The Triumphs of Edward Gardner at the 1928 Bunion Derby

Edward “Sheik” Gardner speaks in an interview ahead of the Trans-Continental Footrace, or Bunion Derby as it came to be called, on March 4, 1928. (Source)

February 22, 2021 ~ By Shari Rose

Updated January 27, 2024

At the 1928 Bunion Derby, runner Edward “Sheik” Gardner became a symbol of hope to millions of Black Americans

The 1928 Trans-Continental Footrace, or Bunion Derby as it came to be known, was a 3,422-mile-long ultramarathon that spanned from Los Angeles to New York City. An endurance runner named Edward Gardner traveled from Seattle to compete in the race, unaware of what his participation would mean to millions of Black Americans. This is the incredible true story of Edward Gardner and the Bunion Derby.

Edward Gardner’s Early Running Career

Edward Gardner was born in Birmingham, AL in 1898. After moving around for a while, his family settled down in Seattle, WA, where Gardner remained for most of his life. He loved to run as a child and excelled on his high school track team. As a teenager, he studied at Tuskegee University and continued to train as a long-distance runner, adding more miles to his runs and finishing them faster.

In 1915, Gardner set the Tuskegee school’s 5-mile record at 17 years old. Two years later, he won first place at Alabama’s Black state cross-country championship.

After graduation, Gardner moved back to Seattle in 1921 and became a steam boiler repairman. But he never stopped running. The following year, he competed in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer Washington State 10 Mile Championship. Over the years, he won the race three times. For his third win, Gardner beat the state record by five seconds.

Gardner slowly became a rising star in town, and newspapers like the Seattle Post-Intelligencer lauded him in the local press. The paper did not refer to his race in headlines and instead praised him for his athletic achievements, which was an unusual practice for newspapers at the time.

During the early 20th century, the mainstream, or white, newspapers rarely covered African American athletes. And when they did, media coverage used heavy racial overtones, referring to Black athletes as “Negroes,” and often omitting their names altogether.

But the Seattle newspapers were different. By and large, they treated Gardner with respect and rooted for his success as a hometown hero. With the increase in coverage, Edward Gardner began to amass a small fanbase. And his fans noticed his signature look on runs: a white tank top, white shorts, and a white towel wrapped around his head.

Seattleites thought Gardner looked like the star of the 1921 film, The Sheik, played by Rudolph Valentino. They shouted “Oh, you sheik!” or “Here comes the sheik!” and solidified Gardner’s nickname for the rest of his running career.

Gardner Signs Up for the Bunion Derby in 1928

In 1928, a wealthy sports agent named Charles C. Pyle sponsored the first annual Trans-Continental Footrace, a coast-to-coast ultramarathon spanning the length of the United States. The contest would soon be called the Bunion Derby in the press as runners faced grueling conditions running from Los Angeles to New York City.

An official 1928 poster of the Trans-Continental Foot Race, or Bunion Derby, sponsored by C.C. Pyle. (Source)

Also referred to as the Trans-America Footrace, the Bunion Derby covered 3,422 miles, following Route 66 from Los Angeles all the way to Chicago before finally ending in New York City. The first 10 winners would receive a cash prize, ranging from $25,000 to $2,500.

Edward Gardner’s wife, Mabel, encouraged him to compete in the endurance competition as means to support their family. Gardner recounted what she told him at the time: “All you’ve gotten out of your running up-to-date is a lot of loving cups [trophies]. Here’s a chance to get us what we need, so I guess you had better take a chance at this $25,000.”

With a wife and two young children to support, 30-year-old Gardner left for California to compete in a trans-continental ultramarathon with $175 to his name.

- More stories: John Mitchell Jr.’s Fight for Justice at The Richmond Planet

- More stories: Reckless Eyeballing: How Matt Ingram’s Story Reveals Fear of Black Sexuality

- More stories: The Fate of Margaret Morgan in Prigg v. Pennsylvania

Because Gardner did not own a car, he searched for someone nearby to drive him to Los Angeles. He eventually persuaded a middle-aged tailor named George Curtis to take him. Along the way, Curtis agreed to become Gardner’s running trainer for the duration of the Bunion Derby. He’d follow Gardner in his car along Route 66 and provide support as needed. Though Curtis had no training experience, Gardner agreed to share a cut of any winnings he might receive with his new running coach.

When the pair got to Los Angeles, Gardner officially entered the 1928 Trans-American Footrace. As Gardner trained for the ultramarathon in Los Angeles, a local professional boxing manager named Watson Burns was on the lookout for someone just like him. Burns wanted to sponsor one Black runner in the Bunion Derby in an effort to “encourage Black competition in all lines of sports.”

So when Gardner met Burns in early February, they agreed on a set of terms. Burns would pay for all of his expenses during the race in exchange for half of any prize money Gardner may win.

With his running team in place, Edward Gardner continued to prepare for a 3,400 mile race set to start the following month.

First Leg of the Derby

On March 4, 1928, 199 runners took off from Legion Ascot Speedway in Los Angeles as the Bunion Derby officially began. Including Gardner, five Black runners competed in the 1928 Trans-American Footrace. Most of the competitors had little to no experience running marathons, and a majority of the runners came from blue-collar backgrounds.

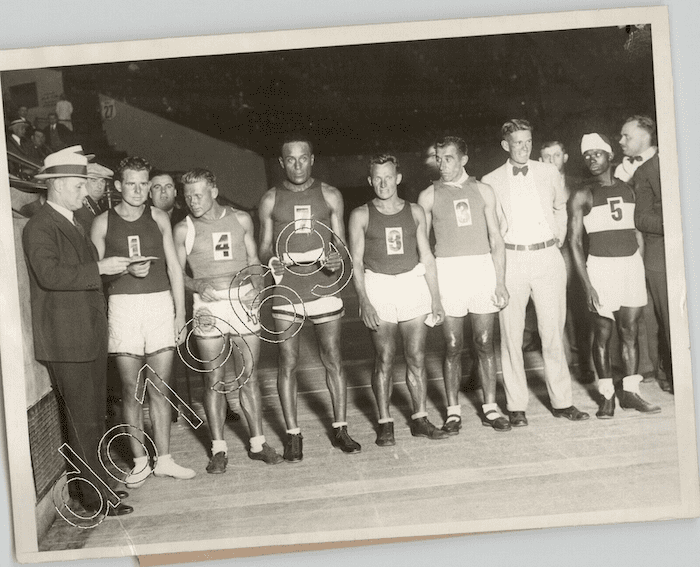

Runners gather at the starting line of the 1928 Trans-American Footrace in Los Angeles and wait for the race to start. (Source)

On the first day of the race, competitors ran 17 miles through heavy traffic as a parade of fans and admirers choked up the roadway. It’s estimated that more than 500,000 people lined up along the 17-mile-long road to Puente, CA.

The following day, Gardner and the other marathoners ran 34 miles in the rain. While resting at camp during the night, rain seeped through their tents. The exhausted men, many of whom nursed blisters and other injuries, were drenched. By the end of the second day, 183 runners remained in the Bunion Derby. Those who continued to run became known as “bunioneers” for their perseverance through painful foot and leg injuries during this grueling race.

To further add to their woes, runners faced inadequate accommodations and food. During a majority of the race, lunchtime meals consisted of only two jam sandwiches, coffee, and one orange. Runners’ health quickly deteriorated under these settings, but most of the men pressed on.

As they ran past the Mojave Desert from Victorville, some runners became badly sunburnt and dehydrated. Race organizers placed water stations between 5 and 15 miles apart, but it was far from enough. To make matters worse, one runner named John Stone described “stomach trouble, and other sickness” befalling some of his fellow runners, and suggested they were given unpurified water.

Regardless, Edward Gardner and 129 other men successfully crossed the Mojave Desert and remained in the race, averaging about 40 miles per day, every day.

Black Americans Follow Edward Gardner’s Progress

Nearly 300 miles into the Bunion Derby, Edward Gardner placed 3rd overall. He made headlines in two major Seattle newspapers, The Seattle Times and Seattle Post-Intelligencer, for his achievements. And as a result, his fan base grew more and more.

The Sheik was doing something incredible. By keeping pace with some of the best white long-distance runners in the country, Gardner was proving that Black people, too, can be exceptional athletes when given the opportunity.

Strange as it may seem today, many whites in the 1920s held onto a decades-old racist belief that white people were superior athletes to African Americans. But as Gardner continued to beat majority-white competitors in one of the most brutal and strenuous tests of endurance and strength, he was proving the racists wrong.

- More stories: Alvin “Shipwreck” Kelly & Flagpole Sitting in the 1920s

- More stories: How Enslaved Africans Hid Rice Seeds In Their Hair & Changed the World

- More stories: How a Retractable Syringe Exposed Powerful Group Purchasing Organizations

African American newspaper, California Eagle, offered to reward Gardner with a free trip to Los Angeles and a large sum of money if he won the ultramarathon. Owner of the newspaper, Charlotta Bass, viewed Gardner’s ongoing success in the race as an opportunity to push back against racist thinking surrounding Black athleticism.

Edward “Sheik” Gardner was becoming a symbol of promise to Black Angelenos as well. While competing in the Bunion Derby, he received offers for free services and gifts from Black business owners throughout Los Angeles, such as free real estate, free dental care, and even a job offer from a tobacco company. When running on sunny days, Gardner wore prescription sunglasses he received for free from a supportive Black ophthalmologist in the area.

Gardner Faces Jim Crow States During Ultramarathon

After braving the Mojave Desert, the Bunion Derby ultramarathoners next encountered high-altitude, mountainous running that cut past Flagstaff, AZ on Route 66. By the time the bunioneers cleared the mountains and entered New Mexico, Gardner was in 6th place.

As they continued running in the harsh desert environment, Gardner and the other runners confronted powerful sandstorms. In addition to the low visibility, 60 mph winds blew sand, rocks, and pebbles that cut into their skin. Gardner walked for hours during this storm, losing his way before finding Route 66 again.

Wearing number 165, Edward Gardner appears on camera before the start of the Bunion Derby on March 4, 1928. (Source)

When the ultramarathoners neared the Texas border, 94 men remained after the brutal tests from the previous 800 miles. In a positive shift, weather and terrain conditions improved for the Bunion Derby runners and provided some much-needed relief. But for the few Black runners in the race, deeply perilous circumstances awaited them as the pack crossed into Texas and entered Jim Crow country.

With Jim Crow as law of the land in many states, African Americans endured extreme racial discrimination and violence by the hands of white supremacists. Nearly every part of daily life was segregated, from transportation to entertainment, neighborhoods to schools.

During the 1920s, the KKK experienced a resurgence in membership as millions of men joined their ranks. Many members filled statewide and national elected positions, framing domestic policy for decades. All-white juries exonerated white men who murdered Black men, if the crime was ever even prosecuted in the first place.

As Edward Gardner pushed to make up ground he lost in the desert, he contended with a torrent of racist threats and attacks. He ran through “sundown towns” as white racists shouted racial epithets and threatened to physically harm him. Gardner in particular received a barrage of outrage and vitriol from angry white Southerners because he was the Black frontrunner who was beating out dozens of white athletes.

While resting for the night in McLean, Texas, a mob of angry white men surrounded Gardner’s tent and threatened to burn it down. Thankfully, he escaped the situation unscathed. On another day, a farmer riding a mule followed Gardner with a rifle pointed at his back for an entire day through western Oklahoma. He threatened to shoot him as soon as he passed a white runner. But Gardner pressed on, keeping as close to his usual pace as possible, though he was undoubtedly slowed by the barrage of racist attacks.

Despite the dangerous circumstance he faced, Gardner remained one of the top 10 runners of the Bunion Derby. He and the rest of the men were now running between 40 and 60 miles a day.

Difficult Conditions Runners Endured at the Bunion Derby

As the ultramarathoners continued running along Route 66, their sleeping arrangements deteriorated quickly. According to John Stone, who placed 33rd in the Trans-Continental Footrace, runners did not have their own bedding – each man received a different pillow and blanket every night.

“Our blankets and pillows were so filthy it was a disgrace to the race,” Stone said. In other words, when a man stepped on his pillow when getting ready in the morning, that same pillow carried the head of a different runner that night. When factoring in the notion that most men dealt with painful sores and other bloody injuries, it’s not hard to imagine the wretched state of those pillows and blankets.

- More stories: Esther Jones: Betty Boop’s Original Influence

- More stories: Yuri Kochiyama at Intersection of Black Power & Asian Movements

- More stories: When Martha Mitchell Was Right About Watergate

In defiance of these grotesque, even inhumane conditions, Edward Gardner and the remaining bunioneers pushed forward. They headed northeast toward Illinois on Route 66.

Unfortunately, C.C. Pyle added more pressure on the runners after they reached Chicago.The Trans-Continental Footrace was losing money, and he wanted the competition to end as rapidly as possible. So, he increased their daily mileage. For the last leg of the Bunion Derby, marathoners ran between 50 and 70 miles per day.

Gardner estimates he ran 84 miles on his longest day of the ultramarathon. Some runners did not reach camp until 2 or 3 in the morning, but still rose at sunrise to run again, every day.

Edward Gardner Finishes the 1928 Bunion Derby

As runners approached the East Coast, they could feel New York City was just on the horizon. After completing more than 70 miles a day for a spell, Gardner and the rest of the ultramarathoners appeared incredibly exhausted, even sickly. So in the final days of the Trans-America Footrace, race management drastically lowered daily mileage totals and allowed the runners to recuperate.

Runner Andy Payne won the 1928 Trans-Continental Footrace at 20 years old. (Source)

After 84 days and more than 3,400 miles, Edward “Sheik” Gardner and 54 other ultramarathoners finished the Bunion Derby in New York City on May 26, 1928. Gardner placed 8th overall and received $2,500. During the contest, he went through 14 pairs of shoes.

20-year-old Andy Payne from Oklahoma won the Bunion Derby and received $25,000. In addition to Gardner, two other Black runners finished the race, Tobie Cotton at 35th and Sammy Robinson at 45th.

With his share of the prize money he split with his trainer, George Curtis and business sponsor, Watson Burns, Gardner returned home to his wife and children in Seattle.

Gardner (#5) receives his prize along with other winners of the Bunion Derby (Source: Russell Iverson)

Second Bunion Derby & Gardner’s Final Races

Despite his successes, Gardner wasn’t quite finished with long-distance running competitions. Later in the year, Edward Gardner set the U.S. record for a 50-mile run by finishing in under 6.5 hours.

Undeterred by the grueling, difficult, and dangerous conditions he dealt with during the Bunion Derby, Gardner wanted another shot. He signed up for the second annual Trans-America Footrace in 1929 as the ultramarathon’s only Black competitor.

Joining 42 other veterans of the first Bunion Derby, Gardner and 35 other runners set off from New York City to Los Angeles in a reserved version of the course. Unfortunately, he suffered a leg injury and had no choice but to drop out in Oklahoma.

Recognizing what he meant to African Americans as the only Black man in the second Derby, he apologized profusely for being unable to finish it. “I wanted to keep on running and win—for you, my people,” Gardner said.

When the Great Depression hit, Gardner remained in Seattle and returned to work as a steam boiler repairman before eventually becoming a steel worker. After 1929, C.C. Pyle never hosted another Trans-American Footrace, and the time of the Bunion Derby came to end.

- More stories: The Lives of Ferguson & Black Lives Matter Activists Cut Short

- More stories: Why Zazu Nova’s Legacy at Stonewall Deserves More Recognition

- More stories: How Dr. Gertrude Curtis Broke Barriers as New York’s First Black Female Dentist

In 1938, Gardner won a 52-mile-long walking competition around Lake Washington and beat the course’s previous record. However, it was the last endurance competition he won.

His wife, Mabel, died in 1960, and Gardner carried on working as a school janitor in North Seattle until he died of a stroke in 1968 at 70 years old.

Edward Gardner became a national symbol of Black excellence in the aftermath of the Bunion Derby. His ability to stay cool and focused as racist whites hurled death threats and insults at him in the Jim Crow South made him a hero to much of the Black community who closely followed his progress in the Trans-American Footrace. Furthermore, he provided hope for millions of African Americans as he defied racist stereotypes and proved that Black athletes deserve equal opportunity to achieve something extraordinary.

If the Sheik could make it happen, why couldn’t they?

For an engaging retelling of Eddie Gardner’s journey during the Bunion Derbies, check out Charles Kastner’s book, “Race across America: Eddie Gardner and the Great Bunion Derbies.”

Shari Rose,

As a young kid I knew Ed Shiek Gardner. He worked and lived at the Blessed Sacrament Catholic Church Prior from about 1961 to close to the time of his death. He had a very interesting artistic skill. Charles Kastner researched his life for 8 years I have read. Know where to contact him?

If you want information, happy to talk, in fact want to preserve the history I know of him. Do you know where his family is?

Hi Fred – thank you so much for reaching out. This story about Edward Gardner was one of my all-time favorites to write, and I’d love to learn more about him and potentially add more details about his life to this piece. Please feel free to email me at [email protected] and we can discuss further. Thanks again!