When Columbia University Expelled Robert Burke for Anti-Nazi Protests in 1936

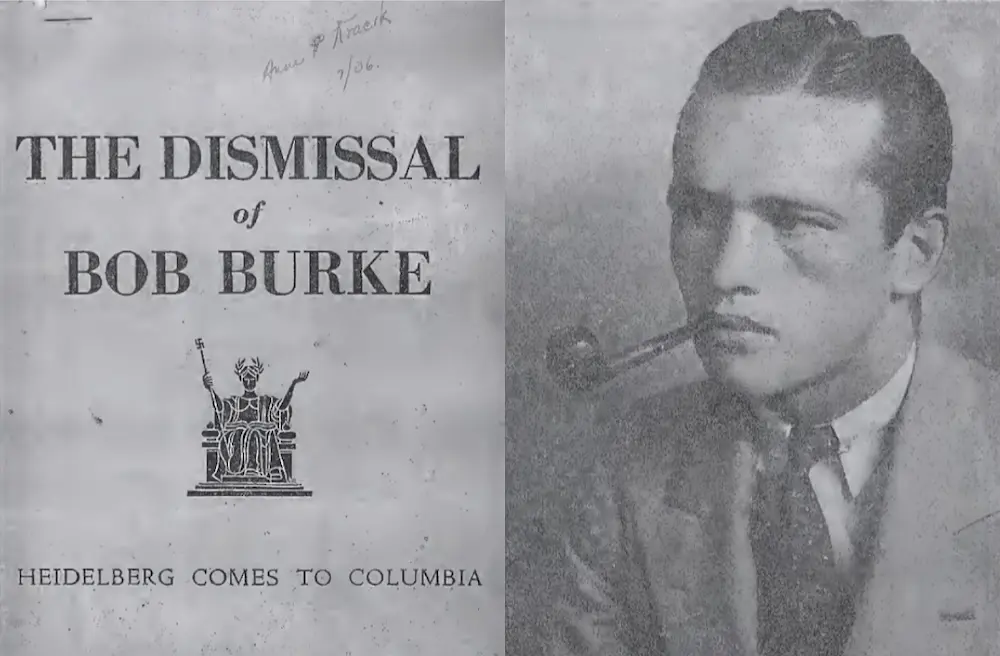

“The Dismissal of Bob Burke. Heidelberg Comes to Columbia” is a 20-page document from the ACLU and other organizations that details the events at Columbia University that led up to Burke’s expulsion and its aftermath in 1936. (Source)

March 15, 2025 ~ By Shari Rose

Soon after Robert Burke led an anti-Nazi protest at Columbia in 1936, he was expelled. In 2025, history repeats itself over and over.

Robert Burke was a junior at Columbia University who dared to protest the administration’s ties to Nazi Germany in 1936. Organizing a group of 300 students, he led a demonstration in front of President Nicholas Butler’s home to oppose the university’s support of an event that propagated Nazi policies and beliefs on college campuses. What transpired after that evening is a pattern of severe punishment and silencing of dissent levied against nonviolent student protesters who demonstrate against genocidal regimes. And it’s happening again at Columbia and across universities in the U.S. today.

- Columbia Accepts Invitation to Heidelberg University

- Robert Burke Leads Anti-Nazi Protest at President’s House

- Administration Targets Burke for Leading Anti-Fascist Demonstration

- Burke Fights for Reinstatement to Columbia University

- Columbia’s Expelling of Nonviolent Student Protesters Against Genocide Are Back

- Trump Administration’s Takeover of Universities Follows a Similar Pattern

The Rise of Nazism on University Campuses in 1930s

Soon after Adolf Hitler rose to power, Germany’s Civil Service Law was enacted in April 1933. Its goal was to remove civil servants of Jewish descent or non-Aryan backgrounds from their roles as teachers, professors and government employees. Famously, Albert Einstein left Nazi Germany in 1933 as a direct consequence of this legislation.

The law also sought to fire or remove any individual who refused to abide by Nazi beliefs, and the party took a special interest in German universities. One such institution, Heidelberg University, supported the Nazi regime and proactively removed scores of professors and students for racial and political reasons. Just one month after the Civil Service Law went into effect, university faculty and students took part in book burnings on Heidelberg’s campus.

A photograph of Heidelberg University’s campus taken on June 11, 1931. (AP Photo)

In February 1936, Heidelberg University invited representatives from universities in the U.S. and Europe to attend a 550th anniversary celebration of its founding. While Oxford, Cambridge and others rejected the invitation and hoped their absence would serve as a “condemnation of Nazi attacks upon academic freedom,” Columbia University agreed to attend, setting the stage for anti-fascist protests on its campus.

Columbia Accepts Invitation to Heidelberg University

Columbia Assistant Secretary Philip Hayden announced on February 28, 1936 that the administration would send a representative to Heidelberg because “it is the custom of Columbia University to be represented, whenever conveniently possible, at all celebrations of educational institutions here and abroad.”

Writer’s note: Made in collaboration with the American Civil Liberties Union, the American Student Union chapter at Columbia and the Burke Defense Committee, a 20-page document called “The Dismissal of Bob Burke. Heidelberg Comes to Columbia” details the timeline of events leading to Burke’s expulsion and after. Much of the information from February 1936 to July 1936 in this article comes from that document.

Many students were furious at the administration’s decision to support an event that propagated Nazi beliefs and policies in higher education. The university’s student newspaper, the Columbia Daily Spectator, responded on March 2 by calling for Columbia to rescind its acceptance. Student journalists argued that the university’s presence “will in effect be bestowing a benediction upon the spoliation of education and culture by the Hitler regime.”

They continued: “[Columbia] will be giving its approval to those who have suppressed academic freedom, perverted the content and teaching of all branches of learning, fostered a fraudulent ‘race science,’ dismissed and persecuted scholars on religious, political and racial grounds.”

Soon after Hayden’s announcement, the American Student Union (ASU) chapter voted to oppose the university’s participation and organized demonstrations against it. They created a petition and garnered more than 1,000 signatures from students and faculty, including Nobel Prize winner Harold Urey.

Dr. Nicholas Murray Butler, left, president of Columbia University, presenting the civil forum medal of honor to Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd in New York on October 31, 1930. (AP Photo/Anthony Camerano)

On March 30, Columbia President Nicholas Murray Butler agreed to meet with a committee of students regarding the Heidelberg event. During that meeting, he promised to provide “full consideration to the views of the students in a study of the entire matter.” But Dr. Butler never spoke with them again.

So, Columbia students made their divestment demands known through a nonviolent protest at his home.

Robert Burke Leads Anti-Nazi Protest at Columbia President’s House

Before Robert Burke was expelled from Columbia University, he was the president-elect of his junior class and a leading member of the America Student Union at the university. A native of Youngstown, OH, he was disgusted by Columbia’s decision to join Heidelberg’s anniversary celebration as well as the administration’s refusal to meet with protesting students.

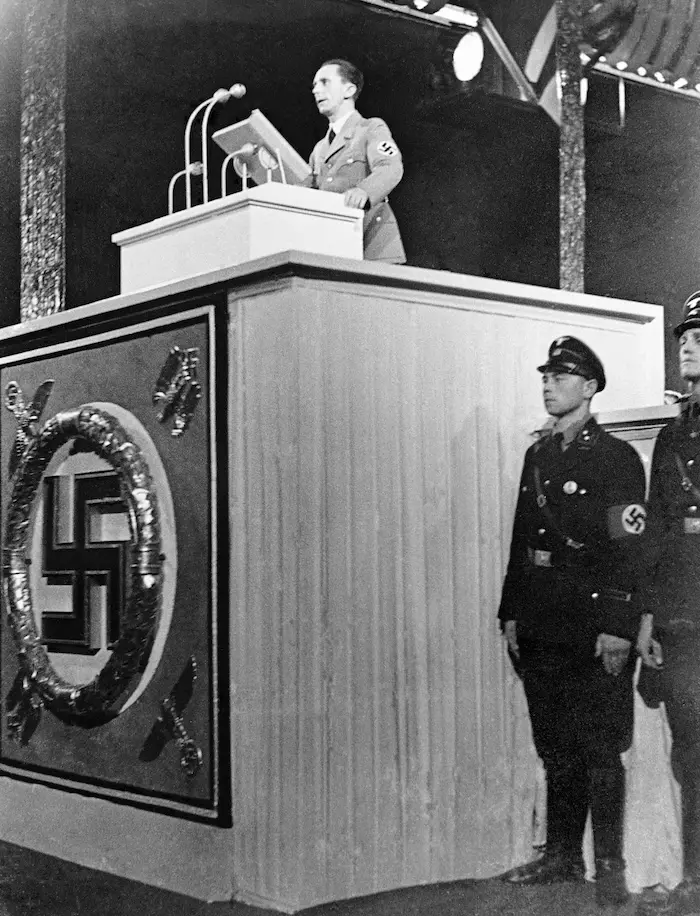

It should be noted that The New York Times reported on April 28 that Joseph Goebbels himself would be in attendance at the event. The article reads: “Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels and other Nazi functionaries will be among the most prominent hosts to scholars and scientists who have been invited to represent the universities of the world.”

Germany’s Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels denounces Jewish Bolshevism in a speech delivered at the Nazi Party Congress on September 10, 1936. (AP Photo)

In other words, it had become clear to students that this engagement with Heidelberg University was not simply an academic courtesy, but rather a tacit endorsement of the Nazi takeover of universities and colleges.

Nearly 45 days after President Butler promised to meet with students and reconsider the invitation, Philip Hayden told the student committee that “Dr. Butler has nothing to see the committee about.”

In response to the administration’s stonewalling, Robert Burke led a group of 300 students onto South Field on the evening of May 12, 1936. After engaging in a mock book burning to criticize Columbia’s ties to Nazi Germany, student protesters went to Dr. Butler’s home “in a final attempt to shake his indifference to university opinion.”

Toward the end of the 30-minute demonstration, Burke gave a speech. According to affidavits signed by Columbia students who were there, Burke said in part: “Nicky, and I hope you hear this too, you can send a representative to Heidelberg but let it be known that he is not the choice of the student body.”

- More stories: Right-Wing Attacks on No-Fault Divorce Are a Dangerous Reality for Women

- More stories: Israel Killed Record-Breaking Numbers of Journalists & Aid Workers in Just 6 Months

- More stories: Echoes of Slave Patrols in ICE Raids: What Abolitionists Can Teach Us

The protest was then peacefully disbanded and demonstrators went home. Student affidavits contend that “not only did Burke refrain from any personal or abusive language but that he also attempted to quiet a few individuals who shouted personal comments.”

But nine days after the anti-Nazi demonstration, Robert Burke was summoned to Dean Herbert Hawkes’ office.

University Administration Targets Burke for Leading Anti-Fascist Protest

On May 21, Burke met with Dean Hawkes and summarized their meeting as follows:

“[Hawkes] confronted me with the accusation of having been a leader of a demonstration which was in exceedingly poor taste, rowdy and had violated the sanctity of Dr. Butler’s home. He told me that someone had shouted profane remarks about Dr. Butler and that someone had left picket signs in the foyer of Dr. Butler’s house. I told the Dean that I hadn’t heard the profanity and that I was sorry that someone had left picket signs … I maintained that as far as picketing Dr. Butler’s house went and speaking in front of it, we were within our rights and well within the bounds of decency. This became our major point of difference.”

Burke said he warned Dean Hawkes that his expulsion would have a chilling effect on student speech at Columbia: “I told the Dean that if I were expelled it would appear to the student body that this action was an attempt to frighten the ASU out of any action of significance and to frighten politically conscious students so that they would not take part in ASU affairs.”

Three days later, the American Student Union sent a letter to Dean Hawkes to apologize for any obscene language that may have been used during the demonstration outside Dr. Butler’s house.

One week after their initial meeting, Dean Hawkes again confronted Robert Burke and accused him of “distorting” what he said during their previous meeting. Burke recounted that the two of them “again argued the right of students to picket Dr. Butler’s house and I again apologized for the two questionable matters, making it clear that I had not used profanity nor left the picket signs.”

In a short letter sent from Dean Hawkes himself, Robert Burke was expelled from Columbia University on June 16, 1936.

Burke Fights for Reinstatement to Columbia University

In “The Dismissal of Bob Burke,” collaborators with the ASU, ACLU and Burke Defense Committee come to the conclusion that the student’s removal is “clearly an attack on the right of student organization and action.”

The piece continues: “Burke’s expulsion is an attempt to stifle student opinion. It is a challenge to every advocate of democratic education. It is a shocking forerunner of that kind of arbitrary, ruthless academic dictatorship to which education has been subjected in Germany. Columbia sent a representative to Heidelberg; are Heidelberg methods coming to Columbia?”

In the months after his expulsion, Burke worked to be reinstated as a student. In a July 10 letter to Dean Hawkes, he made his case:

“I have, sir, worked hard and earnestly for the past several years to gain an education. I entered Columbia because of its reputation for liberal and progressive action. During the two years I have been in attendance there I have come to respect many of my professors and the learning inherent in the institution. Certain other aspects I have come to abhor. This is, I believe, a natural reaction. Those aspects I disliked I protested against in the hope that some change might be accomplished. This, to me, was loyalty to Columbia,” Burke wrote.

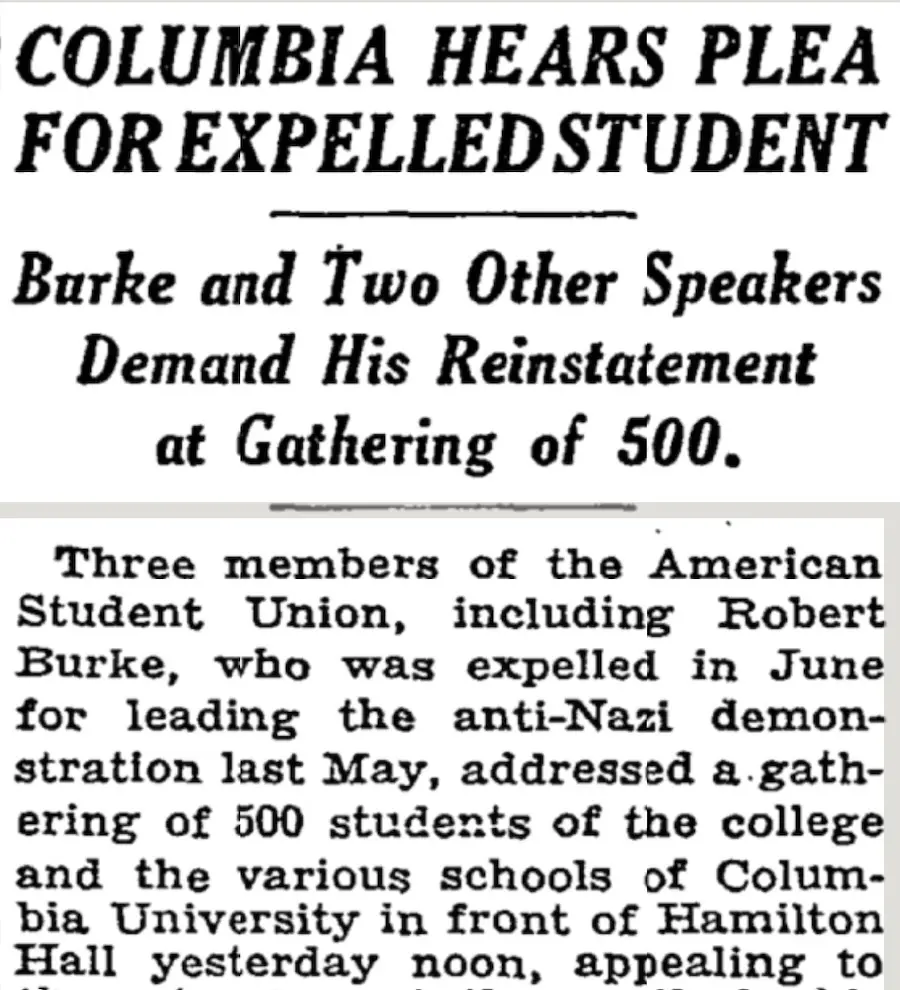

The New York Times covers Burke’s short return to Columbia University in September 1936. (Source)

On September 24, Robert Burke and two other members of the ASU went back to Columbia’s campus. Standing in front of Hamilton Hall, he addressed a group of 500 students and asked them to support his reinstatement. Burke concluded that “It is a question whether the president, dean and trustees of Columbia will tell me what to think and do or whether I shall do what I think is right.”

Though Dean Hawkes refused to reconsider the expulsion, students at Columbia University kept fighting.

- More stories: Secessions of the Plebeians: A General Strike in Ancient Rome

- More stories: How Stetson Kennedy Infiltrated the KKK & Changed the Jim Crow South

- More stories: The Lives of Ferguson & Black Lives Matter Activists Cut Short

Columbia Students Protest Burke’s Expulsion

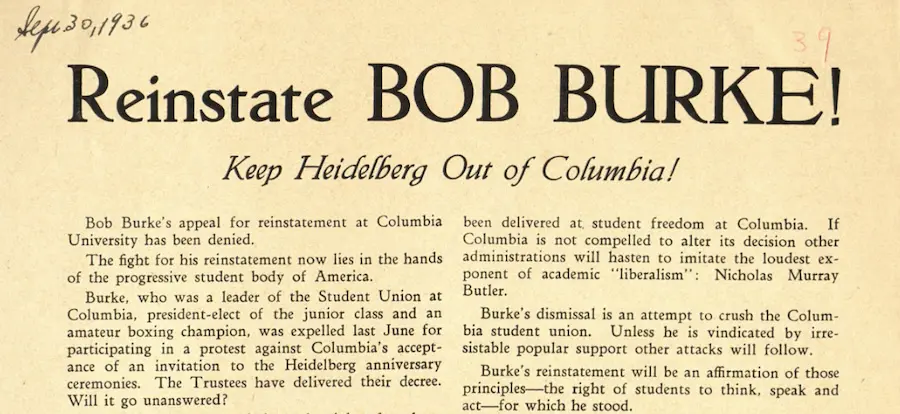

A student pamphlet titled “Reinstate Bob Burke! Keep Heidelberg Out of Columbia!” was widely shared on September 30. Among other statements, it contends that “Colombia’s refusal to reconsider this case has established the fundamental principle of the fight. If Burke’s expulsion is not rescinded a smashing blow will have been delivered at student freedom at Columbia.”

A protest pamphlet shared by the American Student Union demands Burke’s reinstatement at Columbia University and asks students to join a rally that evening. (Source)

Another pamphlet from the same day, titled “Burke Banned!” argues that the only reason Robert Burke was expelled from campus was because he had the courage to speak out against Nazism: “Burke was banned because he has the nerve to speak out against fascism in no uncertain terms.”

It continues: “Our administration sees fit to follow the decisions of Columbia and to itself sanction suppression of speed and thought. Our fight to maintain these rights is no new struggle here. We know what it means to be deprived of them.”

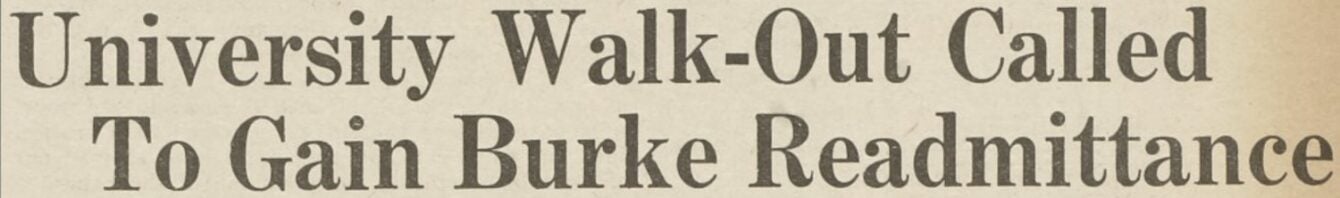

Student protesters call for a university-wide walkout to try to force the university administration to finally meet with the American Student Union regarding Burke’s expulsion. (Source)

On October 15, 1936, the Burke Defense Committee and the Columbia Chapter of the American Student Union called for a university-wide walkout to protest the administration’s stifling of anti-Nazi speech and its failure to address students’ concerns. Chairman of the Strike Committee, a student named Paul Thomson, explained why a walkout was necessary:

“The campaign has taken the form of petitions, leaflets, picket lines, mass meetings, legal action, and efforts to interview Dr. Butler. Through every possible agency it has been made clear the administration by the expulsion of Burke has challenged not only his fitness as a member of Columbia College, but also the very fundamental right of students to organize and demonstrate,” Thomson said.

By 1937, Robert Burke had returned to his hometown of Youngstown. He became a local organizer with the Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO) and was the chief organizer of a steel workers’ strike at Republic Steel. In June 1937, Burke was arrested during one of the demonstrations. On September 30, 1937, he was found guilty of rioting.

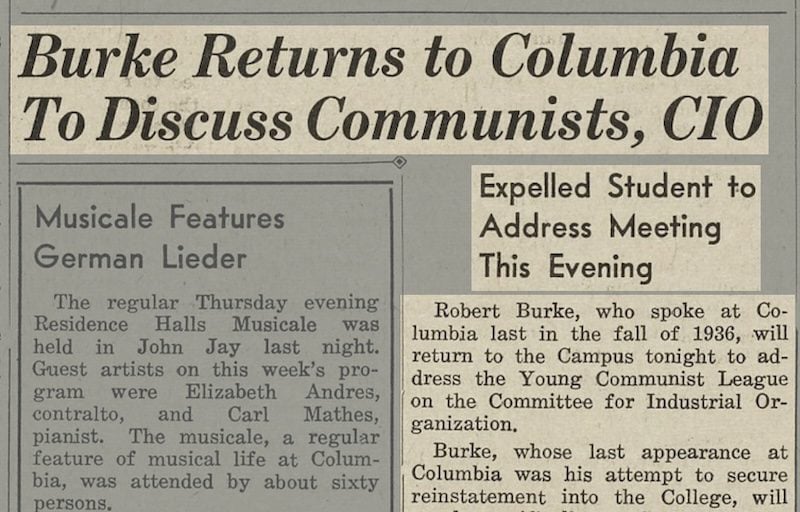

The following month, Burke dropped a lawsuit against Columbia University for his reinstatement. But he did return to campus on February 18, 1938 to address the Young Communist League and support the CIO’s efforts regarding workers’ rights.

In this article from the Columbia Daily Spectator, Burke returns to Columbia University in February 1938 to speak with the Young Communist League about CIO’s efforts in improving worker’s rights. (Source)

Columbia’s Expelling of Nonviolent Student Protesters Against Genocide Are Back

Nearly 90 years after Robert Burke’s expulsion, Columbia University is once again expelling student protesters who demand they cut ties with genocidal regimes. On February 21, 2025, Barnard College of Columbia expelled two pro-Palestinian students for “disrupting the first session of the History of Modern Israel course,” taught by a former IDF soldier.

One week later, Columbia expelled another student for taking part in the Hamilton Hall (known as Hind’s Hall to protesters) occupation in April 2024. Then on March 13, Columbia’s University Judicial Board announced that 22 students involved in last year’s building takeover would be punished with expulsions, suspensions or degree revocations. The administration also expelled Grant Miner, president of the Student Workers of Columbia-United Auto Workers,

For those who may not remember, Columbia students who opposed Israel’s genocide of Palestinians demanded that the university divest from Israel by engaging in large-scale encampment protests throughout 2024.

- More stories: The Riot Dogs Who Joined Protesters Against Police

- More stories: Crystal LaBeija: Iconic Drag Queen Who Transformed Queer Culture

- More stories: How School Portables Became Permanent Classrooms

The group largely leading the charge on campus, Columbia University Apartheid Divest (CUAD), is a coalition of student organizations dedicated to the anti-war movement and divestment from apartheid nations. Last April, nonviolent student protesters took over Hamilton Hall, renamed it Hind’s Hall in honor of six-year-old Hind Rajab who was killed by Israeli soldiers, and demanded that Columbia divest from Israel.

In response, Columbia President Minouche Shafik asked the NYPD forcibly remove students. Dressed in riot gear and wearing tactical equipment, hundreds of NYPD officers stormed the building, arrested nearly 300 people and cleared two encampments on the lawn. One officer fired his gun inside Hind’s Hall, but no one was hit.

As The Nation points out, Columbia students have engaged in multi-building takeovers and sit-ins in 1972, 1985, 1987, 1996 and 2016 to protest the university’s ties with South African apartheid, controversial U.S. foreign policies and more. None of those students faced the severity of punishments that pro-Palestinian students are facing today.

It’s also important to note that there were two Israeli students who sprayed a chemical agent on participants of a Gaza solidarity rally in January 2024. Several people were hospitalized from the attack. What was Columbia’s punishment for these two individuals who used violence against fellow students? Both received just 18-month suspensions and one was even rewarded $395,000 from the university in a settlement.

Why does it seem that Columbia’s harshest punishments are only reserved for students who protest against genocide and fascism? Perhaps that now brings us to Mahmoud Khalil, one of the protest movement’s most visible figures.

Trump Administration’s Takeover of Universities Follows a Similar Pattern

A recent graduate from Columbia’s School of International Public Affairs, Khalil is a 30-year-old Algerian citizen with Palestinian descent who organized many of the campus encampment protests. He is a green-card holder with permanent legal status in the U.S., but he was arrested by ICE inside university housing on March 8, 2025.

One week later, Mahmoud Khalil still has not been charged with a crime. Without any evidence to show, the Trump administration has argued that his presence in the U.S. could have “potentially serious adverse foreign policy consequences for the United States.”

What the Trump administration is doing now is a test-run for widespread arrests, detainments and deportations for students who oppose Israel’s genocide and America’s role in it.

Columbia’s third expulsion came on the same day that the Department of Justice announced the Federal Task Force to Combat Antisemitism would be visiting 10 university campuses, including Columbia. The Trump administration is making the horrifying argument that to oppose Israel’s genocide of Palestinians is in and of itself, antisemitic. In other words, Trump and his loyalists are making it illegal to protest genocide.

With the power of the presidency and Congress, this administration is destroying the very foundation of free speech and the right to protest in front of our eyes. And it will not stop at college campuses. This is only the second month of Trump’s rise to power. It’s the universities now, but it will expand everywhere else. If that sounds familiar, it’s because we’ve seen it happen before.

I hope we have the courage that Robert Burke and his peers did then, because it’s the same courage that pro-Palestinian students have across U.S. university campuses today, and it’s the kind of courage we all need in 2025 and beyond.

- More stories: Zazu Nova’s Legacy at Stonewall Deserves Recognition

- More stories: When Martha Mitchell Was Right About Watergate

- More stories: How Matt Ingram’s Story of Reckless Eyeballing Reveals Fear of Black Sexuality

- More stories: Wheelchairs & Airlines: Why Is Flying So Risky for Those With Disabilities?

0 Comments