Yuri Kochiyama at Intersection of Black Power & Asian Movements

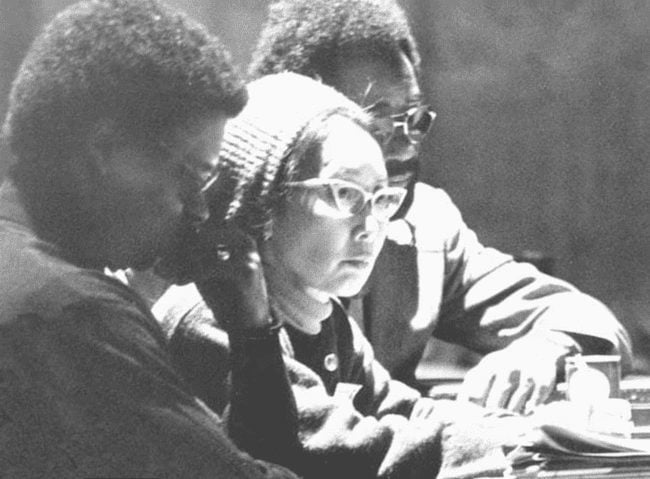

Yuri Kochiyama in Harlem. (Source)

January 27, 2022 ~ By Shari Rose

Yuri Kochiyama’s activism in Harlem and her friendship with Malcolm X laid the foundation for a lifelong activist

On May 19, 1921, Mary Yuri (Nakahara) Kochiyama was born in San Pedro, CA. Her father, Seiichi Nakahara, owned a fish and marine supply business, and her mother, Tsuma Tsuyako Nakahara, was a piano teacher. Yuri and her two brothers were second-generation Japanese Americans, known as Nisei in Japanese.

As a child, she often shirked her household chores and opted for extracurricular activities and leadership positions. Yuri attended San Pedro High School and became the school’s first female vice president. An avid tennis player as a teenager, she wrote about sports for the San Pedro News-Pilot. In 1939, Yuri graduated high school and spent two years at Compton Junior College, where she majored in Journalism and English. In her free time, she taught Sunday school to a class of mostly white students.

Yuri Kochiyama had just returned home from teaching when her father was arrested by the FBI on December 7, 1941.

Detainment At Japanese Internment Camp

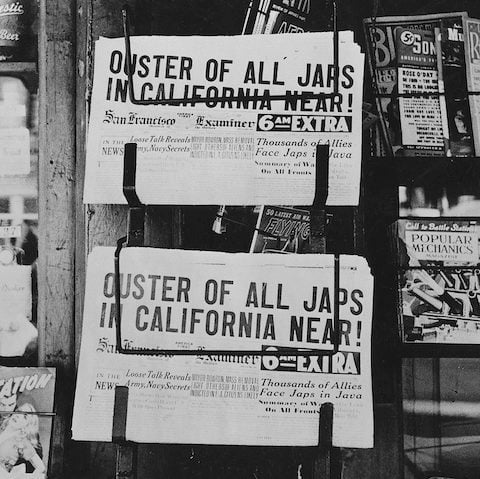

Kochiyama’s father is widely believed to be one of the first Japanese Americans arrested in the immediate aftermath of the Pearl Harbor bombing in Hawaii. The FBI accused Seiichi Nakahara of espionage against the United States, and took him to prison under President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066. Kochiyama spoke with the FBI agents in her home before he was arrested:

A February 1942 newspaper headline from the San Francisco Examiner about the internment of Japanese Americans. (Source)

“And they said, ‘Well, where is he?’ And I pointed to one of the bedrooms. And they went in and got — it was done so quickly, it didn’t even take a half of a minute, I don’t think. And I didn’t dare ask a question. They were going out the door immediately. And then, I just called my mother, who was right down the street, to say, ‘Come home quick. The FBI just came and took pop.’”

Her father had recently undergone ulcer surgery and just returned home to recover when he was incarcerated. Nakahara was denied medical care while in federal custody and died a month and half later.

Kochiyama and the rest of her family members were later detained and sent to a Japanese internment camp in Jerome, Arkansas. While in detention for over two years, she taught Sunday school at the camp and embarked on a letter writing campaign to Japanese American soldiers serving in World War II. These efforts were so successful that they became public outside the camp, and she published the soldiers’ responses in her newspaper column titled, “Nisei in Khaki.”

Kochiyama Meets Her Husband & Moves to New York

Yuri Kochiyama was released from the internment camp in 1944 and chose to work for a USO center in Mississippi that supported soldiers coming back from the war. While working there, she met Bill Kochiyama, a private from the 442nd Regimental Combat team. The 442nd was a highly decorated group composed of mostly Japanese American soldiers.

Yuri and Bill married in 1946 and moved to New York City. The couple was deeply involved with community service, and worked to support Japanese and Chinese American soldiers as they headed off to fight in the Korean War. Even as they grew their family, they hosted many AAPI-centered occasions at their home, and always had people over.

Yuri Kochiyama with five of her children. (Source)

While living in New York, the 442nd organized events in the U.S. for Japanese survivors of the Hiroshima bombing. Known as the Hiroshima Maidens, or hibakusha, this group of two dozen women were teenagers when the United States dropped the atomic bomb. As a result, they suffered horrific radiation burns to their arms and faces, and were left with permanent physical deformities. Because advancements in plastic surgery in the U.S. outpaced that of Japan, they came to New York for different operations.

Yuri Kochiyama was pregnant with her fourth child when she met with the Hiroshima Maidens in the mid 1950s. Serving as an ambassador of sorts, Kochiyama helped facilitate different activities for the Maidens, such as dances and dinners. She said, “Though all us wives also attended the dance, the 442nd men danced only with the Hiroshima Maidens. The Maidens were made to feel really special.”

- More stories: Masako Katsura: Japanese Billiards Player Who Broke Gender Barrier

- More stories: How Journalist Ruben Salazar Gave Voice to Chicanos in Los Angeles

- More stories: Israel Has Killed a Record Number of Journalists & Aid Workers in 6 Months

The Kochiyamas Move to Harlem

In 1960, Yuri and Bill moved their family to Harlem. At that time, the median income of central Harlem was 60% of New York City’s median as most residents worked low-paying jobs. The infant mortality rate in Harlem was double the city’s average.

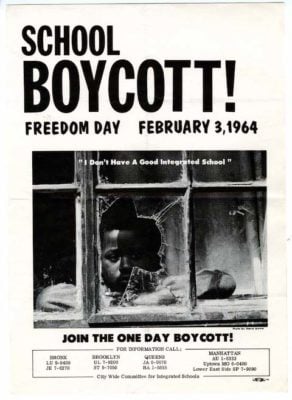

Flyer for a school boycott in New York City on February 3, 1964. (Source)

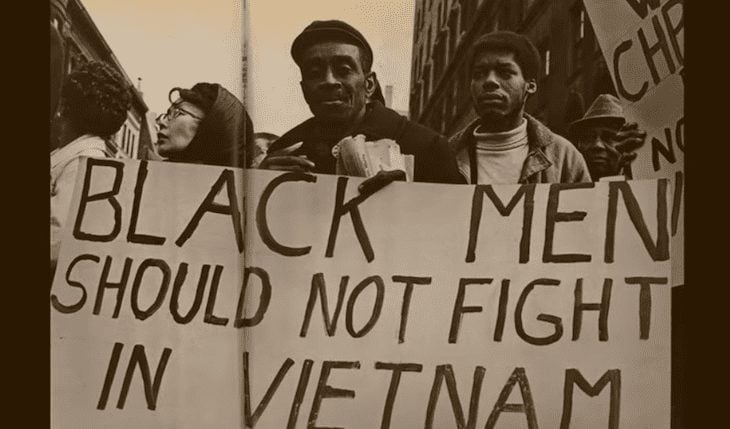

In the early 1960s, Harlem was an epicenter of social justice movements as Black and Latino residents fought to secure a better life in their neighborhoods. Massive labor strikes, school boycotts, protests against police killings and the Vietnam War were part of the fabric of the area. The Civil Rights Movement and Black Power Movement had caught fire, and Yuri Kochiyama soon got involved.

In the summer of 1963, new construction on the Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn promised to offer crucial jobs to local residents. However, the construction company refused to hire Black and Puerto Rican workers, opting instead for a nearly all-white workforce. So, a group called CORE, or Congress of Racial Equality, started organizing sit-ins, protests, and demonstrations to challenge flagrant job discrimination.

Kochiyama joined CORE in performing daily sit-ins at the construction site, and got her first taste of the power that civil disobedience provides. CORE blocked trucks from entering zones, slowed the transport of raw materials, and ultimately halted production. Her oldest son, 16-year-old Billy, joined her in these demonstrations, alongside Black and Puerto Rican protesters.

CORE protesters sit on construction equipment in Brooklyn as police arrest them in 1963. (Source)

An estimated 650 people were arrested during those protests, including Yuri and her son. Kochiyama said of her arrest, “Everybody was getting arrested. It was no big thing. Everybody was taking turns.”

- More stories: ‘Reckless Eyeballing’ and the Fear of Black Male Sexuality During Jim Crow

- More stories: Wheelchairs & Airlines: Why Is Flying So Risky for Those With Disabilities?

Yuri Kochiyama Meets Malcolm X

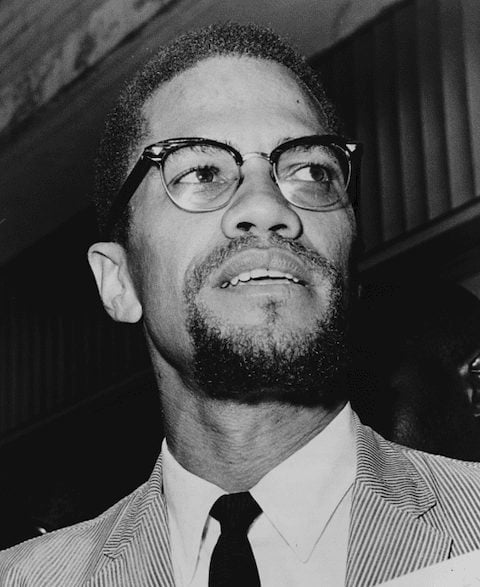

On October 16, 1963, Kochiyama appeared in a Brooklyn courthouse for her hearing, along with other demonstrators arrested over the summer. She was shocked to find someone she recognized in the courtroom’s gallery. Malcolm X was present, surrounded by a group of young Black activists eager to speak with him.

Malcolm X in 1964. (Source)

Kochiyama eventually summoned the courage to introduce herself to Malcolm X:

“I felt funny, but I slowly moved closer and closer to where Malcolm and all his admirers were standing. I remained a little on the outside to give Blacks the privacy they deserved. All of a sudden there was a window of opportunity – Malcolm looked up and seemed to be looking right at me. He was probably wondering, ‘Who’s this old lady, and Asian at that?’ I stepped forward and called out, ‘Can I shake your hand?’ He looked at me and demanded, ‘What for?’ I stammered back, ‘I want to congratulate you.’ And he asked, ‘For what?’ I was trying to think of what to say and said, ‘For what you’re doing for your people.’ ‘What’s that?’ he queried. ‘For giving them direction.’ He abruptly burst forth with that fantastic Malcolm smile and extended his hand. I grabbed it. I could hardly believe I was actually meeting the Malcolm X.”

Kochiyama’s meeting with Malcolm in Brooklyn formed the beginning of a friendship that lasted until his assassination.

Hiroshima-Nagasaki World Peace Mission Study

Several months after meeting Malcolm X, Kochiyama received a letter from a peace organization that sought to connect her with a group of hibakusha survivors and journalists. The group also specifically requested that Malcolm X attend as well, if possible. Kochiyama agreed to host the bombing survivors at her home, and reached out to Malcolm’s office. They replied he would try to attend, but made no promises.

The Hiroshima-Nagasaki World Peace Mission Study was composed of a group of 25 survivors of the two atomic bomings in Japan. They visited more than 100 cities throughout the U.S., Europe, and Soviet Union to speak about their experiences and injuries, as well as call for the abolition of war.

Kochiyama stands with Black activists in New York City. (Source)

On June 6, 1964, they visited the home of Yuri Kochiyama in Harlem. And to everyone’s surprise, Malcolm X arrived at her home, too. Kochiyama spoke about his visit with the Japanese survivors:

“His appearance electrified the room. But our guests were also apprehensive: Would he be hostile to such an integrated audience? Would he treat the whites poorly? He was nothing the people expected. There was no arrogance, no egocentricity, no hostility; instead he was gracious, warm, personable. We all noticed that he was as friendly to whites as to Blacks. He shook hands with everyone within reach.”

Kochiyama said that Malcolm spoke to the survivors, and related their experiences to the experiences of Black Americans:

“‘You were bombed and have physical scars,’” Malcolm said. “We too have been bombed and you saw some of the scars in our neighborhood. We are constantly hit by the bombs of racism.’”

In a 2008 interview, Kochiyama spoke about what it meant to have Malcolm X at the event. “Well, we were all so happy, I mean, especially Japanese Americans and even other Asian Americans, that Malcolm would be interested. But Malcolm was interested in every group, and especially when he would hear the kind of harassment and all the negative things that always seemed to be happening to people of color. And he knew about Asian history so well. We couldn’t believe it.”

- More stories: California’s History of Anti-Asian Laws and Riots

- More stories: The Lives of Ferguson & BLM Activists Cut Short

Kochiyama at the Intersection of Black Power and Asian American Movements

Yuri Kochiyama and some of her older children continued to attend talks hosted by Malcolm X and his associates. In November 1964, he invited Kochiyama to visit his OAAU Liberation School in Harlem.

The Organization of Afro-American Unity was a Pan-Africanist institution founded by Malcolm X earlier that year. The school sought to promote the civil rights of Black Americans as well as draw connections from their fight for equality to the struggle of Africans throughout the world. The histories of imperialism, slavery, capitalism, and how those forces persist today were some of the major themes taught at the Harlem Freedom School that Kochiyama attended.

Kochiyama wears her trademark cat eye glasses at a New York City protest. (Source)

The following month, Kochiyama attended her first class. According to her notes, she learned about the history of 20th century slavery, colorism, and the continuation of the lord-serf relationship into the modern day. She found particular interest in imperialism and colonialism in Africa, and soon made connections to the racism and violence leveled upon Black Americans she witnessed in her neighborhood.

“Malcolm wanted to make things better for his people, and he saw racism and imperialism as the cause of these problems and the solution must be international,” she said. “It was these revolutionary ideas that I was attracted to, though I didn’t know much about them at the time.”

Kochiyama gives a speech at an anti-war protest in Central Park in 1968. (Source)

Despite being the only non-Black person in class, Kochiyama began to form relationships with teachers and other students. She attended every Saturday class until the school shut down in spring 1965. She left with a deeper understanding of both African and Asian history, and how similarities could be found across their histories. She also had a better understanding of the context with which Malcolm X spoke and taught others:

“One of the greatest lessons Malcolm taught people was to learn their own history,” she said. “Know your history. Know the world. Be proud of who you are … Through the process of discovering our own histories, many peoples – Africans, Asians, Puerto Ricans living in the United States – learned how to throw off our internalized racism and develop pride in our heritage. But don’t stop there. Learn about the histories of other people. And learn about the history of social movements because this is how you learn to create social change.”

Yuri Kochiyama at the Assassination of Malcolm X

On February 21, 1965, Kochiyama and her oldest son, Billy, sat in the audience of the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem to listen to Malcolm X speak. One of his associates, Benjamin Karim had finished speaking, and introduced Malcolm to the stage.

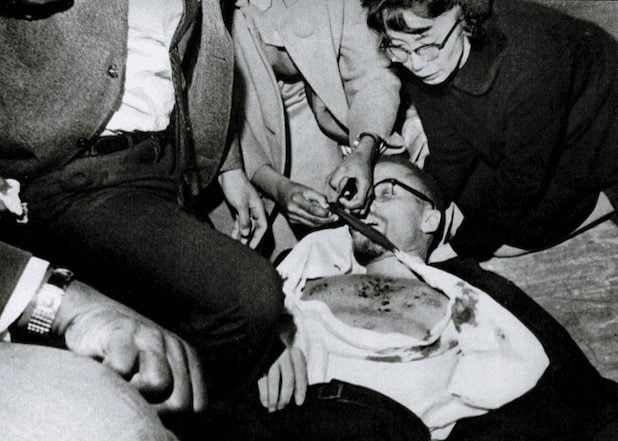

As Malcolm X stood in front of the audience, a man in the crowd began yelling, creating a diversion. Malcolm called for calm, saying, “Cool it, brothers, cool it.” But, multiple men in the audience then ran to the front and shot him several times. He fell backward.

Kochiyama rose from her seat and ran onstage with a handful of others in attendance. She reached him as he struggled to breathe.

“[Malcolm] was having trouble breathing, so I put his head on my lap,” she said. “Others came and opened his shirt. He was shot so many times in the chest. And by his jawbone and his finger. I hoped he would say something, but he never said a word.”

Yuri Kochiyama cradles Malcolm X’s head after he is shot at the Audubon Ballroom on February 21, 1965. (Source)

Malcolm X was pronounced dead soon after arriving at a Washington Heights hospital at the age of 39.

Continued Activism in Harlem

After Malcolm X’s death, Kochiyama pushed forward with her activism. She became a well-regarded leader of the Asian American movement in the late 1960s, and continued to draw connections between the Black liberation movement and Asian American rights. Her speeches covered a wide range of topics, from anti-imperialism to interracial solidarity, Maoism, and Black nationalism. Among contemporary Black activists, she was known as “Sister Yuri.”

Additionally, Kochiyama fought for the rights of political prisoners and incarcerated activists, criticizing America’s prison system and relating it to her own detainment during World War II. She joined protests against the Vietnam War and was arrested alongside Puerto Rican demonstrators at the Statue of Liberty in the late 1970s.

Yuri Kochiyama walks with other demonstrators at a New York City protest against the Vietnam War. (Source)

In the 1980s, Yuri Kochiyama and her husband, Bill, joined the East Coast Japanese Americans for Redress to secure reparations from the U.S. government with regard to internment camps. After decades of fighting for not only the acknowledgement of race-based mass incarceration and exclusion, but also redress compensation, it was finally granted. More than 82,000 surviving detainees were paid $20,000 each in the 1990s, fifty years after their internment.

Kochiyama was also heavily engaged with the campaign to save Mumia Abu-Jamal, a Black nationalist who was given the death penalty after the 1981 shooting death of a Philadelphia police officer. She was a member of the New York Coalition to Free Mumia Abu-Jamal as well as the Asian Ad Hoc Committee for Mumia. Abu-Jamal’s death sentence was eventually dropped in 2011, but he will spend the rest of his life in prison.

- More stories: The Anti-Filipino Watsonville Riots of 1930

- More stories: El Negro Matapacos & the Riot Dogs Who Protect Protesters

Kochiyama’s Final Years

Bill Kochiyama died in 1993. After having a stroke in 1999, Kochiyama moved to Oakland, CA to be closer to her family. She spent her final years pursuing activism in California. In 2003, Kochiyama did an extensive interview with the Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors at the age of 82.

Yuri Kochiyama gives a speech in Oakland in 2002. (Source)

She spoke at length about the treatment of Muslims in the U.S. after 9/11, and drew connections with the treatment of Japanese Americans after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

“There is only one super-power, the United States,” she said. “To make or bring on wars, wars begin with greed for land or resources, lies and demonizing the target, and controlling one’s own homeland with harsh measures or restrictions. Today, there’s no concentration camp or internment camps like the Japanese experienced, but the Arabs, Muslims, and South Asians are the new targets. They are losing jobs, homes, and even their lives.”

Controversially, Kochiyama said in this interview that she considers Osama bin Laden to be a person she admires:

“To me, [bin Laden] is in the category of Malcolm X, Che Guevara, Patrice Lumumba, Fidel Castro, all leaders that I admire. They had much in common. Besides being strong leaders who brought consciousness to their people, they all had severe dislike for the U.S. government and those who held power in the U.S..”

She continued: “And today, when I think what the U.S. military is doing, brazenly bombing country after country, to take oil resources, bringing about coups, assassinating leaders of other countries, and pitting neighbor nations against each other, and demonizing anyone who disagrees with U.S. policy, and detaining and deporting countless immigrants from all over the world, I thank Islam for bin Laden,” she said. “America’s greed, aggressiveness, and self-righteous arrogance must be stopped. War and weaponry must be abolished.”

In 2005, Kochiyama was one of the women nominated for the “1,000 Women for the Nobel Peace Prize.” Additionally, a band named the Blue Scholars released a song called “Yuri Kochiyama” in 2011. It contains lyrics such as “Cause when I grow up, I wanna be just like Yuri Kochiyama / Imma serve the people proper / When I grow up, I wanna be like Yuri Kochiyama.”

Kochiyama speaks in an interview in 2009. (Source)

On June 1, 2014, Yuri Kochiyama died at the age of 93. She received accolades from AAPI- and Black-led associations, progressive organizations, and other groups. A few days after her death, the California State Assembly adjourned in her memory. The Obama administration released a statement, saying in part, “Yuri leaves behind a legacy of courage and strength, and her lifelong passion for justice and dedication to civil rights continue to inspire young AAPI advocates today.”

0 Comments