthiest bankers at a time when women couldn’t even vote, granting her the title, “Queen of Ohio.” (Source)

August 17, 2025 ~ By Brooke Pland

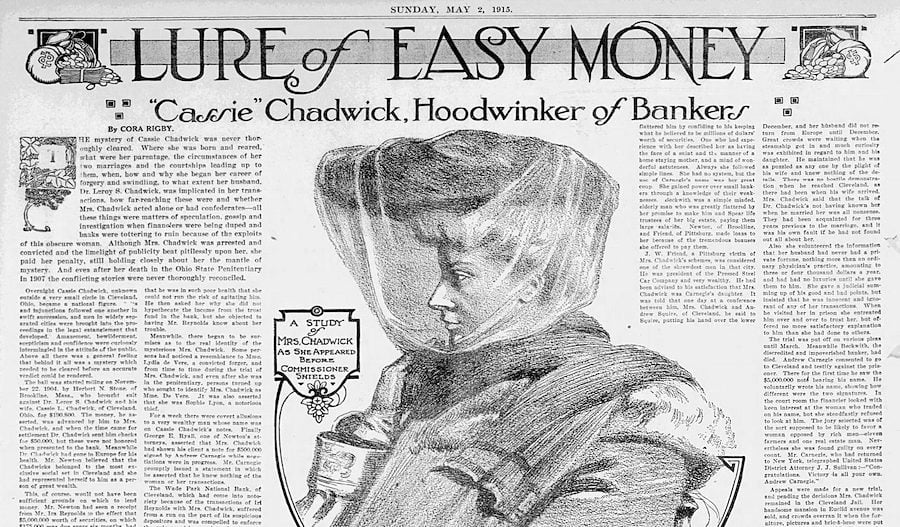

Female con artist Cassie Chadwick leveraged Gilded Age prejudices to scam her way into millions of dollars in what historians now call the “Carnegie Con”

In 1905, Cassie Chadwick was convicted of conspiracy against the U.S. government and conspiracy to defraud a national bank. She had conned banks, businessmen, and investors out of millions dollars – at least $35 million today – by claiming to be an heiress to Andrew Carnegie’s fortune. Living a lavish lifestyle on borrowed money and going undetected as a fraud for years, Chadwick earned herself the nickname, “The Queen of Ohio.” The conviction concluded her decades-long career as a solo female con artist who pulled off one of the greatest bank heists in history.

- Chadwick’s Roots as Elizabeth Bigley

- Bigley Cons Her Way Through Ohio & Pennsylvania

- Gilded Age Con Artist Becomes Cassie Chadwick

- The Carnegie Con Sweeps Cleveland

- Queen of Ohio Outed as a Con Artist

- Cassie Chadwick’s Legacy in the Victorian Era

Chadwick’s Roots as Elizabeth Bigley

Cassie Chadwick was born in Ontario, Canada in 1857 as Elizabeth Bigley. Her first major attempt at a con was at age 13. By writing a letter to herself announcing the death of a relative who’d left her a small inheritance, she deceived a local bank into issuing her checks connected to the relative’s nonexistent accounts. She was caught shortly thereafter and let off with a warning, but Bigley would soon try again.

In her early twenties, Bigley once more attempted her inheritance hoax, now with more careful attention to detail. She wrote herself a letter, this time from a fictional Ontario attorney, notifying her of $15,000 left to her by a wealthy philanthropist; she then obtained business cards reading, “Miss Bigley, Heiress to $15,000,” which mimicked the calling cards of the Victorian social elite.

Example of the $15,000 notes that Bigley made fraudulent purchases with. Taken from The Brantford Weekly Expositor, Jan 31, 1890. (Source)

Using the cards as proof of her fabricated economic position, Elizabeth Bigley purchased goods from high-end shops with checks written for more than the total cost of the items, and the merchants gave her the difference in cash – a common 19th-century business practice. Pocketing the cash, Bigley would leave the stores with both real money and real goods, having begun with neither. The scheme continued for months; eventually, Bigley was arrested for forgery but evaded conviction on grounds of insanity.

- More stories: How Stetson Kennedy Infiltrated the KKK & Changed the Jim Crow South

- More stories: How the Hatpin Panic Changed 20th Century Gender Politics

- More stories: Secessions of the Plebeians: A General Strike in Ancient Rome

Bigley Cons Her Way Through Ohio & Pennsylvania

Elizabeth Bigley soon left Ontario for Cleveland, Ohio alongside her newlywed sister. While living with the couple, Bigley attempted to take out a loan using the equity of their home furnishings as collateral. Her sister’s husband kicked her out after discovering her scheme and she moved across town, where she met her first husband, Dr. Wallace S. Springsteen.

They married in December of 1883, but after a local newspaper published the marriage announcement, angry merchants began showing up at their house demanding repayment for the money Bigley had swindled them out of in her continual shopping scams. Dr. Springsteen settled Bigley’s debts but called off the marriage after a mere 12 days.

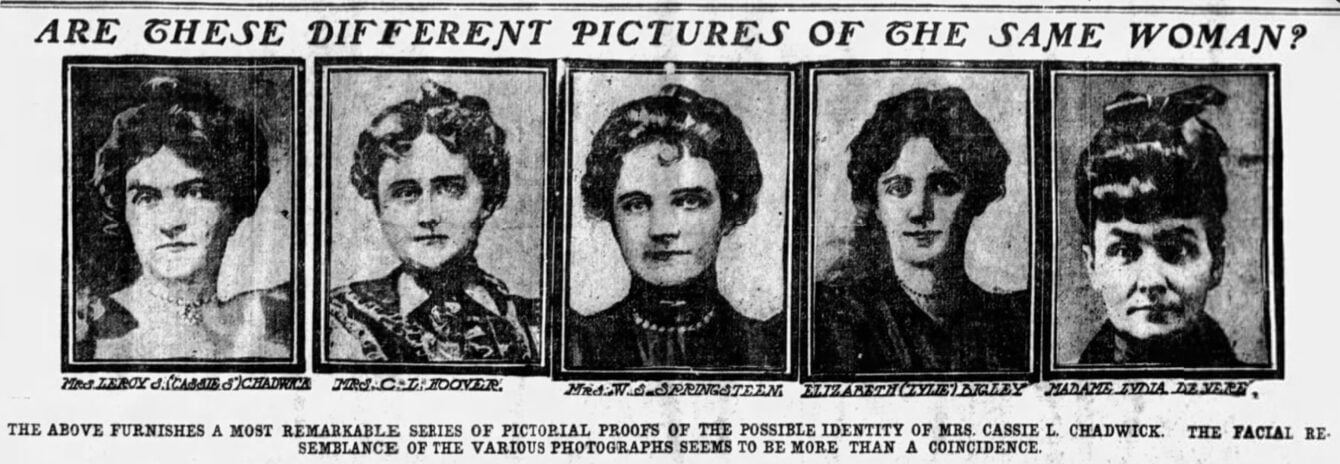

Making her way to Erie, Pennsylvania and taking the name Madame Marie LaRosa, Bigley then began working as a fortuneteller. She entered into a brief marriage with a local farmer and then a second with local businessman C.L. Hoover. After Hoover’s death in 1888, Elizabeth Bigley moved to Toledo, changed her name to Madame Lydia DeVere, and reestablished her fortunetelling con.

The Cleveland Leader features one of Bigley’s identities, Madame Lydia DeVere. (Source)

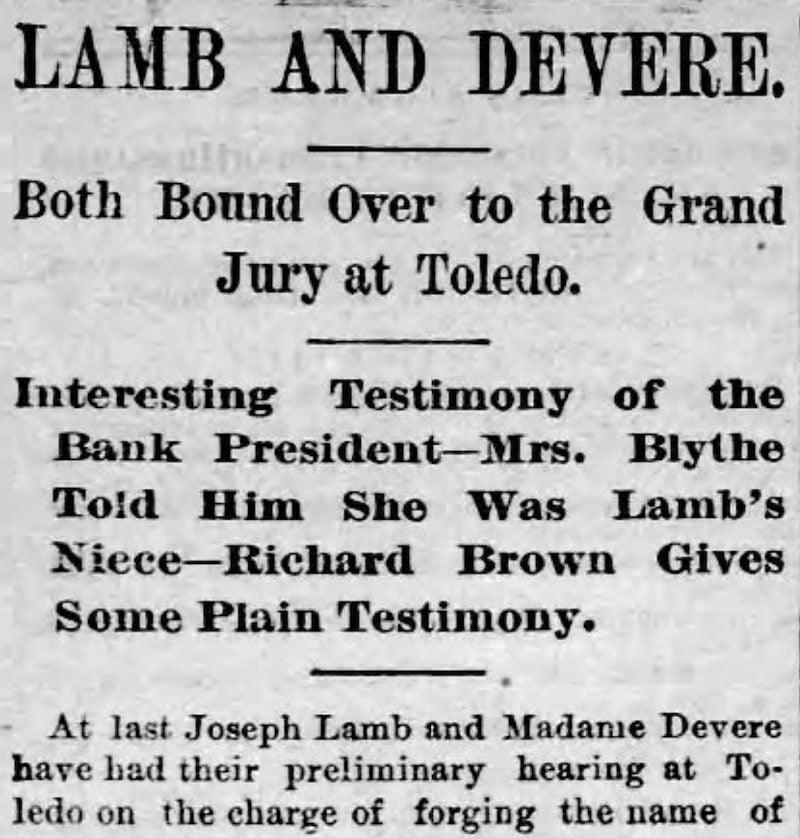

Bigley enlisted one such client, Toledo businessman Joseph Lamb, to cash fraudulent checks at local banks under the impression that they were legitimate, obtaining roughly $40,000 before the banks discovered her scheme. She was arrested and sentenced to 9.5 years in state penitentiary; however, after three years of writing letters of supposed remorse to the parole board, then-Governor William McKinley released her early.

Local coverage of the fraudulent check scam orchestrated through the Madame Lydia Devere identity. Taken from The Evening Post in Toledo, January 25, 1890. (Source)

Elizabeth Bigley Becomes Cassie Chadwick

Out of jail, Bigley headed back to Cleveland under the name Cassie L. Hoover. In 1897, she married a fourth time to Dr. Leroy S. Chadwick, a wealthy physician and widower from one of the city’s oldest families. Now living as Cassie Chadwick amongst Cleveland’s high society, she began spending extravagantly on her husband’s dime; newspapers later reported her most noteworthy expenditures, including entire trays of gems and eight grand pianos as gifts for friends.

Her husband soon objected to her spending, so this wildly successful female con artist decided to obtain further funding for herself. She reestablished her decades-old inheritance con, this time claiming connection to business tycoon Andrew Carnegie. That same year, she planned a visit to Carnegie’s Fifth Avenue mansion in New York City, accompanied by a Cleveland acquaintance.

The Dayton Daily News examines Bigley’s many identities, including Cassie Chadwick, C.L Hoover and Madame Lydia Devere. Appeared in print on December 10, 1904. (Source)

After telling her companion she had business to conduct at “her father’s house,” Chadwick briefly entered the residence (by pretending to inquire after the staff) and returned with millions of dollars’ worth of forged promissory notes and Carnegie securities. She explained that she was Carnegie’s illegitimate daughter and swore the gentleman to secrecy, knowing he would not be able to keep the information to himself. Upon their return to Ohio, the news of Cassie Chadwick’s latest con spread rapidly.

- More stories: When Columbia University Expelled Robert Burke for Anti-Nazi Protests in 1936

- More stories: Right-Wing Attacks on No-Fault Divorce – A Dangerous Reality for Women

- More stories: What Daughters of Bilitis Achieved for Lesbian Rights in the U.S.

The Carnegie Con Sweeps Cleveland

Back in Cleveland, Chadwick began taking out large loans from dozens of banks based on the forged Carnegie documents, building a complex system in which she’d pay off each loan with the money from another, all the while financing her exorbitantly expensive lifestyle. The “Carnegie Con” continued for the better part of a decade, allowing Chadwick to amass several million dollars in debts from banks and the wealthy businessmen running them to make her scheme one of the greatest bank heists in history.

Soon, Cassie Chadwick got involved with Citizen’s National Bank of Oberlin, Ohio and its president, Charles Beckwith, persuading him to loan her $800,000 – three times the bank’s reserve sum – and additional $100,000 of his own money. Chadwick even went so far as to sign bank notes in Beckwith’s name. The con would eventually force the bank to shut its doors, having lost its entire reserve after loaning Chadwick all its patrons’ savings.

Charles Beckwith, president of Citizen’s National Bank, dies after Chadwick’s con shuttered his bank. (Source)

Among the other wealthy businessmen Chadwick built relationships with was Herbert B. Newton, an investment banker who loaned her $104,000 of both his business and personal money after she promised him a massive return on investment at $190,800. However, after Chadwick never paid back the money, Newton took her to court in November of 1904.

The Queen of Ohio Outed as a Con Artist

As news of the trial spread, people began connecting Cassie Chadwick with her former persona, Lydia DeVere. Sources came forward to assert that they were, in fact, the same person, and that DeVere had scammed countless people years prior. The trial quickly became a national sensation, with many believing this female con artist to be innocent.

“In the history of ‘frenzied finance’ in this country,” wrote the Clinton Republican in December 1904, “and in the entire world for that matter, no case the equal of that of Mrs. Chadwick has ever been known…How this woman, apparently alone, outwitted shrewd bankers and hard-headed business men and borrowed fortunes on mythical securities and bogus notes seems almost beyond comprehension, but it seems only too true.”

- More stories: Masako Katsura: Japanese Billiards Player Who Broke Gender Barrier

- More stories: How a Retractable Syringe Exposed Powerful Group Purchasing Organizations

- More stories: The Fate of Margaret Morgan in Prigg v. Pennsylvania

The news even reached Andrew Carnegie himself, and he traveled to Cleveland to attend the trial. The New York Times reported that upon inspecting the fraudulent documents Chadwick had created, Carnegie laughed at the spelling and punctuation errors no one ever caught and was shocked at the “gullibility of her victims.”

Chadwick is found guilty on all seven charges, including attempting to defraud the United States, on March 10, 1905. (Source)

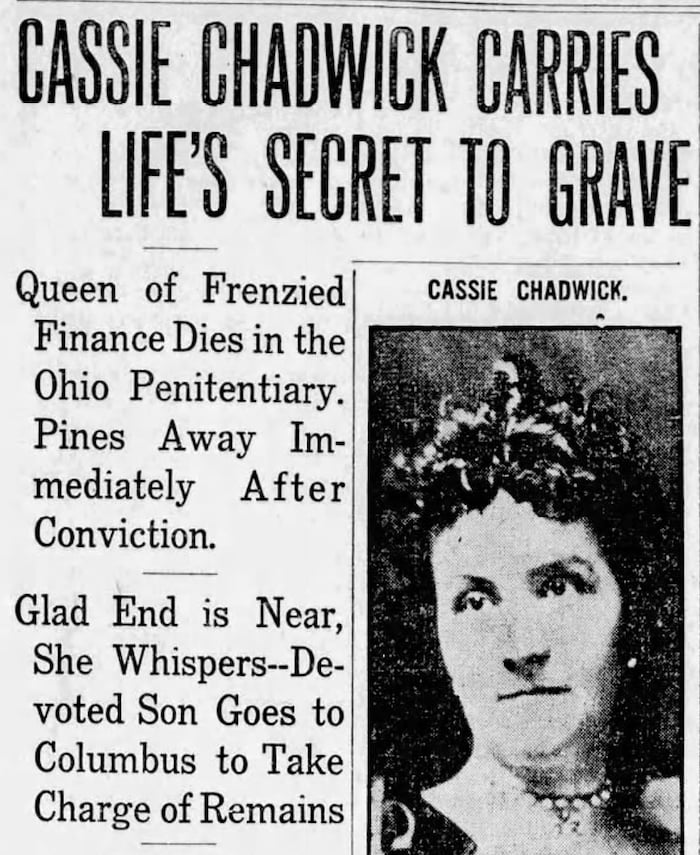

In court, Chadwick denied all charges brought against her, including that she claimed to be connected to Carnegie. On March 10, 1905, Cassie Chadwick was convicted on 7 counts of conspiracy against the government and conspiracy to con Citizen’s National Bank of Oberlin, fined $70,000, and sentenced to 14 years in prison. One local paper reported the conviction to be “a sensational conclusion to a trial that has been replete with absorbing interest.”

In prison, Chadwick suffered from “total nervous collapse,” and she died less than three years into her sentence in October of 1907.

A Female Con Artist in the Victorian Era

At a time when women had few financial rights in America, just how did Cassie Chadwick become “the greatest grifter of the Gilded Age”? Women weren’t legally allowed to obtain bank loans without a male co-signer until 1974, yet Chadwick became “the singular woman whose vast swindling operations… attracted the attention of the entire world.”

Historian Annie Reed, author of The Imposter Heiress, argues that Chadwick “used sexism as a weapon.” By accepting massive interest rates and even offering huge bonuses upon the return of the loans, Chadwick convinced her exclusively male lenders that she was a naive, silly woman who didn’t understand how finance worked.

Cassie Chadwick / Elizabeth Bigley died in prison on October 10, 1907. (Source)

Eager to exploit her, these businessmen thought they landed the deal of a lifetime and never considered that Chadwick might be clever enough to prey upon their false assumptions. They rarely investigated the forged documents and were never suspicious of the lack of collateral she could provide for these loans, simply because they never suspected that a woman could be smart enough to deceive them. It wasn’t until Chadwick’s trial that the role gender had played in her plans became more apparent.

- More stories: The Mayhem of Hell-Cat Maggie In New York City

- More stories: Jovita Idár’s Fight for Mexican-American Rights in Texas

- More stories: Yuri Kochiyama At The Intersection of Black Power & Asian Movements

Moreover, Cassie Chadwick was observant: She emulated the rich who threw money around casually and without concern. Her confidence and charisma ensured that she was taken seriously and never questioned – characteristics reminiscent of modern female con artists like Anna Sorokin.

“[Throughout] the erratic and varied criminal career of Mrs. Cassie L. Chadwick, whose persuasive eloquence caused some of the shrewdest financiers of the country to part with their money,” wrote The Fort Worth Telegram in 1908, “there was never a hint that she was a smuggler.” These traits likewise earned Chadwick her most famous nickname, “the Queen of Ohio.”

Furthermore, Chadwick was strategic in selecting Carnegie as her fictional connection. By 1901, Carnegie was the richest man in the world and widely known; borrowing even large sums of money in his name would seem unimportant for someone of his wealth. Besides, anyone seeking to check the validity of Chadwick’s claims would have no guaranteed way of contacting Carnegie. Chadwick also made the promissory notes explainable by claiming she was not a legitimate child of Carnegie but an illegitimate one whom Carnegie was paying to keep quiet about the scandal.

Because of Cassie Chadwick’s cleverness in plan, conduct, and follow-through, some historians speculate that she conned her way to even more money than reported, as other men she conned might have been reluctant to come forward.

While the exact monetary value of her scheme may never be truly known, the Queen of Ohio surely managed one of the greatest bank heists in history – single-handledly, and amidst a financial system which had deemed her helpless, no less. This “mysterious woman whose audacity [staggered] the whole financial world” has since been described as superior to Charles Ponzi and named one of TIME Magazine’s Top 10 Imposters of all time.

- More stories: The Triumphs of Edward Gardner at the 1928 Bunion Derby

- More stories: Gallus Mag, The Most Brutal Bouncer in 1860s New York

- More stories: Alvin “Shipwreck” Kelly: Flagpole Sitting Of The 1920s

0 Comments